The Securities Law Disclosure Conundrum for Publicly TradedLitigation Finance Companies

Robert F. Weber*

* Associate Professor of Law, Georgia State University. The author acknowledges the assistance of participants at workshops hosted by the Temple University Beasley School of Law and the 2021 National Business Law Scholars Conference. Maya Steinitz and Tony Sebok also deserve recognition for both lighting my way through some of the obscurer realms of litigation finance and commenting on earlier drafts of this article.

Abstract

The Article examines a peculiar legal dilemma—implicating securities law, legal ethics, and evidence law—that arises when litigation finance companies (LFCs) become public companies. LFCs provide funding to litigants and law firms for prosecuting lawsuits in exchange for a share of the lawsuit recoveries. In recent years, LFCs have significantly altered the landscape of the civil justice system in common law jurisdictions. But their assets, which are just rights to proceeds from lawsuits, are notoriously opaque—who really can predict what a jury will do when it comes to liability and damages? When LFCs go public, this opacity frustrates public investors’ legitimate expectations to be able to understand the company’s accounts and operations. The problem is exacerbated by the applicable accounting rules, which outsource the task of valuing the assets to the LFCs themselves, vesting them with significant discretion to build their own financial statements. The resulting lack of clarity about basic valuation matters undermines the two main objectives of securities law: investor protection and market integrity.

From a securities law perspective, the normal solution to an opacity problem is more and better disclosure. However, concerns over the possible waiver of evidentiary protections flowing from the attorney-client privilege and the work-product doctrine complicate matters for LFCs. To avoid the possibility of waiver of privileged, confidential information (which would, in most cases, undermine the cases underlying their assets), LFCs are circumspect when it comes to disclosing any details of the valuation models for their assets, much less relevant details about specific cases. The shadow of privilege waiver thus chills the entirety of LFC disclosure practice, foreclosing it as an effective corrective to the intrinsic opacity of LFC accounts.

After detailing the sources and extent of this opacity problem, the Article explores two case studies. The first, involving the 2015 failure of Juridica Investments, illustrates how opaque LFC accounts can undermine the investor protection objective of securities law. The second, involving the 2019 “short attack” by hedge fund Muddy Waters on litigation funder Burford Capital, shows how the opacity problem can also undermine the market integrity objective. The Article concludes by laying out a framework for reform.

Introduction

For the past decade and a half, litigation finance companies (LFCs) have altered the landscape of the civil justice system in common law jurisdictions. They have empowered thousands of business litigants to vindicate their legal rights, chipped away at inbuilt advantages in settlement negotiations favoring large and repeat players, and catalyzed reform initiatives in areas long considered third rails in professional regulation, such as fee sharing. The continuing evolution of litigation finance is a phenomenon that all lawyers should register. Litigation finance will increasingly shape the institutional arrangements of dispute resolution practices as well as the broader financial and labor economics and ethical regulation of the legal profession.

This Article shifts the lens away from the robust ongoing analysis of the civil procedure,1See Anthony J. Sebok, White Paper on Mandatory Disclosure in Third-Party Litigation Finance, in Mandatory Disclosure Rules for Dispute Financing (N.Y. Univ. Sch. of L. Ctr. on Civ. Just David Siffert ed., 2021); Maya Steinitz, Follow the Money? A Proposed Approach for Disclosure of Litigation Finance Agreements, 53 U.C. Davis L. Rev. 1073 (2019) [hereinafter Steinitz, Follow the Money?]; Jonathan T. Molot, Litigation Finance: A Market Solution to A Procedural Problem, 99 Geo. L.J. 65 (2010). access to justice,2See Matthew A. Shapiro, Distributing Civil Justice, 109 Geo. L.J. 1473, 1509–12 (2021); Maya Steinitz, Incorporating Legal Claims, 90 Notre Dame L. Rev. 1155, 1161 (2015) [hereinafter Steinitz, Incorporating Legal Claims]. and legal ethics3See Elayne E. Greenberg, Hey, Big Spender: Ethical Guidelines for Dispute Resolution Professionals when Parties Are Backed by Third-Party Funders, 51 Ariz. State L.J. 131, 133 (2019); J. Maria Glover, A Regulatory Theory of Legal Claims, A Regulatory Theory of Legal Claims, 70 Vand. L. Rev. 221, 289–93 (2017); Victoria Shannon Sahani, Judging Third-Party Funding, 63 UCLA L. Rev. 388, 401 (2016); Maya Steinitz, Whose Claim Is This Anyway? Third-Party Litigation Funding, 95 Minn. L. Rev. 1268, 1323–25 (2011) [hereinafter Steinitz, Whose Claim?]; Anthony J. Sebok, Betting on Tort Suits After the Event: From Champerty to Insurance, 60 DePaul L. Rev. 453 (2011). implications of litigation finance to analyze, for the first time, how this burgeoning sector intersects with the securities law regime.4Wendy Couture has analyzed the unrelated issue of whether litigation funding agreements might be considered “securities” for purposes of the U.S. securities laws. See Wendy Gerwick Couture, Securities Regulation of Alternative Litigation Finance, 42 Sec. Regul. L.J. 5, (2014). When LFCs list their securities on public capital markets, they submit to a complex system of securities law and regulation—a regime oriented to two central objectives: the protection of investors and the preservation of market integrity.5See, e.g., H.R. Rep. No. 104-369, at 31 (1995), reprinted in 1995 U.S.C.C.A.N. 730, 730 (“The overriding purpose of our Nation’s securities laws is to protect investors and to maintain confidence in the securities markets, so that our national savings, capital formation and investment may grow for the benefit of all Americans.”); Int’l Org. of Sec. Comm’ns, Objectives and Principles of Securities Regulation 3 (2017), https://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD561.pdf [https://perma.cc/75TM-EEDP].

When LFCs go public, they encounter a conundrum resulting from the intrinsic opacity of litigation finance assets. Fundamentally, LFCs are in the business of advancing funds to litigants and their lawyers to finance the pursuit of litigation, in exchange for a return pegged to the proceeds of that litigation.6See discussion infra Part II.A. From the perspective of the LFC, a litigation finance asset can be considered a derivative contract where the underlying asset is a lawsuit.7See Litigation Finance Faces Ethical Quandaries, The Economist (Nov. 7, 2019) https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2019/11/07/litigation-finance-faces-ethical-quandaries [perma.cc/8AVK-6YPA] (analogizing lawsuits to derivative contracts); see R. Stafford Johnson, Derivatives, Markets, and Analysis ix (R. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2017) (explaining how a derivative contract derives value by a reference asset, referred to as the “underlying,” which would be the lawsuit in this context).

While there is arguably some room for classificatory discretion on the part of LFC accountants, most publicly traded LFCs take the (probably correct) position that the relevant accounting rules mandate that litigation finance assets be classified as “financial assets.” This position, in turn, requires the use of so-called “fair value accounting” practices. Where the LFC cannot look to any direct market prices nor even any indirect proxy market prices, it must “mark” (or record the fair value of) its assets according to its own internal valuation models. These internal valuation models unavoidably entail some quantum of brute discretion on the part of company management and their accountants. Just as importantly, under applicable accounting rules these “fair value” adjustments, which initially appear as balance sheet phenomena, flow directly through to the income statement.

As such, LFCs wield significant discretion in recording and reporting their assets’ value and operating income. Indeed, LFCs possess significantly more discretion than even other financial companies since adopting fair value accounting would require that all of their assets, lacking as they do any direct or indirect reference market prices, must be marked to internal valuation models. For perspective, it is common for publicly traded LFCs to have more than half of their reported income consist of subjective, discretionary fair value adjustments to their assets, frequently without the asset having yet realized any actual income from settlements or court judgments.8See infra notes 142-144 and accompanying text.

According to the normal logic of the securities laws in the U.S. and elsewhere, the solution to an accounting opacity problem would be enhanced disclosure concerning the assets and the models used to value them. Investors in a publicly traded LFC might like to know about the company’s specific valuations for particular assets, the company’s assessment of the likelihood of success on the merits for some of its larger assets, the litigants’ settlement negotiating leverage for those same assets, and so forth. However, LFCs not only possess uniquely opaque balance sheets, but they also are uniquely handicapped when it comes to producing clarifying, corrective disclosure to remedy that opacity.

This handicap results from concerns over the possible waiver of evidentiary protections flowing from the attorney-client privilege and the work-product doctrine. All of these desired disclosures are informed directly or indirectly by discussions, decisions, and consultations between the funded litigant and its attorneys, occasionally with the involvement of the LFC itself. To be sure, all public companies embroiled in material litigation face difficult trade-offs when balancing the competing directives of the securities laws (which usually demand greater disclosure) and the legal ethics rules and their evidence law adjuncts (which usually demand circumspection, if not outright silence).

The problem is particularly acute in the LFC context because virtually everything that is operationally relevant to an LFC revolves around active litigation—nearly every expected cash flow will originate from an active lawsuit. The risk here is that even a partial disclosure of privileged, protected information might open the door to court-ordered unveiling of materials that will materially prejudice and undermine the financed lawsuit—and the cash flows the LFC expects from it. As a result, concerns over privilege waiver cast a shadow over LFC disclosures, and this shadow chills efforts to speak frankly about LFC assets, even at the aggregate portfolio level.

Two recent episodes involving publicly traded LFCs serve as case studies for how these dynamics undercut the securities law norms of investor protection and market integrity. The first such case study focuses on the investor protection norm by recounting the collapse of Juridica Investments, Ltd. (Juridica), which in 2007 became the first LFC to go public. By 2015, Juridica had ceased making new investments and was liquidated a few years later. The immediate catalyst for the investor losses was Juridica’s sudden announcement that it would take a total loss on its largest asset, a price-fixing antitrust lawsuit it had previously touted as a potential billion-dollar recovery. The asset, which Juridica had previously recorded at $30 million on a fair value basis, had apparently become worthless. As explained in the case study, Juridica’s unraveling is not a story of fraud. Still, the episode demonstrates the high degree of discretion LFC management has in determining asset marks and the credulousness of both retail and institutional investors concerning those marks.

The second case study recounts the 2019 “short attack” mounted by hedge fund Muddy Waters Research LLC (Muddy Waters) against Burford Capital, Ltd. (Burford), the largest LFC by any metric then and now. This episode illustrates how opaque LFC accounts can undermine the market integrity objective of securities law. Specifically, it presents a (possible) case of a strategic effort to manipulate the market for an LFC’s stock by sowing seeds of doubt about the accuracy of the company’s fair value marks. In a published report, Muddy Waters highlighted the subjective nature of Burford’s fair value marks, comparing the company to Enron, the posterchild for modern corporate accounting fraud.9See Muddy Waters Capital LLC, MW is Short Burford Capital Ltd. (2019), https://d.muddywatersresearch.com/tou/?redirect=/content/uploads/2019/08/MW_BUR_08072019.pdf [perma.cc/R829-MWYF] [hereinafter Muddy Waters Burford Report]. The Muddy Waters report precipitated steep declines in the market prices of Burford stock and bonds, wiping fifty percent off the company’s market capitalization in a single day.10See Myles McCormick, Muddy Waters v Burford Capital – The Claims and Defence, Fin. Times (Aug. 8, 2019), https://www.ft.com/content/d06665de-b9e4-11e9-96bd-8e884d3ea203.

Only the future development of Burford’s portfolio will deliver the final verdict on whether the substance of this short attack was well-founded, as some of Muddy Waters’s past calls have been, or outright market manipulation, a term that some believe best describes Muddy Waters’s general approach to capital markets.11See Evan Hughes, The Man Who Moves Markets, The Atlantic (Feb. 2, 2023), https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2023/03/wall-street-muddy-waters-activist-short-sellers-tesla-gamestop/672774/ [https://perma.cc/C6FH-HZXP]. (It bears mentioning that Muddy Waters made a handsome profit by selling Burford stock short just prior to publishing the report).12See Michael O’Dwyer & Harriet Russell, Muddy Waters Boss Carson Block Dismisses Burford Capital’s Response to Short-Selling Attack as “Exactly by the Playbook”, The Telegraph (Aug. 9, 2019, 7:51 PM), https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2019/08/09/muddy-waters-boss-carson-block-dismisses-burford-capitals-response/ [https://perma.cc/6P5W-FC9A]. The fact that, even today, despite the wild gyrations in the market for Burford securities, this uncertainty persists, is evidence of the enduring and structural vulnerability of the sector to market manipulation.

This heightened potential for market manipulation raises obvious investor protection concerns, but its implications are broader. If LFCs present a structural risk of market manipulation, the first-order consequence to be expected is reduced access to public capital markets and lower overall capital inflows to the asset class. Second-order costs include higher bid-ask spreads for the sector, which can spread to other classes of new and existing securities, result in lower trading volumes, and ultimately feed into higher costs of capital and lower returns on investment in the litigation finance sector and neighboring alternative asset classes. In theory, these problems could even lead to less fixed capital spending and economic activity in other unrelated sectors.13See discussion infra Part III.

As the litigation finance industry grows, so too will the salience of these problems, intensifying the urgency of reform. Over the past decade, four LFCs have listed their shares on stock exchanges in the United States, the U.K., and Australia: Burford, Omni Bridgeway Ltd., Litigation Capital Management Ltd. (LCM), and Manolete Partners PLC (Manolete).14As mentioned above, a fifth LFC, Juridica, was publicly traded from 2007 until its 2018 liquidation. Today, the aggregate market capitalization of these companies approaches $3 billion.15As of April 26, 2023, the combined market capitalization of Burford Capital (.2 billion), Manolete (1 million), LCM (1 million), and Omni Bridgeway (3 million) was .9 billion. See infra notes 53-55 and accompanying text (introducing these publicly traded LFCs). We should expect more LFCs to look to public markets to meet their capital needs in this rapidly expanding sector. This Article presents not only the initial diagnosis of the problem, but also a framework for reform.

The Article advances six reform proposals, drawing attention to their respective advantages and disadvantages. Four of these proposals are more promising than the others: (1) mandatory direct involvement of external claims valuers in the production and verification of fair value marks; (2) greater deployment of claims valuation expertise in the context of the audit (either external or in-house audit expertise); (3) mandatory disclosure of portfolio-wide sensitivity analysis of the fair valuation marks; and (4) mandatory disclosure of details concerning material litigation assets with accompanying changes to the privilege waiver rules. The first three of these are not only promising, but they are also feasible; efforts to implement the fourth proposal should expect greater headwinds. Two other reform ideas—requiring independent valuation committees for publicly traded LFC boards and promoting markets for litigation assets—are also considered but are likely to be of limited effectiveness, at least in the near term.

Part II introduces the litigation finance industry, focusing on the basic value proposition of litigation finance transactions and describing the sector’s tremendous growth potential. Part II also introduces the publicly traded LFCs and outlines their motivations for accessing public capital markets. Next, Part III explains that the two fundamental objectives of modern securities law and regulation systems are investor protection and market integrity. Part III makes the preliminary case that publicly traded LFCs pose special threats to these objectives on account of the intrinsic opacity of their accounts and the significant discretion management deploys in their preparation and presentation.

Part IV guides the reader through the labyrinthine fair value accounting regime applicable to companies like LFCs that hold large amounts of opaque financial assets. Part IV also explains why the two LFCs adopting fair value accounting and therefore using internal valuation models (Burford and Manolete) are probably correct in determining that they are required to do so. It describes in detail how they implement those rules in practice. If Parts III and IV articulate the fundamental problem, Part V explains why legitimate concerns over privilege waiver prevent securities law from deploying its usual regulatory technology (i.e., more disclosure) as a corrective device. Part VI transitions from the abstract accounting, legal ethics, and evidentiary rules to the conundrum in its practical realities by presenting the Juridica and the Muddy-Watters-versus-Burford case studies. Part VII explores possible reforms, focusing on their respective advantages, disadvantages, and implementation challenges. Part VIII concludes.

II. Introducing the Litigation Finance Industry

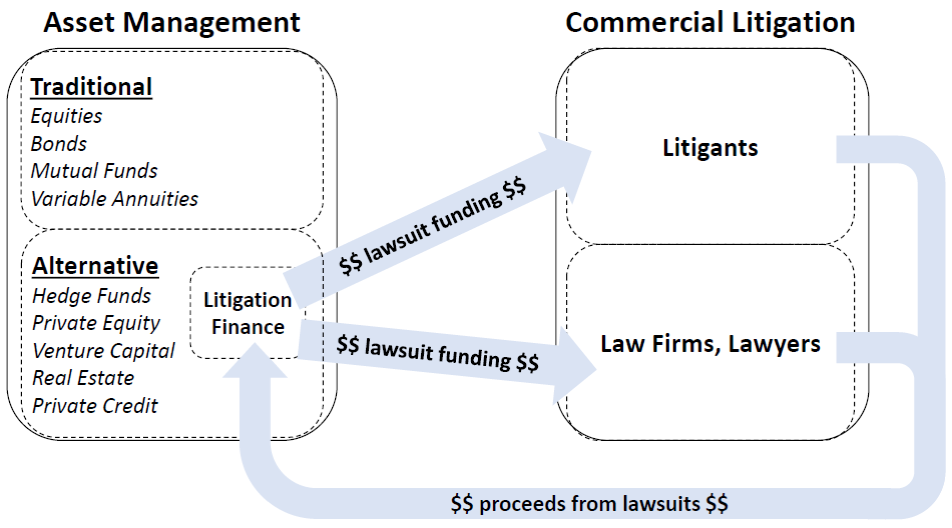

Described in the broadest terms possible, LFCs provide financing for law firms and litigants to pursue costly litigation in exchange for a direct or indirect share in the economic proceeds of the litigation. The litigation finance industry is a rapidly growing sector within the broader alternative investment sector, itself part of a broader investment management industry.16See Thomas Healey, Michael B. McDonald & Thea S. Haley, Litigation Finance Investing: Alternative Investment Returns in the Presence of Information Asymmetry, J. Alt. Inv., Spring 2022, at 110. LFCs thus link together the commercial litigation world with the asset management world. Figure 1 below shows this relationship, with the provisos that (1) the lists of types of asset managers is illustrative and not exhaustive, and (2) LFCs and other alternative asset managers are an overlapping category, as many diversified alternative asset managers are also increasingly deploying capital in litigation finance markets.17See Steinitz, Follow the Money?, supra note 1, at 1075 (“This market in legal claims has attracted specialist firms, private equity, hedge funds, wealthy individuals, the public (through crowdfunding platforms), and sovereign wealth funds, among others, who are looking for high-risk high-reward investments . . . .”).

Figure 1

Figure 1

This Part will introduce the basic features of the litigation finance world. First, the basic value proposition of litigation finance is introduced: the inter-temporal management of a particular type of legal-financial risk. The second section provides a brief description of the sector’s current market conditions, focusing on the present size of the market and the potential for future growth in the coming years. The third section introduces publicly traded LFCs, highlighting both their motivations for going public and previewing the dangers that arise when they do so.

A. The Basic Value Proposition of Litigation Finance

Litigation finance refers to the outside, usually non-recourse,18Non-recourse lending refers to extensions of credit in which the recourse of the creditor (in this context, the LFC) is limited to the collateral which secures the loan (in this context, a portion of the proceeds of the lawsuit). See Howard Ruda, Asset Based Financing: A Transactional Guide § 1.01[3] (2021). If the lawsuit fails to produce proceeds, the LFC has no claim against the litigant or law firm that received the funding. funding of lawsuits by third parties for a profit.19See Maya Steinitz & Abigail C. Field, A Model Litigation Finance Contract, 99 Iowa L. Rev. 711, 713 (2014); Alex Lempiner & Simon Walsh, Woodsford Litig. Funding, A Practical Guide to Litigation Funding (2018); John Pierce & David Burnett, The Emerging Market for Litigation Funding, The Hedge Fund J. (June 2013), https://thehedgefundjournal.com/the-emerging-market-for-litigation-funding/ [https://perma.cc/WD5T-47XE]; Am. Bar Ass’n Comm’n on Ethics, White Paper on Alternative Litigation Finance 1 (2011) https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/ethics_2020/20111019_draft_alf_white_paper_posting.authcheckdam.pdf [https://perma.cc/NAY4-J2PT]. In its simplest terms, the basic market opportunity the LFCs exploit results from the temporal mismatch between litigation-related events and litigation-related payouts. Litigation-related events consist of the actionable conduct, the decision to pursue a legal dispute, the pleading stage, dispositive motions, trial, appeal, and so forth. Litigation-related payouts consist of settlements, judgments, and collections. This mismatch creates both risks and opportunity costs. From the litigation finance perspective, litigation is “just a process of moving money from one person to another. Just like any receivable, it has value.”20Elliot Wilson, Capital Markets: Litigation Funding Finds Its Feet, Euromoney (Dec. 14, 2020), https://www.euromoney.com/article/27vppy0icqztjnbtg6ww0/capital-markets/capital-markets-litigation-funding-finds-its-feet [https://perma.cc/GQE9-S2R8] (quoting Christopher Bogart, Burford’s chief executive officer). The value proposition that LFCs offer is that they stabilize the inter-temporal risk exposure of litigation-related receivables—i.e., the risk inherent in bringing lawsuits with the expectation of an uncertain payout at an uncertain future date.

For example, a plaintiff might calculate that the expected payout, net of expected costs, from a patent infringement claim is $20 million, reflecting its estimation that the claim has a 50% likelihood of success on the merits, in which case it would be entitled to a net payout of $40 million. In the meantime, however, both the plaintiff and its law firm(s) incur direct and indirect expenses in connection with the lawsuit; in other words, those “costs” that we netted out in the first sentence still exist. Direct expenses include legal fees, expert witness fees, court fees, investigative costs, and fees of other specialized consultants brought into the litigation team, such as accountants, bankers, and doctors. Indirect expenses include the distraction to management, which will be diverted from their primary business responsibilities in the case of large-dollar lawsuits. Also, the plaintiff will incur opportunity costs insofar as the temporal mismatch means that the expected payout will materialize months or years later; in the meantime, the plaintiff is not yet in possession of its expected payout and is unable to invest the expected proceeds in the business.21For instance, Burford recently developed a hybrid debt-equity financing that helped a venture backed tech company embroiled in a protracted patent and trade secret case against an industry giant. Burford touted the fact that the approach “reduced the company’s litigation-related operating expenses to zero and increased its cash on-hand for growth . . . .” Burford Capital, Ltd., 2021 Burford Client Update & 2020 Year in Review 9 (2021), https://www.burfordcapital.com/media/2075/2021-burford-client-update-and-year-in-review.pdf?utm_source=blog&utm_medium=button&utm_campaign=2021clientupdate&utm_content=landing [https://perma.cc/P3Q2-B3PA].

Absent third-party financing, the plaintiff finds itself in a bilateral monopoly game. A bilateral monopoly describes a market scenario with one buyer and one seller. Assuming there is a positive available surplus, it is in the interests of both parties to engage in a trade, but they can trade only with the other party.22See Geoffrey P. Miller, Some Agency Problems in Settlement, 16 J. Legal Stud. 189, 193 (1987) (specifying that the incentives to trade depend on there being a surplus in the form of a positive settlement range). In this hypothetical world without external financing, a plaintiff can only sell its claim to the defendant,23See Geoffrey P. Miller, Commentary, On the Costs of Civil Justice, 80 Tex. L. Rev. 2115, 2115 (2002) (“A lawsuit is essentially a sale. The defendant buys a valuable asset from the plaintiff, in the form of a release of claims if the case is settled, or a verdict with res judicata effect if the case goes to a verdict.”). which quite frequently also has a greater ability to bear the risk of loss during the pendency of the litigation.24See Molot, supra note 1, at 70 (“Where a lawsuit pits a one-time plaintiff against a repeat-player defendant, we would thus expect the imbalance in the parties’ risk preferences to favor the defendant and produce settlements below the mean [expected] damages award.”). Accounting rules further complicate incentives for publicly traded commercial plaintiffs; they will recognize expenses associated with pursuing the lawsuit as short-term operating expenses, with no corresponding revenue increase during the pendency of the matter.25See Bob Craig, Daniel Ryan & Larry Tedesco, Litigation Finance 101—What You Need to Know, ThinkSet (Nov. 4, 2018), https://thinksetmag.com/issue-6/litigation-finance-101 [https://perma.cc/3YHP-MFE4]. The expense drain can distort the picture of the company’s operational realities. Complicating matters further, even when the litigation results in a payout, the economic impact is reported as non-recurring income and, therefore, liable to be disregarded by investors.26See id.

Further, the law firms that represent the plaintiff usually assume a similar portfolio of risks. Most lawyers in the United States represent plaintiffs on a contingency basis—that is, they are paid out of the lawsuit’s proceeds.27See Stephen Daniels & Joanne Martin, The Texas Two-Step: Evidence on the Link Between Damage Caps and Access to the Civil Justice System, 55 DePaul L. Rev. 635, 648 (2006). While contingency fee representation is relatively less prevalent in the business litigation context, it is becoming more common there as well, owing to pressures from corporate clients to reduce corporate legal spending.28See Dan Roe, Demand for Contingency Fees in Business Litigation Grows Amid Pandemic, Law.com (Nov. 20, 2020) https://www.law.com/2020/11/30/demand-for-contingency-fees-in-business-litigation-grows-amid-pandemic/ [https://perma.cc/53RL-7SCF]. The contingency fee arrangement operates as a risk-transfer mechanism by which the litigant client offloads some of its risk onto the law firm, which, because of its repeat-player status and professional expertise, is thought to be better positioned to bear the risk. Before the lawsuit generates any proceeds, the law firm must pay its expenses—employee salaries, insurance premiums, utility payments, lease payments, and anticipatory distributions of profits to partners (where appropriate). In other words, law firms face relatively high working capital demands and a deficit of patient risk capital to carry multi-year matters through to conclusion.

Hence the basic litigation finance value proposition: LFCs provide the longer-term capital required to bring the lawsuit to a successful conclusion. The funding can be directly provided to the litigants or their law firms. Investments by LFCs can be structured in multiple ways. Broadly speaking, however, corporate litigants usually obtain financing by agreeing to provide a return to the LFC tied to the success of the underlying claim or portfolio of claims, whether in the form of a right to a specified percentage of the payout,29Traditional prohibitions on champerty and maintenance of claims, which historically prevented third-party funders from sharing in claim recoveries, have been abandoned in many states, and, moreover, generally do not apply to business claims. See 14 Am. Juris. 2d Champerty, Maintenance, Etc. §§ 1–15 (2021); Jay Greenberg, Why Litigation Finance Transformed in the 2010s, and What 2030 Might Bring, The Recorder (Cal.) (Mar. 16, 2020); Michael K. Velchik & Jeffery Y. Zhang, Islands of Litigation Finance, 24 Stan. J. L. Bus. & Fin. 1 (2019); Anthony J. Sebok, The Inauthentic Claim, 64 Vand. L. Rev. 61 (2011) [hereinafter Sebok, Inauthentic Claim]. or a more bespoke structured contractual arrangement. These arrangements are either undertaken as on-balance-sheet investments by the LFC or as off-balance-sheet investments where the LFC manages private investment funds on which it earns a customary management fee.30When managing private funds, the LFC essentially is acting as a private equity fund manager, soliciting funds from investors, and investing them in litigation assets on behalf of the investors.

On the other hand, law firms currently face restrictions on sharing fees with nonlawyers, which complicates efforts to provide litigation finance to law firms.31See Steinitz, Whose Claim?, supra note 3, at 1291–92 (explaining chilling effect on litigation finance industry of the prohibition on fee splitting); Model Rules of Pro. Conduct r. 5.4(a) (Am. Bar Ass’n 2020) (“A lawyer or law firm shall not share legal fees with a nonlawyer . . . .”). Frequently, LFCs maneuver around the prohibition on fee sharing by simply providing debt-like finance to law firms on a nonrecourse basis, with the firm agreeing to pay to the funder a contractually-specified return, secured by the law firm’s contingency-fee receivables for a financed case or portfolio of cases.32See Joan C. Rogers, Litigation Funding on Rise in Big Cases, Panel Says, Bloomberg L. (Mar. 23, 2017) https://news.bloomberglaw.com/us-law-week/litigation-funding-on-rise-in-big-cases-panel-says [https://perma.cc/2L28-PPU9]. As a general matter, lawyers face no professional restrictions on borrowing money. A recent trend to liberalize fee-sharing rules augurs greater acceptance of finance arrangements involving LFCs sharing in contingent legal fees directly.33For example, the District of Columbia and Arizona have both formally abrogated the ABA’s Model Rule of Professional Conduct 5.4, which sets forth the prohibition on fee sharing. Relatedly, courts are increasingly agreeing to enforce such financing arrangements. See, e.g., Hamilton Capital VII, LLC v. Khorrami, LLP, No. 650791/2015 22 N.Y.S.3d 137, 2015 WL 4920281, at *6 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. Aug. 17, 2015) (enforcing funding contract pursuant to which LFC advanced funds to law firm in exchange for a percentage of the law firm’s gross revenues, with the latter obligation secured by the firm’s accounts receivable, and noting that such an arrangement “helps provide victims their day in court”); Counsel Fin. Servs., LLC v. Leibowitz, No. 13-12-00103-CV, 2013 Tex. App. LEXIS 9252, at *28 (Tex. App. July 25, 2013) (“[T]here is a significant difference between sharing legal fees with a non-lawyer and paying a debt with legal fees.”). The influential New York City Bar Association (NYBCA) formed a working group to study litigation finance, which in 2020 recommended that the NYCBA abrogate its Formal Ethics Opinion 2018-5, which had concluded that prototypical litigation finance arrangements would violate Rule 5.4. See Working Group on Litigation Funding, N.Y.C. Bar Ass’n, Report to the President 20–24 (2020) http://documents.nycbar.org/files/Report_to_the_President_by_Litigation_Funding_Working_Group.pdf [https://perma.cc/7KG2-AVB2]; N.Y.C Bar Ass’n Comm. on Pro. Ethics, Formal Op. 2018-5 (2018) https://s3.amazonaws.com/documents.nycbar.org/files/2018416-Litigation_Funding.pdf [https://perma.cc/H2U6-JP9C].

This description summarizes the financial and economic logic of litigation finance transactions. It bears note that many LFCs supplement and diversify their business by engaging in adjacent, related business lines such as asset recovery, proprietary strategic litigation seeking to obtain rulings favorable to the litigation finance industry, and financing/monetization of post-settlement litigation receivables.34See Burford Capital Ltd., Annual Report 10-11 (Form 20-F) (Mar. 24, 2021) [hereinafter Burford 2020 Annual Report].

B. A Snapshot of the Industry Today

From its modest origins in Australia and the United Kingdom in the 2000s, to its slow-but-steady expansion in the United States in the subsequent decades,35See Wilson, supra note 20 (describing litigation finance as “growing at a steady pace without ever quite catching fire”); Michele DeStefano, Nonlawyers Influencing Lawyers: Too Many Cooks in the Kitchen of Stone Soup?, 80 Fordham L. Rev. 2791, 2819–22 (2012) (recounting origins in U.K. and Australia). litigation finance has gradually emerged as a transformational phenomenon for the civil justice system.36See Steinitz, Follow the Money?, supra note 1, at 1075 (characterizing litigation finance as “likely the most important development in civil justice of our time”); Sahani, supra note 3, at 392 n.10 (referring to litigation finance as a “paradigm shift in dispute resolution”). The sector is growing, both in terms of the number of participants and revenue. One litigation finance brokerage currently estimates that litigation funders have over $11 billion either currently invested or ready to invest in U.S. commercial litigation.37Jack Newsham, The Power Players of the Booming Litigation Finance Industry, Business Insider (May 26, 2021, 7:48 AM) https://www.businessinsider.com/power-players-of-the-booming-litigation-finance-industry-2021-5 [https://perma.cc/9HNQ-JNZW].

Furthermore, there is unanimous agreement that there is significant potential for the market to grow,38See Annie Pavia, Are Boom Times Ahead for Litigation Finance?, Bloomberg Law (Nov. 13, 2022, 9:01 P.M.) https://news.bloomberglaw.com/bloomberg-law-analysis/analysis-are-boom-times-ahead-for-litigation-finance [https://perma.cc/4WNT-HKAN]. especially in the United States.39Litigation funders attribute the relatively low degree of penetration in the U.S. market in large part to legal and business culture, as well as the durability of legal restrictions on maintenance and champerty that complicate efforts for non-lawyer third-parties to finance or own interests in legal claims. The total addressable market for litigation finance is difficult to estimate. In the first place, there are two distinct sources of revenue: claims on lawsuit proceeds (in the case of funded litigants) and claims on law firm revenues (in the case of funded law firms). In 2019, IMF Bentham, then a large publicly traded LFC,40IMF Bentham Ltd. and Omni Bridgeway Holdings B.V. merged in November 2019, and in February 2020 the combined entity changed its name to Omni Bridgeway Ltd. John Freund, IMF Bentham to Become Omni Bridgeway, Litig. Fin. J. (Feb. 14, 2020) https://litigationfinancejournal.com/imf-bentham-to-become-omni-bridgeway/ [https://perma.cc/5S2C-5C4G]. attracted attention when it estimated in its Annual Report that the total addressable market for litigation finance in the United States was $85 billion.41IMF Bentham Ltd., Annual Report 2019, at 32 (2020). This estimate was derived from the share of litigation expenses going to plaintiffs’ lawyers, apparently on the theory that that entire amount could become financed.42See id. at 13. This estimate is both conservative and exaggerated. It is conservative because it fails to capture financeable defendant opportunities43See Jonathan T. Molot, A Market in Litigation Risk, 76 U. Chi. L. Rev. 367, 377–80 (2009) (proposing that corporate defendants use litigation finance as source of capital to absorb litigation risk after the filing of a lawsuit). and, much more importantly, the direct monetization of claims by business litigants themselves.44See Dai Wai Chin Feman & Sean Thompson, Claim Monetization: A Lesser Known Use of Litigation Finance, Corp. Counsel (Feb. 14, 2019) (https://www.law.com/corpcounsel/2019/02/14/claim-monetization-a-lesser-known-use-of-litigation-finance/). On the other hand, it is exaggerated insofar as it is predicated on the industry maintaining a beneficial financial interest in all plaintiff attorneys’ fees, which would hardly be advisable, if it were even possible at all.45Other estimates based on law firm revenues hover in the same range. See Brian Baker, In Low-Yield Environment, Litigation Finance Booms, MarketWatch (Aug. 21, 2018, 10:59 AM) https://www.marketwatch.com/story/in-low-yield-environment-litigation-finance-booms-2018-08-17 [https://perma.cc/RC74-ZBYD] (reporting –100 billion estimate of Cindy Chen Delano, a litigation finance professional). While the precise scope of the market opportunity is uncertain, it is clear that litigation finance will remain a fixture, with significant room to grow.

In the meantime, Burford, the largest LFC by any metric, already counts 94 of the “AmLaw 100” law firms, and 90 of the 100 largest global law firms, as its clients.46See Burford 2020 Annual Report, supra note 34, at ix. The 2008–2009 recession provided a special impetus to the law firm finance market, which saw many law firms lose access to bank credit and face increased pressure from corporate clients to transition away from hourly billing as the predominant modality of attorney compensation.47See Eva Shang & Robbie Li, Insight: Litigation Finance Could Be a Lifeline During Pandemic, Bloomberg L. (May 26, 2020, 4:00 AM) https://news.bloomberglaw.com/us-law-week/insights-litigation-finance-could-be-a-lifeline-during-pandemic [https://perma.cc/2CY3-FDAM]. Well aware of the global growth potential, the industry founded its own worldwide trade association in September of last year: the International Legal Finance Association (ILFA).48See Sara Merken, Litigation Finance Firms Join Forces to Counter Skeptics in Lobbying, PR Push, Westlaw News (Sept. 8, 2020, 6:30 PM) https://www.reuters.com/article/litigation-finance-firms-join-forces-to/litigation-finance-firms-join-forces-to-counter-skeptics-in-lobbying-pr-push-idUSL1N2G528Y [https://perma.cc/84CS-VMT7]. Even earlier, industry participants had formed jurisdiction-specific trade associations, such as the American Legal Finance Association and Association of Litigation Funders in the United Kingdom.

So much for the demand side. The supply side, consisting of investment fund flows, is in plentiful supply as well, with even traditionally conservative investment institutions like university endowments starting to invest.49See Greenberg, supra note 29, at 2 (mentioning investments by the University of Michigan and Harvard University, which maintain two of the largest endowment funds in the world). First, the low-rate environment has increased investor appetite for non-traditional investments. In this respect, the flow of savings into litigation finance investments is of a piece with investment flows to cryptocurrency, real estate, and commodities. A second factor stoking demand for litigation finance investment is the relatively low correlation of litigation finance returns with the broader economy, which offers investors diversification benefits.50See J.B. Heaton, The Siren Song of Litigation Funding 9 Mich. Bus. & Entrepreneurial L. Rev. 139, 143–44 (2019). Litigation finance returns are a function of underwriting practices and court timelines rather than consumer spending, commodity prices, corporate investment, etc.51See Burford Capital: Class War Capitalist, Fin. Times (Aug. 28, 2017), https://www.ft.com/content/cc46e274-54c6-11e7-9fed-c19e2700005f [https://perma.cc/6MH4-E5W5].

C. Publicly Traded LFCs

Currently, more than forty specialized LFCs operate in the United States.52See Westfleet Advisors, The Westfleet Insider: 2020 Litigation Finance Market Report 4 (2020) (“The number of litigation funders active in the U.S. market grew from 41 in 2019 to 46 in 2020, according to our research.”); Andrew Langhoff, An Overview of Litigation Finance Brokerage in the USA, in Chambers Litigation Support 2020: Leading Litigation Professionals Worldwide 60, 60 (2020) https://complexdiscovery.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Chambers-Litigation-Support-2020.pdf [https://perma.cc/6SGQ-BX8L]. The worldwide number is undoubtedly greater. Yet, only four of these companies are publicly traded worldwide.53Another LFC, Vannin Capital, abandoned a contemplated public listing in 2018 following an unfavorable development in its own portfolio and sector-wide valuation concerns. See Kate Beioley, Vannin Capital Sold to Fortress a Year After Abandoning IPO, Fin. Times (Sept. 6, 2019) https://www.ft.com/content/1288d980-d0ae-11e9-b018-ca4456540ea6 [https://perma.cc/AT7L-UHB7]. In descending order of current market capitalization, these firms are Burford, Omni Bridgeway, Manolete, and LCM. Burford is incorporated in Guernsey (a small island state in the English Channel that serves as a popular jurisdiction of incorporation) and is listed on the Alternative Investment Market (AIM)54Burford initially listed on the AIM in 2009. Burford 2020 Annual Report, supra note 34, at 4. of the London Stock Exchange (LSE) and, as of October 2020, the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) as well. Omni Bridgeway and LCM are traded on the Australian Stock Exchange; the latter is also traded on the AIM. Manolete is traded on the AIM only. A fifth LFC, Juridica Investments Ltd. (Juridica), was traded on the AIM from 2009 until it was delisted in December 2018.55See discussion infra Part VI.A (discussing Juridica’s failure at length). Together, these four public companies have an aggregate market capitalization as of September 2022 of just under $3 billion.

As with any industry, the public-private distinction has significant implications for how LFCs conduct business. Most obviously, publicly traded LFCs must comply with the periodic and episodic reporting regime imposed by the securities laws. Less straightforward, but equally as important, are the governance implications for an LFC transitioning from a fund model to a public company model. Private investment funds in the private equity, venture capital, and hedge fund sectors operate in an environment where transparency and disclosure expectations are lowered, investors are sophisticated or wealthy (or both), and trust is the predominant cultural norm.

By contrast, investors in public companies expect much more detailed financial and non-financial disclosures than investors in private funds. Moreover, public companies must accommodate the expectations of public market investors for earnings reporting and guidance. This, in turn, affects corporate governance practices. As the saying goes, “if you show me what you count, I’ll show you what counts.” Numbers and accounting practices play a constitutive role; they not only reflect the social world but also help shape it, bringing into existence new practices and routines.56See Theodore M. Porter, Making Things Quantitative, in Accounting and Science: Natural Inquiry and Commercial Reason 36, 46 (Michael Power ed., 1994) (“Quantification has an important constructive role. With numbers one can often make new things, or at least transform old ones.”). Firms that are not normally in the practice of reporting periodic—and frequently asynchronous, when compared to their investment time horizon—earnings must suddenly not only produce that information, but devote internal resources to deliberating on and projecting future earnings. When Burford, Omni Bridgeway, LCM, and Manolete decided to go public, they opted into a new financial reporting regime and assumed a cluster of anticipated and unanticipated governance implications.

What drives management to take LFCs public? For the most part, the motivations driving LFC managers to list their companies’ shares are the standard set of considerations for all public companies. Most obviously, listed companies have ready access to debt and equity capital.57 David A. Westenberg, Initial Public Offerings: A Practical Guide to Going Public § 1:2.1, at 1–4 (2d ed. 2012). As noted earlier, the sector is growing and requires capital to fund this growth.58See supra Part II.B. In the LFC context, debt capital tends to fund growth,59See, e.g., Burford 2020 Annual Report, supra note 34, at 66. and equity capital, being more patient, makes LFCs more resilient to potential liquidity mismatches that pose a threat to all financial institutions that lend long.60See Manolete Partners PLC, Annual Report 2020 15 (2021) [hereinafter Manolete 2020 Annual Report] (“The IPO . . . has given us the financial firepower to take on a higher number of cases and larger cases, without fear of portfolio concentration risk.”); Nick Rowles-Davies, Why Litigation Finance Is Suited to Public Markets, Litig. Fin. J. (Aug. 28, 2019), https://litigationfinancejournal.com/litigation-finance-suited-public-markets/ [https://perma.cc/2D8Y-XJ8U]. By going public, an LFC not only secures equity capital, but it also significantly facilitates the public sale of debt.61If a company is already subject to the securities law reporting regime on account of its equity securities being listed, it can access public debt capital markets without incurring any significant incremental compliance costs. See 15 U.S.C. § 78m (conditioning reporting company status on having a class of securities registered on a national securities exchange). Further, publicly traded LFCs can freely use their stock as acquisition currency,62Stock is used as acquisition currency when a public company provides newly issued stock to the stockholders of a target company as full or partial consideration for the acquisition. as Burford did in 2016 when it acquired litigation finance fund manager Gerchen Keller.63See Alison Frankel, Burford, Gerchen Keller to Merge: Turning Point for Litigation Funding?, Reuters (Dec. 14, 2016) https://www.reuters.com/article/us-otc-burford/burford-gerchen-keller-to-merge-turning-point-for-litigation-funding-idUSKBN1432S4. [https://perma.cc/UUJ2-SLGP]. In this respect, public company status facilitates consolidation and revenue diversification. And publicly traded LFCs are more readily able to compensate management by issuing stock, stock options, and other securities, a practice that is thought to align the microeconomic incentives of managers and other security holders.64See, e.g., Lucian Arye Bebchuk & Jesse M. Fried, Paying for Long-Term Performance, 158 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1915 (2010); Lucian Arye Bebchuk & Jesse M. Fried, Executive Compensation as an Agency Problem, 17 J. Econ. Persp. 71 (2003).

An additional motivating factor applies with particular force in the litigation finance industry and provides an entry point into the problem considered in this essay. Specifically, some LFCs have touted the corporate governance benefits flowing from the added transparency that public company status entails. To be sure, securities market professionals have long touted the “branding” and signaling benefits that a company enjoys, particularly if it lists on a reputable exchange with exacting corporate governance listing standards.65See Onnig H. Dombalagian, Exchanges, Listless?: The Disintermediation of the Listing Function, 50 Wake Forest L. Rev. 579, 581–83 (2015). However, this general objective assumes heightened importance in the LFC context. In the words of Nick Rowles-Davies, a former Burford executive and current LCM executive vice chairman:

Being listed on any stock exchange ensures a level of regulation and transparency that the private markets do not. . . . As a constituent of a public market, there is pressure to ensure that standards of corporate governance are upheld. Natural checks exist to hold companies to account in the form of selling investors, analysts publishing negative research, and, at the most extreme level, activists or short sellers publicly targeting companies.66Rowles-Davies, supra note 60.

Thus, the stock exchange as an institution imposes “natural checks” on possible self-serving behavior on the part of the managers. Yet, this governance story is complicated by the fact that company management—now flush with liquid, tradable securities—has heightened incentives to engage in stock price and earnings management. That is, if stock prices are evaluated in large part by the use of relative valuation techniques like price-to-earnings (PE) ratios,67See Aswath Damodaran, Investment Valuation 468 (3d ed. 2012) (“Earnings multiples remain the most commonly used measures of relative value.”). the incentive exists for management to, as Carson Block—head of the short-only hedge fund Muddy Waters—puts it, “juice the earnings and make up the E.”68Muddy Waters’ Carson Block on Burford Capital Short (CNBC television broadcast Dec. 13, 2019), https://www.cnbc.com/video/2019/12/13/muddy-waters-carson-block-on-burford-capital-short.html [https://perma.cc/2UPF-57KK].

Public company status, therefore, is characterized by a tension. On the one hand, the open spigot of liquid company securities to management heightens the temptation to engage in unethical behavior by artificially inflating earnings and other metrics. On the other hand, as Rowles-Davies emphasizes, public companies provide publicity and transparency and invite scrutiny from investment professionals—including activists and short sellers like Muddy Waters.69See Rowles-Davies, supra note 60.

To a significant degree, this tension is a general structural property of public securities markets; it is observable with all public companies and across all industries and sectors. However, the main argument here is that the intrinsic opacity of LFC financial accounting and reporting practices significantly destabilizes and problematizes the tension, undermining in the process the two main objectives of disclosure-based securities regulation.

III. Publicly Traded LFCs Pose Threats to the

Two Pillars of Securities Regulation

The two main objectives of securities regulation are protecting investors and promoting fair, efficient, and transparent markets.70See Int’l Org. of Sec. Comm’ns, supra note 5, at 3. Efficient capital formation is sometimes added as a third objective, although it is usually thought to be derivative of these investor protection and market integrity grundnorms.71Mainstream economics assumes that promoting fair and efficient securities markets will result in roughly efficient capital formation. See Merritt B. Fox & Kevin S. Haeberle, Evaluating Stock-Trading Practices and Their Regulation, 42 J. Corp. L. 897–903 (2017). Post-Keynesian economists dispute this basic premise. See L. Randall Wray & Eric Tymoigne, Macroeconomics Meets Hyman P. Minsky: The Financial Theory of Investment, in Macroeconomic Theory and Macroeconomic Pedagogy 234 (Giuseppe Fontana & Mark Setterfield eds., 2009). More recently, systemic risk is sometimes invoked as an additional objective of the securities laws, although this desideratum has been a shared responsibility for all financial regulators for at least a decade, and is not properly thought of as the core bailiwick of securities regulators. The two central themes, then, of securities regulation over the past century have been investor protection and market integrity. On account of the opacity of their assets, publicly traded LFCs pose threats to both of these objectives.

As discussed in greater length below, litigation finance assets are difficult to value before they result in cash settlements or court judgments. There is no obvious method for how to account for a litigation asset that was purchased for $5 million and could possibly result in recovery scenarios ranging from $0 to $40 million. This uncertainty is even more pronounced when reasonable lawyers and litigation funders disagree about the likelihood of the total-loss and extraordinary-recovery scenarios, and all the alternative scenarios in between. And yet, from an investor’s perspective, the LFC’s enterprise value depends entirely on its ability to generate returns from these opaque assets.

The accounting profession responds to uncertainty of this sort with so-called fair value accounting, which—as discussed in greater detail below—requires reporting entities to report, or “mark,” the values of assets like these according to internal valuation models. The use of such a model entails so-called model risk, which is helpfully defined and discussed by the Federal Reserve in terms that are generalizable even beyond the banking context:

The use of models invariably presents model risk, which is the potential for adverse consequences from decisions based on incorrect or misused model outputs and reports. . . . Model risk occurs primarily for two reasons: (1) a model may have fundamental errors and produce inaccurate outputs when viewed against its design objective and intended business uses; (2) a model may be used incorrectly or inappropriately or there may be a misunderstanding about its limitations and assumptions. Model risk increases with greater model complexity, higher uncertainty about inputs and assumptions, broader extent of use, and larger potential impact.72 Fed. Rsrv. Bd. of Governors, Supervision & Regul. Letter No. 11-7: Guidance on Model Risk Management (2011), https://www.federalreserve.gov/supervisionreg/srletters/sr1107.htm [https://perma.cc/9NPR-5R37].

Model risk, when defined in this manner, captures the strategic manipulation of well-designed models, the construction of poorly designed models, and the faulty implementation of all sorts of models. From the vantage point of securities regulation, the opacity and the accompanying model risk creates a twofold problem for the publicly traded LFC, which assumes heightened responsibilities when it comes to disclosure and transparency.

First, it undermines investor protection because the intrinsic opacity of LFC asset valuation complicates the detection of fraudulent or negligent financial reporting, which can lead to investor losses. These problems result from doctrinal considerations and the potential for the confusing presentation of results. As a doctrinal matter, the prevalence of fair value accounting practices among publicly traded LFCs neutralizes much of the accuracy-enhancing effects of securities law antifraud rules. The central feature of securities regulation is a non-waivable, credibly enforceable antifraud remedy that enhances the reliability of disclosure for all companies, leading to more accurate valuations and more efficient capital investment.73The classic expression of this view is Frank H. Easterbook & Daniel R. Fischel, The Economic Structure of Corporate Law 280–85 (1991). However, judicial insistence on proof of wrongful state of mind,74See Ernst & Ernst v. Hochfelder, 425 U.S. 185, 212 (1976) (clarifying that Rule 10b-5 plaintiffs must allege scienter—that is, a fraudulent intent on the part of defendants); James J. Park, Rule 10b-5 and the Rise of the Unjust Enrichment Principle, 60 Duke L.J. 345, 386–87 (2010) (speculating that the strictness of the scienter requirement might “create a divergence between Rule 10b-5 and its goal of reducing misstatements that distort the efficiency of the markets”). as well as case precedent restricting the application of the antifraud rules to opinion statements,75See Omnicare, Inc. v. Laborers Dist. Council Constr. Indus. Pension Fund, 575 U.S. 175, 190–91 (2015) (holding that opinion statements are actionable only where the speaker affirmatively disbelieves the matter as to which the speaker is stating their belief). attenuate the effectiveness of the antifraud regime as a corrective for the opacity of litigation finance accounts. After all, model risk captures good-faith (and therefore unactionable) errors in judgment, and all valuation models involve the use of inherently subjective and contestable assumptions that are, in an important sense, opinions.

More subtly, the public company financial reporting rules requiring periodic “fair value” estimates of asset values might also cause some retail investors to underappreciate the inherent discretion managers exercise in valuing assets—in good faith or otherwise—and thereby possibly overestimate the reliability of LFC financial statements. Sociologist Nicolas Rose notes that, in modern societies, “[n]umbers are resorted to in order to settle or diminish conflicts in a contested space of weak authority.”76 Nikolas Rose, Powers of Freedom: Reframing Political Thought 208 (1999). For Rose, the “power of a single figure” is “a rhetorical technique for ‘black boxing’—that is to say, rendering invisible and hence incontestable—the complex array of judgments and decisions that go into a . . . number.”77Id. (internal quotation marks omitted).

It is possible to view fair value accounting generally as a second-best solution to the problem of accounting for asset values in highly uncertain environments. Following Rose, there are only “weak authorities” on which to base valuations, so recourse to internal valuation models is arguably necessary. However, reliance on the internal models, which yield single point estimates of value, might in the process “black box” and obscure the complex and ineradicable uncertainty concerning the value of the marked assets. Nassim Taleb has written on this theme in the financial context: “Once on a page or on a computer screen . . . [a] projection takes on a life of its own, losing its vagueness . . . and becoming what philosophers call reified, invested with concreteness; it takes on a new life as a tangible object.”78 Nassim Nicholas Taleb, The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable 158 (2d ed. 2010). The prospect of undue investor credulousness leading to investor losses is also part of the investor protection problem regarding opaque assets.

Second, the structural opacity of the company’s valuation creates conditions ripe for market manipulation through strategies like so-called “short attacks” and “bear runs,” as some believe happened recently with Burford and the hedge fund Muddy Waters. The reference to market manipulation here, and throughout this paper, is intended to capture strategic attempts to create and profit from disjoints between the intrinsic value and the market price of a firm’s securities. What this definition perhaps lacks in specificity it compensates for in its capaciousness. Over a century ago, financial journalist Albert Atwood noted that manipulation “is more easily seen than defined,” but that it “almost invariably conveys the idea of artificiality.” 79 Albert W. Atwood, The Exchanges and Speculation, in 20 Modern business 253 (Joseph French Johnson ed., 1918) (emphasis added).

This notion of artificiality requires further elaboration. Two central meanings of “artificiality” should be distinguished. On the one hand, a price could be artificial in the sense that it results from artificial tinkering with perceptions and records of supply and demand—from falsely modifying the order flow out of which the price emerges, or is said to be passively “discovered” by market forces. For instance, a group of traders might manipulate a stock price by “spoofing” or “layering” non-bona fide buy orders that they intend to cancel, so as to give the false impression of a surge in demand for a security.80See Andrew Ceresney, Dir., Div. of Enf’t, U.S. Sec. & Exch. Comm’n, Market Structure Enforcement: Looking Back and Forward: Speech at SIFMA Compliance & Legal Society New York Regional Seminar (Nov. 2, 2015), https://www.sec.gov/news/speech/ceresney-speech-sifma-ny-regional-seminar.html [https://perma.cc/3KTL-468M]. On the other hand, a price could be artificial in the sense that it diverges from what would have been the price absent a flood of bona fide sell orders that were entered solely to affect the security’s market price, with no consideration of fundamental, intrinsic value of the security. An artificial price in this second, broader sense is a price that moves away from its previous level on account of strategic action on the part of the manipulator. It is this latter sense of artificiality that is intended to be captured by the capacious formulation of manipulation adopted here, which is sometimes referred to as “open-market manipulation.”81See Gina-Gail S. Fletcher, Legitimate Yet Manipulative: The Conundrum of Open-Market Manipulation, 68 Duke L.J. 479, 501 (2018); see also Maxwell K. Multer, Open-Market Manipulation Under SEC Rule 10b-5 and its Analogues: Inappropriate Distinctions, Judicial Disagreement and Case Study: FERC’s Anti-Manipulation Rule, 39 Sec. Reg. L.J. 97, 100 (2011).

The prohibition on market manipulation in American securities law has been interpreted by courts more restrictively, consistent with a strict interpretation of manipulation and artificiality requiring the stoking of false perceptions about actual supply and demand.82See, e.g., ATSI Communications, Inc. v. Shaar Fund, Ltd., 493 F.3d 87, 100 (2d Cir. 2007) (noting that actionable market manipulation is present only where “investors are misled to ‘believe that prices at which they purchase and sell securities are determined by the natural interplay of supply and demand, not rigged by manipulators’”); GFL Advantage Fund, Ltd. V. Colkitt, 272 F.3d 189, 211 (3d Cir. 2001) (observing that a plaintiff “must present evidence that [a defendant] engaged in some other type of deceptive behavior in conjunction with its short selling that either injected inaccurate information into the marketplace or created artificial demand for the securities”). As such, practices like short selling, even when accompanied by aggressive press publicity in the financial press, are legal absent exceptional circumstances.83See James D. Cox et al., Securities Regulation: Cases and Materials 750 (9th ed. 2020). In the European Union and the United Kingdom, the Market Abuse Regulation similarly focuses on supply and demand as its overarching principle.84See Commission Regulation 596/2014, art. 12, 2014 O.J. (L 173) 1, 30 (EU); see also Simmons & Simmons, Market Abuse Regime After Brexit (Dec. 1, 2021) https://www.simmons-simmons.com/en/publications/ck3syn2ankauk0b48d8k8hbzb/market-abuse-regime-after-brexit [https://perma.cc/TZF8-YHQA] (noting that post-Brexit U.K. market abuse regime is substantially similar to the E.U. regime). Thus, the sense used here is not only broader, it is also more colloquial and lay than the specialized legal term of art.

The special threat to market integrity arises because the intrinsic opacity of litigation finance assets enables efforts by would-be manipulators to sow seeds of doubt concerning the quality of company accounts. Usually, the sort of “tail risk” represented by Enron-style accounting fraud is remote from the imagination of most investors. However, the more opaque a publicly traded company’s asset portfolio, the easier it is to sow these doubts, making investor fears about tail risk more proximate.

A skeptic of the argument presented here might ask: “Sure, you call it ‘manipulation,’ which sounds mischievous, but where, exactly, is the problem here?” The skeptic might note that litigation finance companies assess the net pros and cons of public company status, including the possibility of a short attack or similar market-manipulative episode. If the company persists in listing, it knowingly assumes this possible downside risk, but impliedly has determined that the benefits outweigh said risks. Framed in this manner, that hardly presents a policy conundrum. However, the specter of market manipulation results in negative externalities from the perspective of the broader capital market.

Consider the following possible series of events. Becoming aware of the structural opacity of LFC fair value accounts, a speculator undertakes to sell the stock short, publicizing its inauthentic “belief” that the LFC’s fair value marks are overly optimistic. In such a circumstance, it can be rational for other investors to sell their shares, creating a positive feedback loop the net result of which is a decline in the price of the LFC firm.85A similar phenomenon could result from herd-like creditor behavior. See Xuewen Liu, Short-Selling Attacks and Creditor Runs, 61 Mgmt. Science 814, 822 (2015). This decline in price can also lead to a decline in intrinsic value, as the price declines operate to increase the firm’s cost of capital and affect its investment policies, in effect ratifying the initially pretextual description of the company’s accounts.86See Pingyang Yao & Pierre Jinghong Liang, Informational Feedback, Adverse Selection, and Optimal Disclosure Policy, 51 J. Acct . Res. 1133 (2013); see also Itay Goldstein & Alexander Guembel, Manipulation and the Allocational Role of Prices, 73 Rev. Econ. Stud. 133 (2008). For example, an investment promising an internal rate of return of 20% will be greenlighted by a firm with a weighted average cost of capital (WACC) of 18%, but will be declined by a firm with a WACC of 22% whether the WACC is established on an efficient market or is the result of market manipulation on the part of strategic short sellers.

The effects of market manipulation of this sort reverberate throughout capital markets. Tony D’Aloisio, the former chair of the Australian securities market regulator, lists the parade of horribles that might result from market manipulation of this sort:

Conceptually, the public cost of . . . market manipulation can be expected to be seen in the first instance in a widening in the bid–ask spreads for all trading in the securities in question. This can spill over into widening bid–ask spreads in the market for all securities, an increase in the cost of capital and a reduction in the market price of securities—not only for new and existing issues of the security in question but also for other securities. A reduction in market depth (reflecting reduced willingness to trade) and reduced trading volumes would also be expected. In a dynamic analysis, these higher costs of capital and costs of trading would feed into lower returns on investment, less fixed capital spending and less potential and actual economic demand and activity over the economic cycle.87Tony D’Aloisio, Chairman, Austl. Sec. & Inv. Comm’n, Insider Trading and Market Manipulation, Speech at Sup. Ct. of Victoria L. Conf. (Aug. 13, 2010), at 3–4, https://download.asic.gov.au/media/1347296/speech-insider-trading-market-manipulation-August-2010.pdf [https://perma.cc/8PLU-ZUYT].

Despite the evident costs for investors, the incentives persist for would-be manipulators. Unless enforcement is both forthcoming and effective, market manipulators do not themselves incur these economic costs.88See id. at 4.

These twin injuries to investor protection and market integrity would not pose an acute policy conundrum in the private fund context. In that setting, we might expect that informal norms, reputational considerations, and formal contracts would regulate and manage the uncertainty and opacity that saturates LFC accounts. But once these firms list their securities on public markets, they submit to a new regulatory regime, the objectives of which they can then potentially undermine.

Still, this argument that publicly traded LFCs present heightened risks to investors and market integrity hinges on an important premise: that LFC financial statements are inherently opaque and the product of a higher-than-normal degree of managerial discretion. While some further standardization might be expected in the medium- or long-term, particularly with the advance of predictive legal analytics,89See Robert F. Weber, Will the “Legal Singularity” Hollow out Law’s Normative Core?, 27 Mich. Tech. L. Rev. 97, 105–19 (2020). the reality is that today there exists no consensus on how to value litigation finance assets. The following Part will shed light on the significant degree of subjective discretion involved in most LFC asset valuation practices, as well as the potential for abuse that such discretion inevitably entails.

IV. LFC Assets and Fair Value Accounting

The securities disclosure complications for LFCs result primarily from the application of fair value accounting rules to litigation finance assets. This Part will guide the reader through the application of those fair value accounting rules. Accounting rules, along with scripture, are perhaps the only volumes of lexical rule systems that lawyers can push off to another profession. Even for a lawyer, tracing through labyrinthine

accounting rules can be vexatious. Nevertheless, all securities lawyers eventually learn that they cannot avoid engaging with the accounting rules from time to time.

Doing so here reveals a state of uncertainty regarding whether fair value rules do or do not apply to litigation finance assets, with the better argument probably lying in the affirmative position. Next, the Part

examines in detail how the publicly traded LFCs that adopt fair value accounting structure their fair value process and explain it to investors. It highlights in particular the unavoidable quantum of brute discretion that persists in that system, notwithstanding companies’ efforts to center the “objectivity” of their accounts.

A. How Fair Value Accounting Works Generally

One of the principal dilemmas in modern accounting is deciding whether to account for income and asset values by reference to cash flows and historical costs or by reference to current fair values.90See Ctr. for Excellence in Acct. & Sec. Analysis, Principles for the Application of Fair Value Accounting 2 (2008) [hereinafter Fair Value Principles] (“The issue of when, rather than how, to apply fair value measurements—as a matter of principle—is unresolved, even though fair value reporting has been required for selected financial assets and liabilities for some time.”). The former approach is thought to privilege clarity and certainty at the cost of some economic realism. The latter is thought to privilege economic realism at the cost of introducing discretion and the possibility of strategic manipulation and abuse. Two of the four publicly traded LFCs—Burford and Manolete—classify their litigation finance assets in a manner that requires fair value treatment.

Three of the publicly traded LFCs (Omni Bridgeway, LCM, and Manolete) are subject to the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) regime maintained by the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB).91See Manolete Partners PLC, Annual Report and Accounts 2022, at 27 (2022); Litigation Capital Management Ltd., 2021 Annual Report 36 (2021); Omni Bridgeway Ltd., 2021 Annual Report 55 (2021). The other (Burford Capital) reported in accordance with IFRS until 2022, when it voluntarily elected to present its 2021 financial statements in its annual report in accordance with the U.S.-based Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) accounting regime, maintained by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB).92In general, public companies listed on U.S. stock exchanges must comply with GAAP. See Raj Gnanarajah, Cong. Rsch. Serv., IF10701, Introduction to Financial Services: Accounting and Auditing Regulatory Structure, U.S. and International 1 (2021), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10701/7 [https://perma.cc/2U2V-LAMU]. However, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission also accepts IFRS preparation for so-called “foreign private issuers” (FPIs). See Form 20-F, Item 17(c). Burford, the only U.S.-listed LFC, historically prepared its financial statements consistent with IFRS. The ability of a U.S.-listed public company organized outside the United States to continue to do so depends on it maintaining its FPI status. See id. at gen. instr. A(a). Exchange Act Rule 3b-4(c) defines FPI to include all non-governmental foreign issuers that are not both (1) majority owned (in terms of voting securities) by U.S. residents and (2) linked significantly to the United States in one or more of the following ways:(a) a majority of executive officers or directors as U.S. residents;(b) a majority of assets located in the United States; or(c) a principal place of business administration located in the United States.

See 17 C.F.R. § 240.3b-4 (2021). Burford takes the position that it still is an FPI, but nevertheless elected voluntarily to transition to GAAP. See Burford Capital Ltd., 2021 Annual Report 5, 148 (Form 20-F) (2022) [hereinafter Burford 2021 Annual Report]. Given the predominance of IFRS reporting in the industry as presently constituted, this Article focuses on the applicable IFRS rules.

However, fair value accounting is one arena where IFRS and GAAP have substantially converged over the past decade.93See Press Release, Fin. Acct. Standards Bd., IASB and FASB Issue Common Fair Value Measurement and Disclosure Requirements (May 12, 2011), https://www.fasb.org/cs/ContentServer?cid=1176158544944&d=&pagename=FASB%2FFASBContent_C%2FNewsPage [https://perma.cc/W98Q-JMYE]. In fact, the IFRS fair value regime applicable to the current cohort of publicly traded LFCs is in most respects substantively identical to that of the GAAP regime, set forth in Topic 820 of the FASB’s Accounting Standards Codification system.94See Fin. Acct. Standards Bd., Fair Value Measurement (Topic 820): Amendments to Achieve Common Fair Value Measurement and Disclosure Requirements in U.S. GAAP and IFRS (2011), https://asc.fasb.org/imageRoot/00/7534500.pdf [https://perma.cc/6642-MJ79] [hereinafter GAAP Fair Value Rules: Topic 820]; Fin. Acct. Standards Bd., Fair Value Measurement (Topic 820): Disclosure Framework—Changes to the Disclosure Requirements for Fair Value Measurement (2018), https://asc.fasb.org/imageRoot/81/118196181.pdf. [https://perma.cc/2Y8C-JNCK]. So the U.S.-based reader, likely more accustomed to thinking about accounting in terms of the GAAP regime, is relieved of the burden of wondering how these issues play out in GAAP terms. For purposes of the specific issue with which this Article is concerned—fair value accounting for so-called Level 3 assets—no significant differences exist between GAAP and IFRS. Burford acknowledged as much when it reported its first GAAP-compliant results in early 2022.95See Burford 2021 Annual Report, supra note 92, at 26.

The accounting treatment of future contingent cash flows from litigation finance assets begins with “recognizing” the cash flows. This taxonomic project begins with IFRS 9, which governs the accounting treatment of financial instruments, including “financial assets.” IFRS 9 incorporates the definition of “financial asset” from IAS 32,96See Int’l Acct. Standards Bd., International Financial Reporting Standard 9 app. A (2020), https://www.ifrs.org/content/dam/ifrs/publications/pdf-standards/english/2022/issued/part-a/ifrs-9-financial-instruments.pdf?bypass=on [https://perma.cc/7CX5-T5RP] [hereinafter IFRS 9]. which includes, among other instruments, any “contractual right . . . to receive cash or another financial asset from another entity . . . .”97 Int’l Acct. Standards Bd., International Accounting Standard 32 ¶ 11(c)(i) (2020) [hereinafter IAS 32]. If an LFC “recognizes” its litigation finance assets as financial assets, IFRS 9 next makes the precise accounting treatment depend on how the LFC “classifies” the asset.98See IFRS 9, supra note 96 ¶ 3.1.1. Chapter 4 of IFRS 9 clarifies that the proper classification of a financial asset, in turn, is a function of the contractual cash flow characteristics of the financial asset.99See id. ¶ 4.1.1. Technically, the specific fair value accounting treatment is a joint function of both the cash flow characteristics and the business model pursuant to which the entity holds the financial asset. However, this latter criterion is only relevant where the relevant cash flows consist exclusively of interest and principal, and therefore do not come into play in the litigation finance context.

For litigation finance assets, the relevant provision of Chapter 4 is paragraph 4.1.4. The provision requires that financial assets be measured at fair value through profit and loss where the cash flows related to the asset do not consist exclusively of “payments of principal and interest [on specified dates] on the principal amount outstanding.”100See id. ¶¶ 4.1.4., 4.1.2. Both of the publicly traded LFCs classifying their assets as “financial assets” report fair value adjustments through profit and loss. See Manolete 2020 Annual Report, supra note 60, at 46; Burford 2020 Annual Report, supra note 34, at 61. Where, on the other hand, the financial asset gives rise to cash flow rights consisting exclusively of principal repayment and interest payments on specified dates, then the instrument should be either reported at amortized cost (if it is held within a business model whose objective is to hold financial assets) or at fair value through other comprehensive income (if it is held within a business model that contemplates the sale of financial assets). See IFRS 9, supra note 96, ¶¶ 4.1.2-4.1.2A. In accounting practice, this means that the assets are periodically revalued, with the incremental changes reflected as profit (in the case of an upward fair value adjustment) or loss (in the case of a downward fair value adjustment) on the income statement for the period in which the fair value adjustment occurs. This is significant and potentially confusing, for it means that the idiosyncratic, non-standardized features of litigation finance assets are responsible for fair value movements that directly impact the financial statement responsible for reflecting the operational realities of the business—that is, the income statement.