Why Do Corporations Merge and Why Should Law Care?

Abstract

Mergers and acquisitions are extraordinarily prevalent in the United States, generating massive expenditures every year. However, a serious empirical puzzle lies at the heart of all that activity. That empirical phenomenon’s most remarkable feature by far is that even though it is well established in an extensive literature and implies far-reaching policy consequences, American law ignores it entirely.

Generations of researchers have failed to find evidence that merger and acquisition activity generates any lasting benefits for the combining firms’ owners or anyone else. No one seriously doubts that efficiencies of scale or technological integration are real or that acquisitions sometimes achieve them. Still, the evidence strongly implies that they are mostly available in small deals among small firms. While the results are no longer very seriously contested, no one has any conclusive explanation for the several puzzles they pose.

This paper comprehensively reviews the empirical literature and works through the policy implications for the major bodies of law it affects. The most important insights are two. First, the evidence should undermine the confidence among scholars of corporation law in the regulatory self-sufficiency of market institutions, on which corporation theory depends so heavily. In particular, a major hope for controlling managerial agency cost—one of the theory’s chief preoccupations—remains the hope that the so-called “market for corporate control” governing hostile takeovers will discipline underperforming managers. The evidence discussed here suggests that the market produces no meaningful benefits at all. The second lesson is simpler. The other major legal regime governing mergers and acquisitions—antitrust—should return to the simpler, pro-enforcement presumptions by which it once more effectively limited market concentration. The fear of jeopardizing pro-competitive gains, on which antitrust merger law has been rendered largely inert, is no longer very defensible. The balance between false positive and false negative should be reset.

Why Do Corporations Merge and Why Should Law Care?

Merger and acquisition activity is an extremely busy engine in the U.S. economy. At its heart, however, lies a serious empirical puzzle. It remains not only unsolved but largely ignored, and it reflects an incoherence throughout much of American business-regulatory policy and its theoretical foundations.

Namely, though corporate combinations are hugely common and have been for over a century, a large body of empirical evidence now suggests that they do not do any good for the combining firms’ owners or anyone else. While the problem is not unknown among academics and the result is no longer very seriously doubted, no one has any good explanation for it.

Not only do corporate managers continue in this apparent omnipresent irrationality, but they spend massive amounts of money on it.1Total annual value of deals in most recent years has met or exceeded trillion, and

the record for annual value was recently set at nearly trillion. Overall value since 2013 is well

over trillion. See Deloitte, The State of the Deal: M&A Trends 2020, at 2, 5 (2020), https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/mergers-acqisitions/us-mna-trends-2020-report.pdf; Stephen Grocer, A Record .5 Trillion in Mergers Were Announced in the First Half of 2018, N.Y. Times, (July 3, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/03/business/dealbook/mergers-record-levels.html [https://perma.cc/2EF9-TS2N]; Bourree Lam, 2015: A Merger Bonanza, The Atlantic (Jan. 9, 2016), https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2016/01/2015-mergers-acquisitions/423096/ [https://perma.cc/V874-FF2P]. The annual record was set at nearly trillion in 2021. Michelle F Davis, Bankers Weigh What’s Next After Historic Trillion M&A Record, Bloomberg (Dec. 28, 2021) https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-12-28/bankers-weigh-what-s-next-after-historic-5-trillion-m-a-record#:~:text=Companies%20announced%20a%20mammoth%20%245,right%20up%20until%20the%20holidays. Most remarkable—and a fact that will turn out to be significant in this study—is that acquiring firms pay large “premiums” for their targets. A takeover proponent ordinarily must spend substantially more for a controlling percentage of shares in a target firm than the shares’ current trading price.2In some years the average premium in excess of the target firms’ pre-acquisition share prices has been as much as 50%, and premiums in individual deals sometimes more than double it. See, e.g., Bubble Stocks Top the Takeover Premium Charts, Seeking Alpha (Sept. 23, 2016), https://seekingalpha.com/article/4008095-bubble-stocks-top-takeover-premium-charts [https://perma.cc/5H6E-ZDAL]. Assuming that large premiums reflect rational estimates of cost-saving synergies, pricing power, or some other advantage that will come from a merger, they imply very large gains, either for shareholders or society, or both. Based on that reasoning, merger premia under current circumstances would indicate that acquisitions contribute more than $300 billion in shareholder or social gains per year, an amount that would represent a non-trivial fraction of the entire U.S. GDP.3Takeover premiums currently average well over 30%, and annual total deal value has been running at about trillion. Jens Kengelbach & Alexander Roos, Boston Consulting Group, Riding the Next Wave in M&A 10 (2011) https://www.bcg.com/publications/2011/riding-the-next-wave-in-m-and-a [https://perma.cc/EMR3-PLQV] (finding average premium of 36% from 1990 to 2010, with annual peaks as high as 45%). Therefore, aggregate merger premiums in recent years have been about 0 billion.

But therein lies the empirical puzzle. Over several decades of research, the dozens of researchers who have looked for those gains have been unable to find any meaningful evidence of them at all. Even the large premium payments enjoyed by target-firm shareholders represent merely a one-way wealth transfer from acquiring-firm shareholders. And aside from that one-time payday, the empirical evidence strongly suggests that growth by acquisition, on average, causes both acquiring and target firms to lose value or break even at best, generating no demonstrable benefit to anyone else. No one seriously doubts that efficiencies of scale or technological integration are real or that acquisitions can achieve them. Still, the evidence strongly implies that these benefits are mostly available only in small deals among small firms. The only deals relevant to important policy issues are very large in relative terms—that is, deals are typically policy-significant only when they are between firms that hold substantial market shares in concentrated markets. Surprising as these results may seem, they just confirm with empirical rigor what was already longstanding Wall Street wisdom: most deals fail, and they fail with capricious unpredictability.4See, e.g., Andrew Ross Sorkin, Is Merger Advice Worth the Price?, N.Y. Times (Aug. 6, 2007), https://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/06/business/worldbusiness/06iht-banker.4.7004868.html [https://perma.cc/EE2Y-JK9W] (referring to “[t]he old adage that half of all deals destroy value”); see also The Trouble With Mergers, Cont’d, The Economist, Nov. 28, 1998, at 15 (noting academic consensus that acquiring firms lose value, apparently because efficiencies prove elusive). As many as 70% of acquisitions are said to fail on some measure,5Clayton M. Christensen, Richard Alton, Curtis Rising & Andrew Waldeck, The New M&A Playbook, Harv. Bus. Rev., Mar. 2011, at 49. and easily a third or more fail in the ultimate sense that the acquired assets are later resold.6See, e.g., David J. Ravenscraft & F.M. Scherer, Mergers, Sell-Offs, and Economic Efficiency 1–2, 159–65 (1987) (finding divestiture to follow from as much as a third or more of mergers); Michael E. Porter, From Competitive Advantage to Corporate Strategy, Harv. Bus. Rev., May 1987, at 43, 46 (finding that among a sample of large firms as many as 50% of assets acquired in conglomerate merger wave of 1960s were later divested); see also Steven N. Kaplan & Michael S. Weisbach, The Success of Acquisitions: Evidence from Divestitures, 47 J. Fin. 107, 107 (1992) (finding that in a large sample of mergers, 44% of acquired assets were divested, but arguing that not all divestitures are evidence of failure).

These results are starkly at odds with presumptions underlying American business regulation and its theory. Leading theoretical models in law, finance, and economics presume the rationality of business firms and thus take for granted that mergers and acquisitions create value for someone.7Firm-level rationality— the idea that firms make decisions to maximize the stream of profits owned by the firm, regardless what might be the individual interests of its managers or other stakeholders—is presumed from the simplest microeconomics, see Dennis W. Carlton & Jeffrey M. Perloff, Modern Industrial Organization 35–78 (4th ed. 2015), to the most sophisticated formal models of merger behavior, see Joseph Farrell & Carl Shapiro, Horizontal Mergers: An Equilibrium Analysis, 80 Am. Econ. Rev. 107, 110 (1990) (influential merger model of substantial mathematical complexity, assuming that firms “maximize . . . profits”). Otherwise, the thinking goes, rational firms would not pursue them. It is lost on no one that executives might disserve their shareholders through selfishness or incompetence—this is the problem known as “agency cost” and it is taken as uncontroversial in corporate theory.8This problem of agency cost is often described as “[a] core problem—if not the problem” in corporation theory, Kobi Kastiel & Yaron Nili, Competing for Votes, 10 Harv. Bus. L. Rev. 287, 293 (2020), and it has been at least since the seminal Michael Jensen & William Meckling, Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Capital Structure, 3 J. Fin. Econ. 305 (1976). The roots of the idea are older yet. Robin Marris captures what has been, since Adolf Berle & Gardiner Means, The Modern Corporation and Private Property (1932), a standard consensus: “Under any conditions of less than perfect competition, profit maximization is rarely compulsory, and when the decision-taker is not directly the profit-receiver, profits need not necessarily represent even one dimension of motivation.” Robin Marris, A Model of the “Managerial” Enterprise, 77 Q.J. Econ. 185, 186 (1963). However, it is widely presumed that market forces control that behavior pretty well, especially when companies adopt governance tweaks recommended in the academic literature of the day.9Within the massive literature on agency costs produced since Jensen & Meckling, supra note 8, there is a predominant view that favors reliance on market forces to align management and shareholder interests, as opposed to regulatory intervention or liability rules. Any number of specific market-oriented solutions have been suggested. The most prominent proposal happens to be one that is central to this paper: that hostile takeovers should be encouraged, so that society benefits from the so-called “market for corporate control.” If incumbent managers know their firms can be taken from them when they underperform (and their stock prices therefore fall, making hostile takeover a bargain), they will work to keep share prices high. See discussion infra Part II.C. Other proposals include many variations on shareholder empowerment or institutional investor oversight, meant to tie shareholder self-interest more meaningfully to long-term corporate performance, see, e.g., William W. Bratton & Michael L. Wachter, The Case Against Shareholder Empowerment, 158 U. Pa. L. Rev. 653, 655–659 (2010) (describing some such proposals), steps to make proxy contests more like competitive markets, Kastiel & Nili, supra note 9, at 293, and executive compensation designs that align managers’ personal interests with share performance. Kevin J. Murphy, Executive Compensation: Where We Are, and How We Got There, in Handbook Of The Economics Of Finance 211 (George Constantinides et al. eds., 2013). Interestingly, one very well-known suggestion is to make corporate governance better by using market forces to shrink the amount of government regulation itself. Roberta Romano, Empowering Investors: A Market Approach to Securities Regulation, 107 Yale L.J. 2359, 2361 (1998), recommends that firms be allowed to choose whether to be subject to federal or state securities regulation, and predicts that competition among regulatory regimes would result in an optimal amount of regulation. One imagines that it would result in much less regulation, and so a market solution would lead to more reliance on market institutions. Thus while corporate, securities, antitrust, and some other bodies of law oversee merger conduct, they each do so only nominally and, on the presumption of that conduct’s rationality, wind up leaving it effectively unregulated. Admittedly, these laws’ combined effect is a very expensive compliance obligation, and no doubt merging parties and their lawyers would be amused to hear that their deals are “unregulated.” But indeed, the whole regulatory edifice rarely stops or seriously limits their ability to merge. It merely imposes costs.

Certain puzzles remain unexplained. Above all, if mergers really do no good even for the merging firms’ shareholders, some explanation is needed for why their managers would still seek them out. That puzzle has been a preoccupation of management scholars and economists for a generation or more.10See, e.g., Yaakov Weber, Shlomo Yedidia Tarba & Ziva Rozen Bachar, Mergers and Acquisitions Performance Paradox: The Mediating Role of Integration Approach, 5 Eur. J. Int’l Mgt. 373 (2011); see generally discussion infra Part IV.A.1. A separate puzzle stems from the presumption that mergers are at least sometimes anti-competitive. There is an assumption that some mergers create profitable market power by reducing the number of competitors in a market and empowering those that remain to raise their prices. The whole antitrust law of merger and acquisition is predicated on that assumption. The mechanisms by which anti-competitive effects could occur are well understood,11See infra notes 107–09 and accompanying text. and evidence of it happening has recently grown.12See generally Jonathan B. Baker, The Antitrust Paradigm (2019) (reviewing recent literature). But it remains a mystery how mergers could generate market power, enabling supra-competitive prices, without systematically benefitting shareholders. If mergers give firms market power, why do firms struggle to make money from them?

While dozens of explanations have been offered for the empirical mysteries surrounding mergers and acquisitions, many can be rejected. The best-supported explanation is that large-firm managers are comparatively free from shareholder interests. In other words, the explanation for merger riddles that best fits the evidence turns out to be the familiar problem of agency cost. Managers can make decisions to some degree for their own reasons. In fact, empirical “puzzles” of this kind are common throughout corporate governance and economic regulation. They often seem puzzling only because of strong assumptions, like firm-level rationality or the strength of market institutions that will keep firms rational. That same slippage of incentives probably explains counter-intuitive trends like the seemingly counterproductive design of governance institutions,13Specifically, on the advice of academics and management advisers, corporations have widely adopted governance innovations that have been shown to be ineffective, and sometimes even harmful. Prominent examples are “board independence” reforms, see Urska Velikonja, The Political Economy of Board Independence, 92 N.C. L. Rev. 855, 858 & nn.7–8, 863–73 (2014) (documenting extensive adoption of board independence reforms and evidence that they have often been irrelevant or even harmful); Sanjai Bhagat & Bernard Black, The Uncertain Relationship Between Board Composition and Firm Performance, 54 Bus. Law. 921, 942 (1999) (evidence that board independence does little or no good); Usha Rodrigues, The Fetishization of Independence, 33 J. Corp. L. 447, 452 (2008) (same); Paul Rose, The Corporate Governance Industry, 32 J. Corp. L. 887, 909–15 (2007) (same), and efforts to involve institutional investors, see Ronald J. Gilson & Jeffrey N. Gordon, The Agency Costs of Agency Capitalism: Activist Investors and the Revaluation of Governance Rights, 113 Colum. L. Rev. 863, 889–95 (2013) (explaining how the rise of institutional investors might just replace traditional agency costs with new and different agency costs); K.J. Martijn Cremers & Simone M. Sepe, Institutional Investors, Corporate Governance, and Firm Value, 41 Seattle U. L. Rev. 387, 394 (2018) (noting the general underperformance of institutional investors as governance constraints); Mark R. DesJardine & Rodolphe Durand, Disentangling the Effects of Hedge Fund Activism on Firm Financial and Social Performance, 41 Strat. Mgt. J. 1054, 1078 (2020) (finding large short-term gains in targeted firms’ financial performance followed by substantial long-term declines). excessive executive compensation,14See generally Kevin J. Murphy, Executive Compensation: Where We Are, and How We Got There, in 2 Handbook Of The Economics Of Finance 211 (George Constantinides et al. eds., 2013) (canvassing background and evidence of incentive compensation). and the widespread pursuit of celebrity CEOs.15See generally Jonathan A. Knee, Bruce C. Greenwald & Ava Seave, The Curse of the Mogul: What’s Wrong with the World’s Leading Media Companies (2d ed. 2011) (presenting empirical evidence that pursuit of high profile, empire-building CEOs has been bad for media companies, which nonetheless continue systematically to pursue them). There is no need to believe in systematic irrationality or failed economic theory to explain these things if market institutions do not work very well to control managerial opportunism, slack, or incompetence. This Article’s concluding section will offer ideas for retooling policy without making such presumptions.

This Article comprehensively reviews the empirical literature and the several confusing puzzles it raises and works through the policy implications for the bodies of law it affects. It begins by briefly recounting the histories of American merger activity and merger regulation, both of which disclose a key theme. Popular concern over rapid consolidation drove periodic reform efforts that sought to control it, but in every case the reforms were ineffective because enforcement proved politically costly. The Article then briefly reviews the theoretical foundation on which merger activity has been justified. That is, it considers the body of economic theory that has mostly persuaded American policymakers to leave merger activity alone, the central thrust of which has always been theoretical arguments that business activity must be rational and, therefore, beneficial. That review is important in understanding the popular and government ambivalence that frustrates enforcement and in judging the policy recommendations that will be made here. The Article then turns to the heart of its study, the empirical mergers and acquisitions literature and the several puzzles it raises. It concludes by working out some implications for the legal rules that mostly deal with acquisitions: the law of corporations, securities, and antitrust.

These policy lessons are not extensive or revolutionary and they are secondary to the Article’s main focus, which is on the empirical puzzle. But they are nevertheless fundamental. The lesson for corporate and securities law is simply that market institutions cannot constrain managerial agency costs in the way the literature has overwhelmingly presumed. The literature’s key remedy for agency costs remains the market for corporate control, and many scholars cling to a commitment that it can outperform legislation or judicial intervention. But that market institution depends on an efficient world of hostile takeover that the empirical evidence discredits entirely.

As for antitrust merger law, there is no longer any compelling reason for the caution by which the law has been rendered so ineffective. The policy judgment driving it—that we should be cautious in stopping mergers because of the good they might do—turns out to have effectively no support. Meanwhile, the theory that mergers can do harm is well established, and empirical corroboration is growing and real. The balance between false positives and false negatives should be reset.

I. A Brief History and Legal Context: Mergers Go

Systematically Unregulated

There were not always corporate acquisitions in the United States, at least in routine numbers. Before the turn of the twentieth century, state corporation laws sharply limited acquisitions.16Merger, combination, and ownership of one corporation’s stock by another was mostly illegal in the United States until a set of New Jersey statutes of the 1880s and 1890s. The restrictions were driven in part by popular hostility to accumulations of capital or private power. See Fletcher Cyclopedia of Corporations § 2 (2013) [hereinafter Fletcher Cyclopedia]; Nelson Ferebee Taylor, Evolution of Corporate Combination Law: Policy Issues and Constitutional Questions, 76 N.C. L. Rev. 687, 695–753 (1998). Acquisitions were also probably hindered by a lack of limited-liability incorporation and modern capital markets.17See George J. Stigler, Monopoly and Oligopoly by Merger, 40 Am. Econ. Rev. Papers & Proc. 23, 28 (1950). Even during the late 1800s, when mergers were finally freed up by less restrictive state laws and easier access to capital, they were met with antitrust challenges and popular opposition. However, mergers finally arrived in numbers around the turn of the twentieth century, and when they did, they exploded. A decade-long wave of mergers began in 1895 that is still known as “the Great Merger Movement.” Historians disagree over its causes,18Several possible explanations of the Great Merger Movement are advanced in careful histories on an extensive record, including that it was an efficiency enhancing hunt for scale economies and vertical rationalization. See Alfred D. Chandler Jr., The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business (1993). For an argument that it was at least partly a scramble to reduce excess capacity following the depression of 1893, see Herbert Hovenkamp, The Opening of American Law: Neoclassical Legal Thought, 1870–1970 (2014); that it was just the understandable reaction of an entire society struggling to find order in what seemed like worsening chaos, see Louis Galambos, The Emerging Organizational Synthesis in Modern American History, 44 Bus. Hist. Rev. 279, 282 (1970); that indeed it may have been inadvertently caused by antitrust law itself, see George Bittlingmayer, Did Antitrust Policy Cause the Great Merger Wave? 28 J. L. & Econ. 77 (1985); or that, after all is said and done, it really was just the hunt for supracompetitive monopoly profits that most people always thought it was, see Naomi R. Lamoreaux, The Great Merger Movement in American Business, 1895–1904 (1988). Whatever its deeper motives, it appears to have been coordinated in part by a speculative, oversold, Wall Street investment scheme. See Gabriel Kolko, The Triumph of Conservatism: A Reinterpretation of American History, 1900–1916 (1963); Ron Chernow, House of Morgan (1990); Stigler, supra note 17, at 30 (merger “permitted a capitalization of prospective monopoly profits and [their] distribution . . . to the professional promoter,” enabling “a Morgan or a Moore to enter a new and lucrative industry: the production of monopolies”). but in its course it caused the elimination of thousands of firms and was the largest business consolidation in history.19See generally Lamoreaux, supra note 18.

The experience since has been one long stream of merger activity, punctuated every few decades by further massive waves. There have been perhaps five or more major waves since the Great Merger Movement, each on some measures larger than the last, reshaping whole sectors.20See F. M. Scherer, A New Retrospective on Mergers, 28 Rev. Indus. Org. 327, 328 fig.1 (2006). While determining whether there has been a “wave” at any given time is itself a complicated empirical problem,21See generally Klaus Gugler, Dennis C. Mueller & Michael Weichselbaumer, The Determinants of Merger Waves: An International Perspective, 30 Int’l J. Indus. Org. 1 (2012). Indeed, perceptions that there have been waves appear sometimes to be wrong. Scherer, supra note 20, at 328 fig. 1. no one doubts that there have been a half-dozen or so. Interestingly, each merger wave has had its own peculiar character. After the Great Merger Movement, which mainly consisted of horizontal mergers and often generated near-monopoly in particular sectors, a wave in the 1920s consisted of smaller deals that have been called “merger for oligopoly.”22See Stigler, supra note 17, at 31–33. Conglomerate deals dominated another wave during the 1960s, and another wave in the 1980s involved large deals and new financial or strategic novelties, including heavy leverage and hostile takeover. Another wave in the 1990s culminated in the dot-com bust of (circa) 2001, and perhaps one or two more have occurred since.23See Grocer, supra, note 1. In addition to the fact that mergers come in waves, there is the interesting and poorly-explained fact that waves are, to some degree, industry-specific. In each given wave, merger activity will be most intense in one or a few industries.24See infra notes 183–84 and accompanying text.

The law, for its part, has always imposed various limits on this enthusiasm, though it probably only meaningfully constrained mergers during short episodes. Mergers have predominately been addressed through three areas of law: corporate, securities, and antitrust law. The history of these laws’ merger rules is a fascinating topic on its own, fraught with confusion and ideology. Waves of mergers have generally led to some public controversy and have often prompted legal reforms. Reform efforts have occasionally been so major that they influenced presidential elections or whole political eras. In every case, however, reforms have faded, often quickly, when enforcement proved politically costly. These varying efforts and the political challenge they pose reflect America’s complex, changing, and often confused efforts to reconcile popular fear of corporate power with a generally liberal political philosophy that favors private enterprise.25These themes are discussed at much greater length in Chris Sagers, United States v. Apple: Competition in America 43–53 (2019), and Gary Gerstle, The Protean Character of American Liberalism, 99 Am. Hist. Rev. 1043 (1994). And so it is that after a century of popular concern and legal efforts to constrain them, mergers are more prevalent now than at any previous time and are largely free of meaningful legal constraints.

The rest of this Part explores these policy trends and sets out the major legal rules that currently govern mergers and acquisitions.

A. Corporate and Securities Law: Shareholder and Constituency Protections

For the most part, corporate and securities law rules governing mergers serve the routine goal of protecting shareholder value. Passive investors are thought to face various threats in change-in-control transactions. State corporate law attempts to protect passive investors with procedural requirements, the “appraisal” remedy, and the general demand that fiduciaries take care for shareholder value. Hostile takeovers in particular are subject to special fiduciary protections.26See generally Theresa A. Gabaldon & Christopher L. Sagers, Business Organizations 697–792 (2d ed. 2018) (canvassing the statutory procedures and fiduciary protections applicable to corporate control transactions). However, passive shareholders are not the only concern of corporate and securities law. State anti-takeover laws and Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) oversight under the Williams Act protect other constituencies.27The Williams Act, Pub. L. No. 90–439, 82 Stat. 454 (1968), (codified, as amended, at 15 U.S.C. §§ 78m(d)-(e), 78n(d)-(f)); see infra notes 39–43 and accompanying text.

Corporate control transactions generally require approval by target-firm shareholders and directors.28See generally Del. Code Ann. tit. 8, subch. IX; Rev. Mod. Bus. Corp. Act chs. 11-12 (2003). More generally, the law protects shareholders by imposing fiduciary duties on officers and directors and insists that management make their decisions in the interests of the shareholders.29See, e.g., Shlensky v. Wrigley, 237 N.E.2d 776, 180–81 (Ill. Ct. App. 1968); Dodge v. Ford Motor Co., 17 N.W. 668 (Mich. 1919); Blasius Indus., Inc. v. Atlas Corp., 564 A.2d 651 (Del. Ch. 1988) (citing Schnell v. Chris Craft Indus., 285 A.2d 437 (Del. 1971)); Fletcher Cyclopedia, supra note 16, § 1035.50 (2010). Consequently, managers negotiating, approving, and recommending sale-of-control transactions must ensure that shareholders receive “fair value.”30Smith v. Van Gorkom, 488 A.2d 858, 864 (Del. 1985); Weinberger v. UOP, Inc., 457 A.2d 701, 710–15 (Del. 1983). Even where full business-judgment-rule deference is available, the managers are obliged to investigate fair value adequately, and, in principle, can be responsible for a breach of their fiduciary duty to shareholders if they fail.31Van Gorkom, 488 A.2d at 872–74. Shareholders are also protected by the statutory appraisal remedy when their firms are acquired, under which dissenting shareholders can sometimes ask the courts to revalue their shares.32See generally 15 Fletcher Cyclopedia, supra note 16, ch. 61. Though it is a limited remedy in several ways, appraisal litigation has blossomed in recent years.33See Audra Boone, Brian Broughman & Antonio J. Macias, Merger Negotiation in the Shadow of Judicial Appraisal, 62 J. L. & Econ. 281 (2019); Wei Jiang, Tao Li, Danqing Mei & Randall Thomas, Appraisal: Shareholder Remedy or Litigation Arbitrage?, 59 J. L. & Econ. 697 (2016); Charles R. Korsmo & Minor Meyers, Appraisal Arbitrage and the Future of Public Company M&A, 92 Wash. U. L. Rev. 1551 (2015).

In the last several decades, a set of narrower state fiduciary rules evolved to deal with the particular problem of hostile takeovers and the entrenched managements who often resist them. Hostile takeover is thought to be desirable to target-firm shareholders, both because they can enjoy large premiums and because hostile deals might unseat ineffective managers. Incumbent management, however, usually attempts to stop those deals to protect their interests; thus, there is an inherent tension. Courts recognized the tension by mid-century, and by 1964 they developed a modest rule to curtail it.34Cheff v. Mathes, 199 A.2d 548, 554–55 (Del. 1964). They took renewed interest during the period of hostile takeovers of the mid-1980s and substantially toughened their oversight of incumbent managers. This was in part because the 1980s takeover wave generated substantial public concern and, in part, because it spawned a complex new world of anti-takeover defenses, deal protections, and hard-fought, multi-party acquisition battles.35Takeover defenses and deal protections are steps that firms take to protect themselves from hostile takeover. These can be as simple as self-tenders to buy back some of the firm’s own stock, and as complex as elaborate “poison pill” arrangements. See generally Richard A. Booth, The Promise of State Takeover Statutes, 86 Mich. L. Rev. 1635, 1659–66 (1988). Starting in 1985,36Unocal Corp. v. Mesa Petroleum Co., 493 A.2d 946 (Del. 1985). the Delaware Supreme Court enhanced the mild restrictions it had traditionally put on management self-defense.37Id. at 955. Under Unocal, directors are in breach of their fiduciary duties if they adopt anti-takeover defenses that are not proportionate and based on reasonable investigation. The Unocal rule applies to all defensive measures, whenever adopted, even if adopted when no hostile takeover attempt is pending. Moran v. Household Int’l, Inc., 500 A.2d 1346, 1350, 1355–57 (Del. 1986). A special rule applies to defensive measures that interfere with shareholders’ voting rights, such as by packing board seats or moving election dates to thwart proxy efforts. Such actions require some “compelling justification.” See Blasius Indus., Inc. v. Atlas Corp., 564 A.2d 651, 661–63 (Del. Ch. 1988). In certain special cases, directors are entirely precluded from stopping a takeover and can only take action to ensure the highest premium price.38Revlon, Inc. v. MacAndrews & Forbes Holdings, Inc., 506 A.2d 173 (Del. 1986).

A very interesting part of this history, and further evidence of how American business regulation is frustrated by political ambivalence, is that merger and acquisition rules are often internally contradictory. The rules discussed so far effectively favor changes in control, especially the fiduciary rules for hostile takeovers. The rules encourage changes in control because shareholders stand to gain financially from control premiums.

But separate reforms arose around mid-century, when America saw its first real incidence of hostile takeovers—first during the 1960s and then with greater intensity during the 1980s39Strictly speaking, despite popular perception, most control transactions in the 1980s were not hostile; the percentage of transaction that were hostile was probably no more than about 14%. See, Gregor Andrade, Mark Mitchell & Erik Stafford, New Evidence and Perspectives on Mergers, 15 J. Econ. Persp. 103, 104 (2001). More of them occurred as compared to the past; however, several takeovers were very large and achieved extraordinary attention, which drove a variety of legal reform efforts. Along with them came certain other innovations that seemed to many jarring and dangerous, including heavily leveraged going-private transactions and seemingly risky financial innovations, such as takeovers funded with junk bonds.—which sought to protect incumbent managers and local communities. This body of rules cuts the other way. These separate rules seek to discourage takeovers, or at least slow them down and control them, because of the damage they might do. The rhetoric driving these rules could sometimes be vitriolic, and anti-takeover animus often ran high. While debating the bill that eventually became the Williams Act in 1968, one co-sponsor called tender offerors “pirates,”40111 Cong. Rec. 28, 257 (1965) (statement of Sen. Harrison A. Williams). and another compared hostile takeover to rape.41113 Cong. Rec. 857–58 (1967) (statement of Sen. Thomas H. Kuchel). For what it is worth, under pressure from academics and securities regulators, that particular bill took on a policy of neutrality, seeking only to protect target shareholders from non-disclosure and coercion. Under that law as adopted, plus several SEC rules interpreting it during the 1980s, meaningful acquisitions of public company stock require certain disclosures, and must comply with a timeline and various procedural protections.42Namely, tender offer proponents must make disclosures with the SEC and target shareholders, 15 U.S.C. § 78n(d)(1); Rule 14d-6, 17 C.F.R. § 24014d-6 (2010); tender offers must be held open for twenty business days after the offer is first made, SEC Rule 14e-1(a), 17 C.F.R. § 240.14e-1(a) (2010); tendering shareholders are given a period during which their tender can be withdrawn, § 14(d)(9), 15 U.S.C. § 78n(d)(9); shares must be purchased pro rata from each tendering shareholder if the offer is oversubscribed, § 14(d)(6), 15 U.S.C. § 78n(d)(6); and offerors must follow a “best price” rule, under which if the proposed purchase price is increased during the pendency of the offer, that higher price must also be paid, even to shareholders who may already have tendered, § 14(d)(7), 15 U.S.C. § 78n(d)(7). Tender offers are also subject to a special anti-fraud rule, § 14(e), 15 U.S.C. § 78n(e). See generally Arnold S. Jacobs, The Williams Act: Tender Offers and Stock Accumulations (2020); Edward F. Greene, Regulatory and Legislative Responses to Takeover Activity in the 1980s: The United States and Europe, 69 Tex. L. Rev. 1539, 1544–56 (1991).

Similarly, since the perceived takeover crisis of the 1980s, many states have adopted “anti-takeover statutes” to limit control changes. Generally, they sought to protect communities and local interests from the dislocations of hostile takeover or movement of firms out-of-state.43The number and variety of these statutes is large. The first wave, which proliferated during the 1980s, were mostly “control share” statutes, which imposed additional procedures or target-shareholder rights wherever a bidder acquired some specified minimum of the shares of a firm incorporated in the particular state. Later generations of anti-takeover statutes empowered incumbent management to defend against unfriendly acquisitions, as by specifically disavowing Delaware’s Unocal and Revlon duties, or by authorizing specific defensive measures. See generally Michal Barzuza, The State of State Antitakeover Law, 95 Va. L. Rev. 1973 (2009); Booth, supra note 36, at 1670–81. On the various concerns that motivated these many laws, and the particular concern of many of them to protect local communities and non-shareholder constituencies, compare Alan E. Garfield, Evaluating State Anti-Takeover Legislation: A Broadminded New Approach to Corporation Law or “A Race to the Bottom”?, 1990 Colum. Bus. L. Rev. 119 (1990), with Lyman Johnson & David Millon, Missing the Point About State Takeover Statutes, 87 Mich. L. Rev. 846 (1989), and Lyman Johnson & David Millon, Misreading the Williams Act, 87 Mich. L. Rev. 1862 (1989). Various statutory and regulatory controls have been proposed e that would limit or discourage takeovers, including miscellaneous tax rules,44See, e.g., Kevin J. Murphy, Executive Compensation: Where We Are, and How We Got There, in 2A Handbook Of The Economics Of Finance 212, 302 (George Constantinides et al. eds., 2013) (noting tax penalties on some sizeable golden parachute payments in takeovers). an interpretation of a Federal Reserve lending rule modestly limiting leveraged deals,45See Greene, supra note 42, at 1553–54 (discussing interpretation of Regulation G). and a spate of attempts by Democrats in Congress to augment the Williams Act.46For example, Jensen lists more than twenty separate bills introduced in 1985 alone that would have limited or added new oversight of hostile takeovers. Michael C. Jensen, The Takeover Controversy: Analysis and Evidence, in Knights, Raiders, and Targets: The Impact of Hostile Takeover 314 (John C. Coffee, et al., eds. 1988) [hereinafter Jensen, The Takeover Controversy]; see also S. Rep. No. 265–100 (1987).

This mish-mash of disparate rules has occasionally imposed some limits on mergers, and during a few recent periods, they have generated significant amounts of important litigation. For the most part, however, these rules have made little impact; at the moment, they are mostly effectively unenforceable. So long as no one negotiating a deal is conflicted, garden-variety fiduciary challenges to takeover are analyzed under the business-judgment-rule. Fiduciary Challenges under that standard are all but literally unwinnable. When plaintiffs once scored a victory in a closely watched case at the beginning of the 1980s takeover wave,47Smith v. Van Gorkom, 488 A.2d 858, 858 (Del. 1985). state legislatures quickly rendered it almost completely inert.48As leading examples, Del. Code Ann. tit. 8, § 102(b)(7) (West 2022) and Rev. Mod. Bus. Corp. Act § 2.02(b)(4) (2003) both authorize corporations to bar money damages recovery against directors for mere, unconflicted breaches of the duty of care. Most Delaware corporations have elected to protect their directors under section 102(b)(7). Accordingly, money damages are unavailable unless plaintiff can allege some conflict or illicit gain, and the incentive to sue is drastically reduced. See, e.g., James D. Cox & Randall S. Thomas, Delaware’s Retreat: Exploring Developing Fissures and Tectonic Shifts in Delaware Corporate Law, 42 Del. J. Corp. L. 323, 334 (2018). Even in the presence of an explicit conflict of interest, as when minority shareholders are misled or coerced into sale by a parent corporation,49See, e.g., Weinberger v. UOP, Inc., 457 A.2d 701, 710–12 (Del. 1983). recent doctrinal innovations in Delaware have made it possible for merging firms in essentially all circumstances to secure business-judgment treatment and make all claims against them easily dismissible.50Namely, Kahn v. M & F Worldwide Corp., 88 A.3d 635 (Del. 2014), held that in a parent-subsidiary merger—in which by definition the parent is a fiduciary acting under conflict of interest—defendants can avoid the plaintiff-friendly duty of loyalty standard by conditioning merger approval on certain specific procedures. The business judgment rule applies if the merger is conditioned on negotiation by a fully independent board on behalf of the subsidiary and approval by the subsidiary’s fully informed shareholders. Id. at 644. Accordingly, in the wake of all these changes, Delaware fiduciary litigation has ground down to nearly nothing. Meanwhile, the Williams Act was never very restrictive to begin with, and state anti-takeover statutes are mainly compliance obligations that rarely impose meaningful limits.

Finally, while there has been something of a renaissance in appraisal litigation and while early evidence suggests it may have generated shareholder benefits,51Boone et al., supra note 33; see also Albert H. Choi & Eric Talley, Appraising the “Merger Price” Appraisal Rule, 34 J. L. Econ. & Org. 543 (2018) (setting out a formal model predicting that the availability of a robust appraisal remedy leads to higher merger prices, notwithstanding market efficiency). serious caveats apply. First, appraisal is subject to several limits that will make it unavailable or unrealistic in many cases,52Appraisal, generally, is not very useful for non-institutional shareholders, because of its cost. While it can be brought on contingency terms, and while courts can award attorney fees at their discretion, it is not generally brought on a formal class basis, and fees are not guaranteed. See Fletcher Cyclopedia, supra note 17, at § 7164.10. It is also subject to certain exclusions. Most importantly, both Delaware and Model Act jurisdictions generally deny appraisal rights where the target is publicly traded, unless the deal requires its shareholders to accept something other than liquid securities or cash. See Del. Code. Ann. tit. 8, § 262(b)(1) (2022); Rev. Mod. Bus. Corp. Act § 13.02(b)(1) (2003). Thus, appraisal is unavailable for many large transactions. and there is indication that courts may soon restrict it further.53See DFC Glob. Corp. v. Muirfield Value Partners, L.P., 172 A.3d 346 (Del. 2017) (accepting conditionally actual deal price as strong evidence of fair price where circumstances suggest market efficiency). More importantly, hedge funds bring a large proportion of current appraisal litigation, and there is real uncertainty about whether it benefits other shareholders or anyone else. But fundamentally, even effective appraisal—and, for that matter, most of the corporate law of mergers and acquisitions—ignores the social problem at the heart of this Article. An appraisal claim aims to prove that a takeover premium is too low. Its effect would exaggerate its estimate of the social value of acquisitions even further when that value appears not to exist.

B. Competition Protections

A separate and very different regime regulates mergers and acquisitions under antitrust law, which serves different goals and constituencies. Since 1914, section 7 of the Clayton Act has prohibited business combinations whose “effect . . . may be substantially to lessen competition, or to tend to create a monopoly.”5415 U.S.C. § 18.

Over its long and complicated history, antitrust merger law has probably not been very effective. A recurrent theme over the course of this history has been a struggle between Congress and the courts over whether enforcement would be vigorous and meaningful—as Congress has repeatedly indicated was its intention—or restrained and cautious. Every few decades Congress intervenes to shore it up, but each time the courts have re-construed the law in ways favorable to defendants. That was true of the initial adoption of the basic merger law, Clayton Act section 7, as well as each significant reform thereafter.55Congress has revisited merger legislation many times, essentially always to strengthen enforcement, and often enough to reverse perceived judicial resistance to it. In an often-told story, § 7 itself was meant to correct the courts’ failure to control concentration with the only federal law then available, the Sherman Act. See William Letwin, Law and Economic Policy in America: The Evolution of the Sherman Antitrust Act 267–78 (1965); Martin J. Sklar, The Corporate Reconstruction of American Capitalism, 1890–1916: The Market, the Law, and Politics 289–332 (1988); Lawrence A. Sullivan, Warren S. Grimes & Christopher L. Sagers, The Law of Antitrust: An Integrated Handbook § 8.1a (3d ed. 2015). Over its first decades, however, neither section 7 nor the Sherman Act was used effectively as a merger law. Popular frustration with weak enforcement and the perceived growth of concentration culminated in the 1941 final report of the Temporary National Economic Committee and an influential study of the Federal Trade Commission. Temp. Nat. Econ. Comm., Final Report and Recommendations 38–40 (1941); Fed. Trade Comm’n, The Merger Movement – A Summary Report in Annual Report for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30 1948, at 16–22 (1948) [hereinafter Fed. Trade Comm’n, The Merger Movement]. Matters perhaps reached their breaking point after a much-criticized decision, United States v. Columbia Steel Co., 334 U.S. 495 (1948), approved what was perceived to be another large and dangerous steel merger. Note, Section 7 of the Clayton Act: A Legislative History, 52 Colum. L. Rev. 766, 768 & n.10 (1952). There followed the storied adoption of the Celler-Kefauver Amendments of 1950, ch. 1184, 64 Stat. 1125 (1950), widely understood to intend stricter enforcement, and a string of decisions during the years of the Warren Court giving those amendments life that were stricter than federal merger control had ever been. See infra notes 57–60 and accompanying text. But barely more than ten years after this jurisprudence began to take root, a Supreme Court repopulated by the large number of Richard Nixon’s appointees undermined it in a set of decisions that would largely end merger enforcement as a meaningful institution. See infra notes 61–67. Indeed, even as Congress was in the midst of adopting another historic, pro-enforcement reform—the system of pre-merger review created by the Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act of 1976, Pub. L. No. 94–435, 90 Stat. 1383 (1976), now codified as Clayton Act § 7a, 15 U.S.C. § 18a— that same Supreme Court announced one of the more surprising retrenchments in the law’s history. Though section 7 had been in effect for sixty years and substantially amended to expand its coverage, the Burger Court purported to discover in 1975 that the law had in fact been misread as applying too broadly. The Court held that it applied only to mergers that were genuinely interstate in character, in that the firms involved were in different states. United States v. Am. Bldg. Maint. Indus., 422 U.S. 271, 276 (1975). Learned commentators met that announcement with surprise and consternation, see, e.g., Antitrust Procedural Improvements and Jurisdictional Amendments: Hearings Before the H. Subcomm. on Monopolies and Com. L. of the H. Comm. on the Judiciary, 108, 111-12, 96th Cong., 1st Sess. (1979) (statement of Eleanor Fox), and Congress quickly reversed it, Antitrust Procedural Improvements Act of 1980, Pub. L. No. 96–349, § 6(a), 94 Stat. 1154, 1157 (1980) (codified as amended at 15 U.S.C. § 18). Most significant for the law’s modern life was a 1950 amendment to section 7,56Celler-Kefauver Act, Pub. L. 81–899, 64 Stat. 1125 (1950). on the heels of what was perceived as a wave of consolidation in the 1940s and growing popular dissatisfaction with underenforcement.57See, e.g., Fed. Trade Comm’n, The Merger Movement, supra note 56 (government study influential during the period of Clayton Act reform, documenting rise in concentration). The Supreme Court, finding in the legislative history a desire to toughen merger law,58Brown Shoe Co. v. United States, 370 U.S. 294, 315–23 (1962). For similar views of the legislative history, see Derek C. Bok, Section 7 of the Clayton Act and the Merging of Law and Economics, 74 Harv. L. Rev. 226, 231–38 (1960). deployed the amended law in a series of decisions during the 1960s that adopted simplified, streamlined, and extremely enforcement-friendly prophylactic rules. Most importantly, in the 1963 United States v. Philadelphia National Bank (PNB) decision,59United States v. Phila. Nat’l Bank, 374 U.S. 321 (1963). the Court adopted a still-used burden-shifting rule under which a merger can be found illegal on nothing more than the increased concentration in an already concentrated market.60Id. at 362–63. Nominally, the plaintiff’s demonstration of concentration statistics was only a prima facie showing, and defendant could rebut it with evidence that concentration alone did not prove market power. See id. The courts applied the rule very strictly, however, and for the first decade of its life the government always won on the prima facie showing. For a time, that innovation was very effective. Over the course of the next decade, the federal government won twelve merger cases before the Supreme Court and lost none.61Eleanor M. Fox, Antitrust, Mergers, and the Supreme Court: The Politics of Section 7 of the Clayton Act, 26 Mercer L. Rev. 389, 396–97, 408, 410 (1975).

However, vigorous antitrust merger enforcement met political hostility and quickly proved unsustainable. By 1974, just over a decade after PNB, a Supreme Court newly populated with Richard Nixon’s unusual number of appointments62For elaboration, see generally Chris Sagers, #LOLNothingMatters, 63 Antitrust Bull. 7, 20–21 n.69 (2018). announced a set of closely divided decisions reaching much more defense-friendly results.63The cases were United States v. Citizens & S. Nat. Bank, 422 U.S. 86 (1975) (6-3), United States v. Marine Bancorporation, Inc., 418 U.S. 602 (1974) (5-3), and United States v. Gen. Dynamics Corp., 415 U.S. 486 (1974) (5-4). Lower courts took them to significantly soften the PNB presumption and demand much more proof from merger plaintiffs.64As something of a historical accident, modern merger law has been made exclusively by the lower courts. The Supreme Court has not taken a merger case in many, many years. See Sullivan et al., supra note 56, at 476–79. Among the most influential lower court decisions were United States v. Baker Hughes Inc., 908 F.2d 981 (D.C. Cir. 1990), decided by a D.C. Circuit panel including then-Judges Clarence Thomas and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and United States v. Waste Mgt., Inc., 743 F.2d 976 (2d Cir. 1984). Because merger policy is almost inherently speculative—enforcement actions are usually brought prospectively before deals are consummated—the setting of evidentiary burdens largely determines which parties win or lose. At length, while PNB nominally remains the law, and is still cited as seminal,65Recent appellate opinions from a variety of circuits cite PNB as leading authority. See, e.g., FTC v. Advocate Health Care Network, 841 F.3d 460, 464, 467, 468, 469, 470, 474, 476 (7th Cir. 2016); FTC v. Penn State Hershey Med. Ctr., 838 F.3d 327, 344, 348 (3d Cir. 2016); Saint Alphonsus Med. Ctr.-Nampa Inc. v. St. Luke’s Health Sys., 778 F.3d 775, 783, 786 (9th Cir. 2015); Polypore Int’l, Inc. v. FTC, 686 F.3d 1208, 1213-18 (11th Cir. 2012). its rule is honored only in the breach. With some exceptions, only the very largest horizontal mergers are now challenged,66 John Kwoka, Mergers, Merger Control, and Remedies: A Retrospective Analysis of U.S. Policy 24–33 (2014) (showing that the effective threshold of concentration beyond which agencies will challenge mergers has substantially risen). and not infrequently even those claims lose67The government admittedly still wins merger cases, but the cases it wins are exclusively horizontal and involve massive concentration numbers. See, e.g., United States v. Anthem, Inc., 855 F.3d 345, 351 (D.C. Cir. 2017) (ruling for government, where merger would result in HHI as high at 3675); United States v. Aetna Inc., 240 F. Supp. 3d 1, 42–43 (D.D.C. 2017) (ruling for government, where merger would result in HHIs in most local markets of more than 5000). And plaintiffs still lose even the biggest cases. Consider, for example, T-Mobile’s acquisition of Sprint in 2020, a four-to-three merger in a market with high entry barriers and inelastic demand, see New York v. Deutsche Telekom, 439 F.Supp.3d, 179 228 (so finding), generating very high concentration numbers, id. at 206 (finding that merger would increase HHI by 679 points, to 3186). However, after the Justice Department approved the deal, on a transparently feeble package of remedial asset divestitures and problematic circumstances, a group of state Attorneys General brought their own suit and lost. Id. or just barely win.68Consider FTC v. Staples, Inc., 190 F. Supp. 3d 100 (D.D.C. 2016). Not so many years earlier, the FTC had blocked a merger between the same parties in a celebrated courtroom victory, FTC v. Staples, Inc., 970 F. Supp. 1066 (D.D.C. 1997), but the parties attempted to renew the deal in 2015, arguing that circumstances had changed. The new deal would generate breathtaking concentration numbers. On the market definition accepted by the court as fact, the merger would create a firm holding nearly 80%, and it would be fifteen times larger than its nearest rival. (In technical terms, the initial HHI of 3270 would increase by nearly 3000 points, to 6265). Staples, 190 F. Supp. 3d at 128. But what is truly amazing about the case is that the FTC barely won. As proof how weak the law has become, the defense was so confident they would win that they rested without putting on any evidence. Id. at 110. But even with no defense case at all, the court wrote that the case was close, that the decision posed serious challenges, and hinted that had there been just somewhat more evidence of likely entry, the government would have lost. See id. at 136 (“If Amazon Business was more developed [and more clearly ready to enter], the outcome of this case very well may have been different.”).

* * *

In the end, America’s long history of fretting over its hundreds of thousands of mergers and the tension between the fear of mergers’ bad consequences and the risk of mistakenly upsetting desirable business behavior, has left us in a remarkable state. The United States administers a regime of merger law that keeps thousands of attorneys, economists, and government officials employed. It entails substantial social costs,69Cf. Joe Sims & Deborah P. Herman, The Effect of Twenty Years of Hart-Scott-Rodino on Merger Practice: A Case Study in the Law of Unintended Consequences Applied to Antitrust Legislation, 65 Antitrust L. J. 865, 890–92 (1997) (early estimate of the administrative costs of the antitrust pre-merger clearance system). but virtually never constrains any transaction in any meaningful way. Given this extraordinary state of affairs, one would imagine not only that mergers do some good, but that they must generate really exceptional, dramatic, and measurable social gains. It would seem unreasonable to bend so far backwards to facilitate them unless they do. And yet, at least so far as any evidence has been able to establish, they do not.

II. The Theoretical Foundation on Which Mergers Become

Unregulated: That There Must Be Something Good About Them

One major contributor to the ambivalent politics of merger history is the diverse body of theories that predict social benefits from mergers. They are of basically three varieties: (a) the argument that, first and foremost, mergers generate “efficiencies” or “synergies” or in some other way deliver net social gain; (b) closely related theoretical controversies over whether concentration in itself can indicate social injury or risk—whether “big” is “bad”—as was implied in antitrust policy under the Warren Court; and finally, (c) the rather different argument that policy should foster a “market for corporate control,” because the possibility of hostile acquisition disciplines incumbent management and directs assets to the most capable owners.

These theories are related. Each arose or was significantly advanced during the revolution among American economists commonly thought of as a “conservative” revolution, and each came to exert extensive influence on the law. But while each came to face substantial academic critique and none now holds more than a controversial position within academia, their influence on the law has remained unchanged.

A. Efficiencies

The chief theoretical justification for growth by acquisition has always been efficiency. In various ways, proponents of merger activity claim that firms can make their goods better or more cheaply if they can do it at a larger volume, and that for various reasons growth by acquisition might be preferable to internal growth. Theorists have suggested a huge range of possible mechanisms by which growth could generate efficiency.70The specific mechanisms by which growth or consolidation could drive efficiency are, at least in principle, many. Producing at larger volume can generate scale economies where fixed costs are comparatively large. See F.M. Scherer & David Ross, Industrial Market Structure and Economic Performance 97 (3d ed. 1990). Integrating different technical processes in one firm can sometimes make the processes more technologically efficient, regardless of whether scale changes. See, e.g., M.A. Adelman, Integration and Antitrust Policy, 63 Harv. L. Rev. 27, 31–32 (1949) (describing the potential savings in steel making if the furnace for making pig iron and the furnace for finishing it into steel are located in the same factory, avoiding the cost of heating the same materials twice). Economists and business theorists have suggested any number of other mechanisms that might lower cost or raise quality of production, many of which in principle could be improved through growth or consolidation. No one seriously doubts that efficiencies can occur with growth or consolidation, and real-world evidence exists.71See, e.g., Aloke Ghosh, Increasing Market Share as a Rationale for Corporate Acquisitions, 31 J. Bus. Fin. & Acct. 209 (2004); Joachim Schwalbach, Directorate General for Economic and Financial Affairs, European Comm’n, Economies of Scale in Intra-Community Trade 1998 Econ. Papers No. 68, http://aei.pitt.edu/36976/1/A3011.pdf [https://perma.cc/48V9-7ZSC]; Aubrey Silbertson, Economies of Scale in Theory and Practice, 82 Econ. J. 369 (Special Issue) (1972). However, there is serious reason to doubt that efficiencies are significant or common in mergers of the size and competitive risk relevant to public policy, much less that they commonly outweigh the risks posed.

Before the mid-20th century, traditional arguments for merger efficiencies tended to be simple-minded generalities. Even now, it is often said without elaboration that mergers will make bigger firms “stronger competitors” or better able to confront buyers or suppliers with market power.72See, e.g., Jamie Henikoff Moffitt, Merging in the Shadow of the Law: The Case for Consistent Judicial Efficiency Analysis, 63 Vand. L. Rev. 1697, 1698, 1702 (2010). In general, such claims have not been taken too seriously because simple economics implies that competition improves efficiency more than a lack of it does.73Economists have cited the efficiency benefits of competition at least since Adam Smith: Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations 132 (Vintage Books 2020) (1776) (“Monopoly…is a great enemy to good management, which can never be universally established but in consequence of that free and universal competition which forces everybody to have recourse to it for the sake of self-defence.”). See also F.M. Scherer, Industrial Market Structure and Economic Performance 38 (2d ed. 1980); see also infra notes 195-201 and accompanying text (discussing the X-efficiency literature). However, economists began working out merger efficiencies with more theoretical rigor in the 1960s, first in a key 1968 paper by Oliver Williamson.74Williamson’s first paper was Oliver E. Williamson, Efficiencies as an Antitrust Defense: The Welfare Tradeoffs, 58 Am. Econ. Rev. 18 (1968) [hereinafter Williamson, Efficiencies]. He corrected and expanded on the original paper in Oliver E. Williamson, Economies as an Antitrust Defense: The Welfare Tradeoffs, in Readings in Industrial Economics (C. Rowley ed. 1972), and Oliver E. Williamson, Economies as an Antitrust Defense Revisited, 125 U. Pa. L. Rev. 699, 699–700 (1977) [hereinafter Williamson, Revisited]. See generally Alan A. Fisher & Robert H. Lande, Efficiency Considerations in Merger Enforcement, 71 Calif. L. Rev. 1580, 1583 (1983) (noting the seminal role of Williamson’s papers in the handling of merger efficiencies). Williamson’s insight was that under certain assumptions and for a simple mathematical reason, efficiencies could sometimes outweigh the deadweight loss of increased market power. He set out a formal demonstration, along with a table of striking numerical results, showing that mergers should usually be net socially desirable. The central theoretical insight was simple: deadweight loss affects only those sales lost by the monopolist’s price increase, whereas efficiency gains are spread across the firm’s entire remaining production.

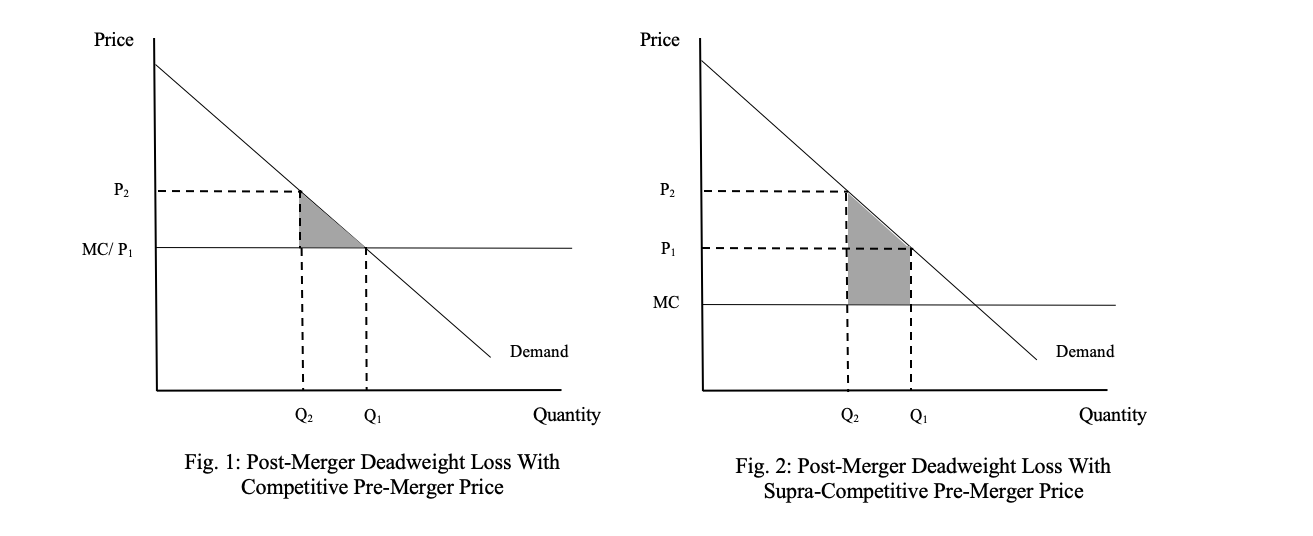

It is worth dwelling on the serious problems that complicate Williamson’s model, because it remains a cornerstone of modern merger policy even though its weaknesses are well known.75For criticism, see Herbert Hovenkamp, Appraising Merger Efficiencies, 24 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 703, 715–24 (2017); John Kwoka, The Changing Nature of Efficiencies in Merger Analysis, 60 Antitrust Bull. 231, 233 (2015); Richard A. Posner, The Social Costs of Monopoly and Regulation, 83 J. Pol. Econ. 807, 821 (1975). Williamson acknowledged some of the weaknesses himself.76See Williamson, Revisited, supra note 74, at 710–13; Williamson, Efficiencies, supra note 75. First, he assumed a perfectly competitive pre-merger market that develops market power after just one merger. That is extremely unlikely empirically, and it is also legally irrelevant because under antitrust law—as it has existed for more than forty years—mergers in competitive markets are effectively per se legal. But it also seriously distorts the striking numbers he was able to generate.77Hovenkamp, supra note 76, at 715–24; Lars-Hendrik Röller, Johan Stennek & Frank Verboven, Efficiency Gains From Mergers, in European Merger Control: Do We Need An Efficiency Defence 108 (Fabienne Iizkovitz & Roderick Meiklejohn eds., 2006). As has now been shown several times with a useful graphical representation,78The graphic is reproduced in an Appendix. For earlier presentations, see Hovenkamp, supra note 76, at 717; Frank Mathewson & Ralph Winter, The Analysis of Efficiencies in Superior Propane: Correct Criterion Incorrectly Applied, 20 Can. Comp. Rec. 88, 96 (2000). it matters quite a lot in measuring the effects of a merger whether the pre-merger market was competitive or not. Price increases imposed on a perfectly competitive market cause relatively little harm because marginal consumers were already nearly indifferent between having the good and not having it. But if the pre-merger market already reflects substantial market power—as will be the case in all mergers likely to be challenged under antitrust law—even consumers at the margin would have paid more than marginal cost for the good. When output goes down after the merger, that benefit they enjoyed by having the product will be a deadweight loss. Real-world cases have shown that this distortion can be very large.79In a closely watched Canadian antitrust case, Comm’r v. Superior Propane Inc., 2000 Comp. Trib. 15, the court permitted a merger to an effective monopoly on a finding that efficiencies hugely outweighed deadweight loss. But it could only find that disparity because it assumed that pre-merger prices were competitive. A subsequent study more plausibly estimated a pre-merger overcharge and found post-merger deadweight loss to be 8.5 times larger than that measured by the Court, largely wiping out the estimated efficiency. See Mathewson & Winter, supra note 78, at 89, 91. Matthewson and Winter could calculate the pre-merger overcharge from an econometric estimate of demand elasticity at the pre-merger price (accepted by the court in its decision). Demand elasticity greater than one implies that price is above marginal cost. See id. at 90–91.

A second major problem is that Williamson hypothesized mergers in which there would be both a price increase (which will reduce quantity) and some cost reduction.80See Williamson, Efficiencies, supra note 74, at 18 n.2. But it is empirically unlikely that gains from scale would accompany a market power increase. For one thing, scale benefits likely won’t improve when output goes down. Though a merged firm can simultaneously increase its own scale while reducing total output, any scale benefits gotten that way are emphatically the kind that competition itself is supposed to produce.81Imagine that two firms each produce fifty units, but minimum efficient scale (MES) is seventy-five. If they merge, total output will go down, by at least twenty-five, but so will the merged firm’s average cost. But competition is precisely the mechanism that is supposed to generate this result. The two firms should fight for sales until one of them reaches MES, and if the other must exit the market, then that is an ordinary consequence of competition. Circumstances are likely unusual in which MES is so large that a market will support only a small number of firms. See infra notes 165–67 and accompanying text.It is also possible that an output-reducing merger could generate efficiencies other than scale economies, like improvements in management. Efficiencies of that kind tend to be very difficult to verify and unlikely to be merger specific. See U.S. Dep’t of Justice & Fed. Trade Comm’n, Horizontal Merger Guidelines § 10 (2010); Hovenkamp, supra note 75, at 711. Williamson himself claimed that the most likely efficiencies from merger would be transactional savings (he apparently thought scale efficiencies were unlikely). Those savings might be had where combination into a hierarchical firm was cheaper than complicated, contingent, long-term contracting. Williamson, Revisited, supra note 74, at 723–26. But as he acknowledged, complex contracting to achieve pro-competitive ends will occur mainly in vertical relationships, and perhaps conglomerate ones. Id. It is hard to imagine contracting problems solved by most horizontal mergers. Moreover, efficiencies from growth tend to be exhausted at a comparatively small scale.82See infra notes 165–67 and accompanying text. There was already some evidence to that effect at the time of Williamson’s article. See, e.g., Joe S. Bain, Advantages of the Large Firm: Production, Distribution, and Sales Promotion, 20 J. of Mktg. 336 (1956) (reporting results of study of 17 mostly concentrated industries, finding little evidence that MES could explain existing levels of concentration in most of them). Admittedly, the evidence that existed at the time faced the controversy typical of such developing ideas. Bain’s 1956 study, for example, has been criticized for its small and probably biased sample selection. See Stephen Davies, Minimum Efficient Size and Seller Concentration: An Empirical Problem, 28 J. of Indus. Econs. 287, 291 n.9 (1980). The model conceals other problems as well.83See Kwoka, supra note 75, at 233 (listing other problems).

In essence, Williamson made a perceptive mathematical observation about a rare, idiosyncratic set of hypothetical transactions that might never occur and would not be legally challenged if they did. Indeed, no such case has ever been identified in American merger law.84See Herbert Hovenkamp, Progressive Antitrust, 2018 U. Ill. L. Rev. 71, 90–92 (2018). Williamson predicted that such cases would be only “occasional”85See Williamson, Efficiencies, supra note 74, at 18. and repeatedly warned that his model was “naive.”86Williamson states as follows:“To be sure, the partial equilibrium welfare economics apparatus upon which I relied to display the welfare tradeoffs is a blunt instrument that can be used in an intimidating way. To forestall the risk that subtle and complex policy issues might be resolved in an undiscerning manner, I specifically labeled the simple welfare economics model as ‘naive’ and went on to introduce a number of economic and extra-economic qualifications that must be considered.”

Williamson, Revisited, supra note 74, at 701.

Nevertheless, the mere possibility of efficiencies still largely governs American merger policy. Courts, commentators, and policymakers still take for granted that very significant improvements in production cost or quality are commonly available through corporate combinations and consider it a serious risk that government interference in those transactions will inadvertently jeopardize gains that could have been realized. This idea infuses corporate and securities merger law, and, while its role in antitrust has been somewhat complex, it overwhelmingly drives antitrust as well.87Antitrust has long been ambivalent about efficiencies as a defense in litigated antitrust cases, and for much of its history refused to permit any demonstration of efficiency gains at all. See Timothy J. Muris, The Government and Merger Efficiencies: Still Hostile After All These Years, 7 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 729, 730–32 (1999). However, courts and agencies have incorporated the possibility of efficiency in a different way. They set the initial concentration threshold for an antitrust merger plaintiff’s prima facie showing under the PNB standard (see supra notes 62–71 and accompanying text) by asking at what level of concentration the likelihood of harm outweighs likely gains. This was the approach of the 1982 Merger Guidelines, see Fisher & Lande, supra note 74, at 1584–85, and observers since have continually urged that that the threshold be raised. See, e.g., Daniel A. Crane, Rethinking Merger Efficiencies, 110 Mich. L. Rev. 347, 348–50 (2011). That has in fact happened—the threshold has increased substantially. See supra note 69 and accompanying text.

B. The Disputed Relevance of Concentration: SCP, Entry Optimism,

and the Contestability “Uprising”

An argument for permissive merger policy closely related to the efficiency claims just discussed is that the size of corporations and the concentration of markets are themselves not relevant to public policy. The argument relates mainly to competitiveness and antitrust, and the claim is that size and concentration in and of themselves do not generate market power. “Big,” in other words, is not “bad.” In extreme forms, important theoretical movements have gone so far as to claim that even outright monopoly might generate no market power at all and claims even that radical have at times held sway in policy.

Perhaps more than any other issue, it was crucial to the mid-century economic revolution to argue that market concentration and firm size could not prove social harm. Up until that time, economists of the influential “Structure-Conduct-Performance” tradition (SCP) argued that concentration alone could predict bad outcomes from merger.88SCP was perhaps the first major contribution of industrial organization economics as an independent discipline, and was associated with founding figures in the field, principally economists Edward Mason of Harvard and his student Joe Bain of Berkeley. See generally Ewald T. Grether, Industrial Organization: Past History and Future Problems, 60 Am. Econ. Rev. Papers & Proc. 83 (1970); Timothy F. Bresnahan & Richard Schmalensee, The Empirical Renaissance in Industrial Economics, 35 J. Indus. Econ. 371 (1987). The SCP movement was said to be important to Warren-era merger policy because its specific premise was that concentration leads reliably and systematically to market power. See Herbert Hovenkamp, United States Competition Policy in Crisis: 1890–1955, 94 Minn. L. Rev. 311, 355–56 (2009). The movement was mainly empirical and rested on a well-established correlation between concentration and profit. The idea implied the significant policy argument that the law might regulate concentration for its own sake, without further investigating actual consequences.89For what it is worth, Mason, Bain, and their ilk were not critics of mainstream economic theory. They just found plausible a causal link between concentration and market power, which they thought was explained by collusion facilitated by concentration. They also believed they’d substantiated it empirically. See Hovenkamp, supra note 88, at 349–59; Richard Schmalensee, Collusion Versus Differential Efficiency: Testing Alternative Hypotheses, 35 J. Indus. Econ. 399, 399 (1987). The idea was basic to the PNB presumption and the strict antitrust law of the Warren Court era. During a harsh reactionary period, however, conservatives argued that government should disregard concentration entirely and regulate only conduct.90See, e.g., Yale Brozen, Concentration, Mergers and Public Policy (1982); Harold Demsetz, Two Systems of Belief About Monopoly, in Industrial Concentration: The New Learning 164 (Harvey J. Goldschmid, H. Michael Mann, & J. Fred Weston, eds. 1974). Those critics were so successful that not only did SCP fall out of favor, but empirical study of industry structure ended more or less altogether.91See Bresnahan & Schmalensee, supra note 88.

The critics did not doubt the basic empirical result underlying SCP—that concentration correlates with accounting profit. They generally acknowledged it as fact.92See, e.g., Sam Peltzman, The Gains and Losses from Industrial Concentration, 20 J. L. & Econ. 229, 229 (1977); see Schmalensee, supra note 90 (“Since the pioneering work of Joe Bain . . . a positive correlation between industry concentration and accounting measures of industry-average profitability has generally been accepted as a stylized fact.”). Instead, they attacked SCP’s causal reasoning.93Their critique very often began by observing that mid-century economists uncritically assumed that behavior inconsistent with perfect competition must be explained by monopoly. See, e.g., R.H. Coase, Industrial Organization: A Proposal for Research, in 3 Economic Research: Retrospect and Prospect: Policy Issues and Research Opportunities in Industrial Organization 59, 67 (Victor R. Fuchs ed., 1972), reprinted in R.H. Coase, The Firm, the Market, and the Law 57–74 (1988) (mocking mid-century economists when such “an economist finds something . . . that he does not understand, he looks for a monopoly explanation[,]” and because “in this field we are very ignorant, the number of ununderstandable practices tends to be rather large, and the reliance on a monopoly explanation, frequent.”); Harold Demsetz, Barriers to Entry, 72 Am. Econ. Rev. 47, (1982) [hereinafter “Demsetz, Barriers to Entry”] (“[T]he research custom of industrial organization economists during the post-World War II period . . . was to seek monopoly explanations for data not obviously or directly implied by the perfect competition model.”). Most importantly, they argued that no inference of market power could be drawn from accounting profits, which might entail no economic profit at all.94Accounting profits are simply revenue less the costs of inputs. Economic profits are revenue less the costs of those inputs (known by economists as “accounting costs”) plus a competitive rate of return to capital. The distinction is critical in economic theory because it is the reason firms might sometimes seem to earn excess “profits” without market power. Even firms in perfectly competitive markets might earn revenues in excess of accounting costs, but by definition their economic profits are still equal to zero. That is so because the investor returns needed to keep capital invested in the enterprise might vary with risk or other factors. The critics explained the concentration-profits correlation by efficiency or other advantages that might correlate with firm size,95See supra note 92; see also Michael Salinger, The Concentration-Margins Relationship Reconsidered, in Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 289 & n.7 (Arthur M. Okun & George L. Perry, eds. 1990) (discussing various explanations for apparent profits among critics of SCP). and they generated preliminary empirical support for it.96See generally Harold Demsetz, Industry Structure, Market Rivalry, and Public Policy, 16 J. L. & Econ. 1 (1973) (presenting descriptive statistical evidence that rates of return to small firms do not increase with concentration, as Demsetz expected if the prevailing explanation were correct that concentration facilitates collusion); see also Peltzman, supra note 92. For a time, it also appeared that the traditional concentration-profits correlation might have shrunk or disappeared during the 1970s. More recent evidence finds it to have returned in the early 1980s. If true, that result nicely coincides with the structural transformation and the return of substantial corporate profits so heavily implicated in more recent evidence. See Baker, supra note 12, at 13–18 & nn.30–35. Salinger suggests the temporary loss of the correlation may have been caused by import competition, which increased during the 1970s. Salinger, supra note 95, at 306–07. They further argued that if the profits typical of concentration were caused by anti-competitive behavior, they should invite entry.97See Peltzman, supra note 92. Rents could persist only if entry barriers were high, and conservative critics were skeptical that they could be.98See George Stigler, The Organization of Industry 67, 113–22 (1968); see also Demsetz, Barriers to Entry, supra note 93, at 47. They also contributed to the evolving industrial-organization theory of imperfect competition, purporting to show that the cartels or oligopoly interdependence that could generate economic profits should be difficult to sustain.99See generally George J. Stigler, A Theory of Oligopoly, 72 J. Pol. Econ. 44 (1964) (classic article formulating this influential view).