Civil Jury Trial Discussions in Colorado: Perspectives from Judges and Attorneys after Twenty-Five Years of Jury Reform

I. Introduction

The friends and adversaries of the plan of the convention, if they agree in nothing else, concur at least in the value they set upon the trial by jury; or if there is any difference between them it consists in this: the former regard it as a valuable safeguard to liberty; the latter represent it as the very palladium of free government.1The Federalist, 83 (Alexander Hamilton).

In my introductory remarks to the venire at every jury trial over which I preside, I tell prospective jurors that jury trials are a fundamental part of our judicial system and our system of government. I quote a paraphrased version of the epigraph above by Alexander Hamilton, emphasizing to the venire that he described the right to a jury trial “as a valuable safeguard to liberty” and “as the very palladium of free government.”2Id.

The point highlights the importance that a jury plays in the judicial system and its fundamental role in deciding civil and criminal cases.

In the United States, the overwhelming practice in civil jury trials (and certainly in criminal trials) is that jurors must wait to deliberate until they have heard all the evidence, the attorneys’ closing arguments, and received the instructions on the law from the court. Generally, jurors may not discuss the evidence they are hearing or seeing as the trial progresses, and the judge, at multiple points during the trial, typically instructs jurors not to do so, especially before any recess.

Colorado, among a handful of other jurisdictions, is an exception to that practice.3Other states also allow pre-deliberation discussions in civil trials, beginning with Arizona in 1995. See Jessica L. Bregant, Let’s Give them Something to Talk About: An Empirical Evaluation of Predeliberation Discussions, 2009 U. Ill. L. Rev. 1213, 1215 (2009) (“In 1995, Arizona became the first state to officially authorize such discussions when it adopted Arizona Rule of Civil Procedure 39(f).”). Indiana and North Dakota also allow such discussions. Id. at 1215 n. 19. But in Indiana, the practice is allowed in both civil and criminal trials. Ind. R. Ct. Jury R. 1 & 20(a)(8). In the District of Columbia, while the practice is not enshrined in a rule of procedure, it is left to the trial judge’s discretion whether to permit pre-deliberation discussions. David A. Anderson, Let Jurors Talk: Authorizing Pre-Deliberation Discussion of the Evidence During Trial, 174 Mil. L. Rev. 92, 109–10 (2002).

In civil jury trials in district court, the district judge may allow pre-deliberation discussions by the jury.4Colo. R. Civ. P. 47(a)(5).

The practice that began in 1998 through a pilot program authorized by the Colorado Supreme Court now seems like an afterthought.5Rebecca L. Kourlis and John Leopold, Colorado Jury Reform, 29 Colo. Law. 21, 22 (2000).

District judges routinely allow pre-deliberation discussion and instruct juries accordingly. I am among those judges.

But since the pilot program, little has been done to revisit how jury pre-deliberation discissions are working. Indeed, since 1998, no empirical research has been conducted to address how the practice plays out in district court trials, how often district judges allow pre-deliberation discussions, or how often a judge exercises her discretion to limit (or prohibit) such a practice and why. Similarly, while attorneys were polled in 1998, no new empirical research has been conducted on their views about pre-deliberation discussions.

This article seeks to ascertain those views, primarily through surveys of district court judges and attorneys who try cases in district courts throughout the state. The findings based on the survey responses suggest continued satisfaction with the practice of mid-trial discussions by juries.

Overall, judges and attorneys continue to support the practice of juror pre-deliberation discussions in civil trials. The judge surveys suggest that judges believe juror mid-trial discussions help jurors better recall the evidence. Anecdotal accounts from judges suggest that the mid-trial discussions allow jurors to process and understand the evidence as it is presented by the parties. That, in turn, allows for final deliberations to be more efficient. These responses align with research conducted in the wake of Arizona’s adoption of mid-trial discussions. On the rare occasions that judges did not allow mid-trial discussions, they did so because they believed that the discussions would favor the plaintiff, who presents the evidence first. Very recent research, however, suggests that it may be the defendant who could benefit from allowing such discussions.

The attorney survey, which did not have many respondents, mirrored the judge survey in many respects. For example, the attorney respondents believe that it is the plaintiff who would benefit from allowing such discussions. Nearly all respondents were unaware of the recent research suggesting the opposite benefit. A few attorneys did not seem familiar with the practice of mid-trial discussions in Colorado.

A novel issued that both judges and attorneys raised in the survey responses is the presence of an alternate juror during the jury’s pre-deliberation discussions and the effects that the alternate could have on the rest of the group during the trial. This concern has not been the subject of academic research to date. This article, however, discusses several options attorneys and judges may consider to address this potential issue.

In the end, the jury reform experiment in Colorado had stood the test of time. Given the robust research supporting jury reforms like mid-trial discussions, other jurisdictions should consider adopting them. The groundwork has been laid, the research shows that relevant parties favor them, and they make for more engaged and interested jurors.

This article begins by discussing the structure of Colorado’s trial courts and traces the history of juror pre-deliberation discussions in civil cases in the state. The next part is devoted to a discussion of the empirical findings on how pre-deliberation discussions affect juror satisfaction and comprehension of evidence. Finally, the article discusses the results of the new surveys and presents ideas for future research based on the results. The article concludes with recommendations for best practices for judges and attorneys to better understand and to maximize the utility of juror pre-deliberation discussions.

II. Judicial Organization and Pre-deliberation Discussions in Colorado.

Jurors in their earliest stages were allowed to freely consult with each other, investigate matters, and make findings accordingly.6Jack Pope, The Jury, 39 Tex. L. Rev. 426, 430–31 (1961).

But after several hundred years of evolution, juries became passive recipients of information presented by counsel at trial.7B. Michael Dann, ‘Learning Lessons’ and ‘Speaking Rights’: Creating Educated and Democratic Juries, 68 Ind. L.J. 1229, 1232 (1993).

In eighteenth-century England, William Blackstone described a civil jury that all would recognize today. William Blackstone, 3 Commentaries on the Laws of England 352–73. However, Blackstone explained that the jury, after hearing all the evidence in open court, deliberated in private, often without access to food or drink:

THE jury, after the proofs are summed up, unless the case be very clear, withdraw from the bar to consider of their verdict: and, in order to avoid intemperance and causeless delay, are to be kept without meat, drink, fire, or candle, unless by permission of the judge, till they are all unanimously agreed. A method of accelerating unanimity not wholly unknown in other constitutions of Europe, and in matters of greater concern.

Id. at 375.

These English rules, including prohibiting pre-deliberation discussions, were imported to America’s model of the jury trial.8Anderson, supra note 3, at 94–95.

The purpose was to ensure juror open-mindedness until the evidence concluded.9Id. at 95 (see for list of primary justifications for original prohibition against pre-deliberation discussion).

With jury reforms in the 1990s, beginning with Arizona and then Colorado, American jurisdictions sought to empower civil juries with some of their earlier qualities as more active participants in a trial.10Anderson, supra note 3, at 92, 104–05, 110.

A. The Juror Pre-Deliberation Discussions Pilot Program and Adoption of a Model Jury Instruction

In response to citizens’ growing dissatisfaction with their jury service,11Report on the Effective and Efficient Use of Juries 3, Colo. Sup. Ct. (Feb. 1997), https://www.courts.state.co.us/userfiles/File/Court_Probation/Supreme_Court/Committees/Jury_System_Standing_

Committee/juryref_1.pdf [https://perma.cc/4T28-34WY].

then- Colorado Supreme Court chief justice Anthony Vollack formed the Colorado Supreme Court Committee on the Effective and Efficient Use of Juries in Colorado (Jury Committee) in early 1996.12Id.

Citizens were dissatisfied, in part, because they felt “that the jury system cares little for the jurors themselves.”13Id.

Accordingly, the chief justice “directed the committee to study and recommend improvements to the jury system designed to enhance the effectiveness of communication with jurors as well as to assure the efficient and courteous treatment of jurors.”14Id.

The Jury Committee was comprised of twenty-seven members from a broad array of stakeholders, like jurors, jury commissioners,15A jury commissioner oversees the summoning of juries in a judicial district.

academics, civil and criminal attorneys, a newspaper editor, legislators, and trial and appellate judges. A little over one year after formation, the Jury Committee released twenty-six recommendations, 16Anderson, supra note 3, at 110.

including that “upon stipulation of counsel, courts should experiment in civil trials with permitting juror pre-deliberation discussions, particularly in lengthy or complex cases.”17Efficient Use of Juries Report, supra note 11, at 8.

The Efficient Use of Juries Report encapsulated the two main opposing views in favor and against pre-deliberation discussions. On the one hand, prohibiting jurors from discussing evidence before the presentation of all the evidence, seems impossible and against human nature.18Id. at 48–49.

Consequently, it would best to give jurors clear parameters on how to have such discussions mid-trial. On the other, detractors of the practice feared the “primacy effect” 19Valerie P. Hans et al., The Arizona Jury Reform Permitting Jury Trial Discussions: The Views of Trial Participants, Judges, and Jurors, 32 U. Mich. J.L. Reform 349, 366, 368 (1999).

—the idea that the plaintiff, in presenting their argument and evidence first, would gain an advantage by setting the tone for the following discussions.20The Efficient Use of Juries Report said:

Prohibiting jurors from talking about the case as the trial progresses may be contrary to basic human psychological needs and the adult learning process.

Some commentators have urged that, because pre-deliberation discussions will occur regardless of whether they are permitted, the interests of justice are better served by giving jurors guidance on when and how such discussions should take place.

The contrary view recognizes . . . fear[s] is that if the jury discusses the matter prior to hearing all of the evidence, the arguments of counsel, and the instructions on the law of the particular case, the jury could reach a decision and become intractable, or certain jurors could dominate the process.

Efficient Use of Juries Report, supra note 11, at 48–49.

Despite concerns about the primacy effect, the Colorado Supreme Court adopted the Efficient Use of Juries report in February 1997 and allowed the recommended pilot program on juror pre-deliberation discussions to proceed. 21Id. at 49.

The pilot study involved fifty-three jury trials in eleven different jurisdictions and it polled jurors, judges, and attorneys.22Kourlis & Leopold, supra note 5, at 22.

In 2000, after the pilot program concluded, jurors polled “overwhelmingly supported” pre-deliberation discussions, with ninety-three percent saying the practice was somewhat helpful or very helpful in “help[ing] them better understand the evidence and resolve confusion about the evidence during trial.”23Id.

“Ninety-four percent . . . believed that informal discussions improved formal deliberations.”24Id.

While fourteen percent thought that pre-deliberation discussions “encouraged jurors to make up their minds before all the evidence was presented,” a strong majority (sixty-two percent) “disagreed with this conclusion.”25Id.

Judges polled also strongly supported the practice. Sixty percent strongly supported pre-deliberation discussions, while thirty-three percent were neutral on the matter, and only seven percent were against the practice.26Id.

Sixty-seven percent of judge respondents strongly agreed that juror pre-deliberation discussions improved juror understanding of the evidence, while a small minority—ten percent—believed that juror pre-deliberation discussions encouraged jurors to make up their minds before all the evidence and law is presented.27Id. at 24.

As noted above, attorneys were the least enthusiastic about the reform. Nineteen percent of attorneys “strongly supported” the practice before trying a case in which pre-deliberation discussions were allowed, but their support increased to thirty-two percent “after the attorneys’ involvement in a pilot trial.”28Id. at 22.

Thirty-four percent of attorneys strongly agreed that juror pre-deliberation discussions improved juror understanding of the evidence.29Id. at 24.

On the other hand, thirty-seven percent of attorneys strongly agreed that juror pre-deliberation discussions encouraged jurors to make up their minds before all the evidence and law is presented.30Id.

As a result of that pilot study, in the year 2000, the Supreme Court approved a modification to the Colorado Jury Instructions by adding a proposed new model instruction.31Anderson, supra note 3, at 112.

That model instruction tells the jury, among other things, that they may engage in pre-deliberation discussions while they are all present in the jury room and that they must not make up their minds about the case until they have heard all the evidence, arguments of counsel, and received the instructions on the law:

1:4A JUROR’S CONDUCT DURING TRIAL—ADMONITIONS

Now that you have been sworn to try this case, I will instruct you as to your conduct during the course of this trial.

DISCUSSIONS OF THIS CASE AMONG YOURSELVES WHILE THE EVIDENCE IS BEING PRESENTED TO YOU MAY OCCUR ONLY IN THE JURY ROOM AND ONLY WHILE ALL JURORS ARE PRESENT.

FORMAL DELIBERATIONS WILL OCCUR after you have heard all of the evidence, the instructions of the court, the arguments of the attorneys, and have gone to the jury room and selected a (Foreman) (or) (Forewoman). Only then should you begin to deliberate this case AND BEGIN TO FORMULATE YOUR VERDICT.

The reason for the rule is that you should not commit yourself one way or the other before you have had an opportunity to hear all of the evidence, instructions, and discussion of the other jury members. DURING YOUR DISCUSSIONS OF THE CASE BEFORE YOU HAVE HEARD ALL THE EVIDENCE, THE ARGUMENT OF COUNSEL AND ALL THE JURY INSTRUCTIONS, YOU MUST KEEP IN MIND YOUR OATH AS A JUROR TO WITHHOLD JUDGMENT UNTIL YOU HAVE HAD THIS OPPORTUNITY.

Do not discuss this case with anyone, EXCEPT AS NOTED ABOVE, until the Court instructs you otherwise.32Efficient Use of Juries Report, supra note 11, at 72; see also Colo. Sup. Ct. Committee on Civil Jury Instr., Colo. Jury Instr. § 1:4A (2022).

While the above model jury instruction was included in the Colorado Jury Instructions, there was no formal requirement mandating its inclusion in any civil district court case. 33Rule 51.1 generally directs the court to use “such instructions as are contained in Colorado Jury Instruction (CJI) as are applicable to the evidence and the prevailing law.” But the committee note Rule 51.1 also cautions that the model instructions must “be used with discrimination, keeping in mind that they are not law in themselves and, in order to continually provide accurate assistance to juries, must be refined and modified in accord with changes in statutes and the body of appellate decisions.” The pattern instructions in the CJI certainly carry considerable weight and a trial court should consider them when instructing a jury. But, in the end, the CJIs are “intended as guidelines.” People v. Rester, 36 P.3d 98, 102 (Colo. App. 2001); Colo. R. Civ. P. 51.1(1).

Such a decision was made purely at the discretion of the of the district court or by agreement of the parties.

B. Codification of Juror Pre-deliberation Discussions into the Rules of Civil Procedure

In 2009, the Colorado Supreme Court’s Civil Rules Committee (Civil Rules Committee), which is tasked with recommending amendments to the Colorado Rules of Civil Procedure, proposed codifying the model juror pre-deliberation jury instruction into Rule 47(a)(5) of the Colorado Rules of Civil Procedure. The minutes of the June 2009 meeting of the Civil Rules Committee, when that body initially discussed the proposed amendment to the rule, note:

The reported purpose of the Rule change was to formalize approval of a practice already in widespread use and to increase juror comprehension of the evidence presented during civil trials. It was noted that there is a growing body of research demonstrating that the traditional notions of a passive fact-finder in a jury trial may contribute to problems juries face in comprehending the evidence and rendering reasoned verdicts. . . . The straw vote was 13 in favor of a Rule change, none opposed and one abstention.34Committee on Rules of Civ. Procedure, Colo. Sup. Ct., Minutes 3 (June 26, 2009) (on file with author).

On June 7, 2010, the Colorado Supreme Court approved the proposed amendment to Rule 47(a)(5):35Colo. R. Civ. P. 47(a)(5).

Once the jury is impaneled, the judge will again explain in more detail the general principles of law applicable to civil cases, the procedural guidelines regarding conduct by jurors during the trial, case specific legal principles and definitions of technical or special terms expected to be used during the presentation of the case. Jurors shall be told that they may not discuss the case with anyone until the trial is over with one exception: jurors may discuss the evidence among themselves in the jury room when all jurors are present. Jurors shall also be told that they must avoid discussing any potential outcome of the case and must avoid reaching any conclusion until they have heard all the evidence, final instructions by the court and closing arguments by counsel. The trial court shall have the discretion to prohibit or limit pre-deliberation discussions of the evidence in a particular trial based on a specific finding of good cause reflecting the particular circumstances of the case.36Id.

Since the rule’s codification in 2010, jury pre-deliberation discussions apply to all civil trials in district courts.37Colo. R. Civ. P. 1. Notably, the pre-deliberation discussion rule solely applies in civil district court trials. It does not apply in civil county court trials. Indeed, the rules of procedure applicable to county court civil jury trials lack a similar provision. Compare Colo. R. Civ. P. 47(a)(5) with Colo. R. Civ. P. 347(a)(5).

C. How Does Rule 47(a)(5) Work in Practice?

In general, the Court and counsel should broach the issue of juror pre-deliberation discussions at the final pretrial conference and include them in the Trial Management Order.38Colo. R. Civ. P. 16(f)(3)(VII) (“The parties shall also include any other matters which are appropriate under the circumstances of the case or directed by the court to be included in the proposed Trial Management Order.”).

Rule 47(a)(5) creates a presumption that pre-deliberation discussions will be allowed, but it gives the district court discretion to prohibit the practice “in a particular case based on a specific finding of good cause reflecting the particular circumstances of the case.”39Colo. R. Civ. P. 47(a)(5). In my order directing the parties to draft a proposed trial management order, I include a section that addresses juror pre-deliberation discussions and solicit counsels’ views on the matter—meaning, whether the jurors should be permitted to discuss the evidence during trial and, if not, to provide justification for prohibiting the practice for the case. As noted previously, if the practice is not allowed, the court must make specific findings of fact as to why. In my experience, attorneys have objected to the practice in one case—a two-week medical malpractice trial. I overruled their objections and allowed the jury to engage in pre-deliberation discussions. That trial is the inspiration for this research project.

That language should be an invitation for counsel to raise any objections to the practice for the court’s consideration. In turn, the court must give reasons for disallowing the practice given the circumstances of the case.

If the court allows the practice, it should instruct the jury on the same during the preliminary instructions before opening statements. Once the jury is chosen and sworn in, the district judge should read the instruction contained in Rule 47(a)(5), among others. With specific reference to pre-deliberation discussions, the district judge, for instance, should repeat the instruction at every recess to ensure that jurors keep an open mind and do not discuss the case without all jurors being present in the deliberation room. The judge should also explain in more detail, and without commenting on the evidence of the case, what topics about the evidence they may and may not discuss: they should not announce or discuss verdict preferences (e.g., “defendant is liable,” “plaintiff should lose,” “defendant must pay lots of money for this,”) but they may discuss the testimony they have heard to ensure they understand it and they may discuss whether a witness is or is not credible and why, while still keeping an open mind until they have heard all the evidence, received the instructions on the law from the court, and heard closing arguments of counsel.

III. Existing Empirical Studies on Juror Pre-deliberation Discussions

The three leading empirical studies addressing the effects of juror pre-deliberation offer overall positive results on jury pre-deliberation discussions. While attorneys, judges, and jurors were initially wary of the reform, all stakeholders were more satisfied after experiencing the process. The studies also demonstrate overall juror compliance with court instructions. Perhaps the most surprising finding is the suggestion of a “recency effect” in the jury’s decision-making. This section summarizes the key findings of the three leading empirical studies:40Empirical studies involving real or mock juries number in the thousands and have been a topic of academic interest since the 1950s, when the first study dealing with jury decisionmaking occurred with the Chicago Jury Project. Dennis J. Devine et al., Jury Decision Making, 7 Psychol. Pub. Pol’y & L. 622, 623 (2001) (collecting empirical studies on juror decisionmaking). In their article, Devine et al. “provide a comprehensive review of published empirical research on jury decision making.” Id. at 625. The focus of this article, of course, is solely with juror pre-deliberation discussions, which is a relatively recent innovation considering that juries have been employed since the 1300s. A fourth article, which also contains additional results of the Hannaford study, is not summarized. See Paula L. Hannaford et al., Permitting Jury Discussions During Trial: Impact of the Arizona Reform, 24 L. & Hum. Behav. 359 (2000).

[1] Hannaford study: a survey of jurors, judges, attorneys, and litigants launched soon after Arizona introduced pre-deliberation discussion;41Hans et al., supra note 19 at 365 (1999). The study involved 100 civil jury trials in four different Arizona jurisdictions, randomly assigned to pre-deliberation discussions and control groups. Id.

[2] Diamond study: a recording of jurors engaged in pre-deliberation discussions and deliberations soon after pre-deliberation discussion was introduced in Arizona;42Sheri Seidman Diamond et al., Juror Discussions During Civil Trials: Studying an Arizona Innovation, 45 Ariz. L. Rev. 1, 4–5 (2003). In this study, the researchers videotaped juror discussions and deliberations in fifty civil trials, of which thirty-seven were allowed to discuss the evidence during trial and thirteen were not. Id. at 16. Filming jurors as they discussed the evidence and deliberated was unprecedented. In re: Civil Jury Filming Project, Ariz. Sup. Ct. Admin. Ord. 98-10 (Feb. 5, 1998), https://www.azcourts.gov/portals/22/admorder/orders99/pdf98/9810.pdf [https://perma.cc/Q9RR-MX77].

and[3] Kerr study: a mock jury simulation to measure the effects of pre-deliberation discussion.43Norbert L. Kerr et al., Should Jurors Be Allowed To Discuss Trial Evidence Before Deliberation?: New Research Evidence, 42 L. & Hum. Behav. 413, 415 (2018). Kerr and his colleague conducted “a jury simulation experiment on the effects of [juror pre-deliberation discussions].” They noted, “[s]uch a highly controlled laboratory study, while having its own inherent weaknesses . . . ideally offers high experimental control and can thereby overcome some of the problems with which Hannaford et al. and Diamond et al. had to wrestle.”

A. Stakeholder Opinions and Satisfaction.

The Hannaford study concluded that judges “were the most enthusiastic group” about allowing juror pre-deliberation discussions.44Hans et al., supra note 19, at 367.

Approximately seventy-five percent of the respondent judicial officers (twenty-nine out of forty) supported the reform while fifteen percent (six out of forty) opposed it.45Id.

Like the findings from Colorado’s pilot, support from attorneys and litigants was less enthusiastic than judges’ support.46It should be noted that there were also fewer respondents in these groups and the researchers posited that “support or opposition to the reform could have affected attorneys’ and litigants’ willingness to respond.” Id. at 368.

Interestingly, attorney and litigant respondents’ main concerns or objections were about the primacy effect47Id.

—i.e., the “advantages” the plaintiffs supposedly enjoy with allowing such discussions because they present “the case first.”48Id.

Still, plaintiff and defense attorneys were nearly equally split in their opposition to the new rule.49Id. at 368–69.

Exposure to the new practice also correlated with support for it compared to the control group.50Id. at 369 (“Litigants whose cases were randomly assigned to permit juror discussions are more likely than litigants in the control group to support the reform.”).

Jurors showed the same correlation: those who were allowed to discuss the evidence during trial were “much more positive about the reform than jurors who report no discussions.”51Id.

And, approximately seventy percent of the 686 jurors who were allowed to engage in pre-deliberation discussions reported having “at least one discussion about the evidence during the trial.”52Id.

The finding suggests that if the practice is allowed, it is very likely that the jurors will engage in discussions during the trial, which is both the hope and the expectation.

B. Compliance with Instructions and Logistical Challenges.

The Diamond study discovered that jurors did not always follow the requirement to speak about the case while all the members were present in the deliberation room.53Diamond et al., supra note 42, at 28.

On average, there were 16.1 “periods” (i.e., ten-minute windows) during trial when not all jurors were present in the room and, in those instances, discussions occurred in 27.9% of the time.54Id.

The researchers found that such discussions tended to occur at the beginning of the day, when jurors arrived, and during the lunch recess.55Id.

The Hannaford study also reported “logistical problems.” For example, it was difficult “to get all jurors together at the same time.”56Hans et al., supra note 19, at 372.

And some jurors were incredulous–– “shocked,” “a little bit surprised,” and in disbelief—at the prospect of being able to engage in pre-deliberation discussions.57Id. at 372–73.

Other drawbacks were that jurors were unsure of the topics they could discuss or could not discuss58Id.

and several jurors who were concerned that engaging in pre-deliberation discussions might lead them to prejudge the case.59Id. at 374.

The respondents in this category were less likely to engage in such discussions and less likely to support the reform.60Id.

C. Primacy/Recency Effect.

Perhaps the most weighty argument against juror pre-deliberation discussions is that they foster a primacy effect: they encourage jurors to express a verdict preference prematurely.

The Diamond study attempted to measure whether jurors’ discussions expressed preferences for the plaintiff, how often, the types of opinions expressed, and how other jurors reacted to them.61Diamond et al., supra note 42, at 55.

Surprisingly, the data revealed that of the trials in their sample, forty-four percent of the jurors’ verdict statements regarding liability were in favor of the defense.62Id. at 49, 52, Table. 6.1. Verdict statements depended upon the type of case and whether they dealt with liability or damages. But, in general, the researchers categorized any statement expressing a preference that one party was liable or negligent (or not) as meeting the criteria. Similarly, on damages, a verdict statement had to express a preference for a damage amount or rule out a specific amount to award to the plaintiff. Id. at 49–50.

There were fewer verdict statements on damages, but fifteen percent of them were also favorable to the defense.63Id. at 52, Table 6.1.

Further, despite concerns that juror pre-deliberation discussions would have a primacy effect, “verdict statements were far more likely to appear after the defense had presented its first witness than before.”64Id. at 55.

In fourteen of the twenty-two cases in the sample (or seventy-nine percent), jurors made such statements.65Id.

Still, in the remaining eight cases, jurors made verdict-preference statements before the defense had presented its first witness.66Id.

Similarly, the Hannaford study found that the majority of jurors did not think that the discussions encouraged them to make up their minds before all the evidence and the law was presented—still, a minority of jurors, twenty-six percent, thought otherwise.67Hans et al., supra note 19, at 377, Table 3.

Keeping in mind that their data sample was “quite small,” the Diamond study found there was virtually no difference in verdicts between the cases in which discussions occurred and the cases in which they were not allowed to occur. In the discuss sample (twenty-eight cases), plaintiffs won sixty-four percent of the time, while in the no-discuss sample (twelve cases), plaintiffs won sixty-seven percent of the time.68Diamond et al., supra note 42, at 63, Table 7.2.

The mean awards were also close: $31,912 in the discuss cases, versus $38,174 in the no-discuss cases.69Id.

Indeed, as opposed to the primacy effect, Kerr found a “recency effect.” As Kerr explained, in juror pre-deliberation discussions “the evidence presented later in the trial (and after the jury’s [discussions]) had relatively greater impact on the jury’s verdict than the evidence presented early in the trial (and prior to [such discussions)].”70Kerr, supra note 43, at 422.

When jurors were allowed to discuss the evidence mid-trial:

the evidence presented in the second half of the trial had disproportionate impact on the postdeliberation jury verdicts—that is, those who heard a very weak defense case . . . were much more likely to find for the plaintiff than those who heard a very strong defense case.71Id. at 420.

In the trial where no pre-deliberation discussions were allowed, the verdict scores did not differ in a statistically significant way.72Id.

The study’s findings suggest that “the net effect of permitting [pre-deliberation discussions] will be to bias verdicts in favor of whichever side would profit more from the jury paying greater attention and giving greater weight to the evidence presented after [those discussions] than before [them].”73Id. at 423.

D. Understanding of the Evidence.

The Hannaford study found that eighty-one percent of juror respondents (n=479) agreed that their trial discussions improved their understanding of the evidence, and an equal percentage (seventy-seven percent) supported the reform.74Hans et al., supra note 19, at 377, Table 3.

The respondent jurors also agreed that all their colleagues’ “points of view were considered in the trial discussions, disagreeing that the trial discussions were dominated by one or two jurors.”75Hans et al., supra note 19, at 371.

The Diamond study undertook a detailed study-within-the-study of five particular trials to determine the substance of the jurors’ discussions. Based on their detailed analysis, they found that “when jurors seek information or have differences of view about facts at trial, the exchange that follows while the trial is in progress results in an accurate picture of the evidence.”76Diamond et al., supra note 42, at 47.

The Kerr simulations found that pre-deliberation discussions aided jurors in paying more attention to the evidence than in the cases where jurors were not allowed to discuss the evidence.77Kerr, supra note 43, at 421.

The finding came with a caveat: while “juror discussion did increase self-perception of attention,” it was limited “to that portion of the trial that followed such discussion.”78Id.

In the study, that was after the trial’s mid-point.79Id.

In a real setting, this finding suggests that jurors’ self-perception of attention would begin to accrue after they have their first break following opening statements and the first witness in the plaintiff’s case-in-chief. The Kerr study also concluded there were “no significant effects” regarding jurors’ ability to remember the evidence between those who discussed the evidence and those who did not.80Id. at 422.

Apparently, however, jurors had a slightly better recall of plaintiff’s witnesses than defendant’s witnesses.81Id.

Finally, Kerr’s findings on whether jurors who engaged in discussions were able to correct each other’s misunderstandings of the evidence had counter-intuitive results. The study found no significant effects on jurors’ perception of “the complexity of the overall evidence, as well as how well they understood that evidence.”82Id.

But there were significant effects on jurors’ purported understanding of the statistical evidence: jurors who were not allowed to discuss the evidence claimed to have a better understanding of the expert evidence than jurors who did, suggesting that “the midtrial discussion increased jurors’ confusion about the complex statistical evidence.”83Id.

IV. The Research Project

The three leading studies on the matter present fascinating conclusions that attorneys trying a civil case and a judge presiding over a jury should give serious consideration. It is unclear whether these findings have made their way into the practice of law. Pre-deliberation is now enshrined in civil trial practice in district court trials in Colorado and it seems like an afterthought. Attorneys rarely object and judges do not necessarily broach the subject at the final pretrial conference.

In order to understand how judges can best instruct jurors and attorneys can best plan for pre-deliberation, this study asks how attorneys and judges in Colorado think about and handle jury pre-deliberation discussions in civil trials twenty-five years post-reform. To do so, surveys were sent to district judges in active service and to attorneys who generally practice civil litigation in state court. The judge survey asked questions about their experience with civil jury trials and juror pre-deliberation discussions from the perspective of a presiding judicial office (e.g., how many civil jury trials they have presided over, how often they discuss the issue with the attorneys, how often a party objects to the practice and on what grounds, how has the judge ruled, etc.), and their views regarding the results of certain research on juror pre-deliberation discussions (e.g., do they agree that such discussions are useful to improve jurors’ understanding of evidence presented). The attorney survey asked similar questions about the same topics.84See Appendix A for detailed methodology. For judges, the survey asked the respondents to recall their general impression of what has occurred in the trials over which they have presided. Naturally, the nature of the questions will yield somewhat imprecise results because the survey did not ask about specific cases and requested that judges rely on their memory of the course of their tenure. Results, therefore, should be interpreted with caution.

A. Results of the Judges’ Survey and Interviews

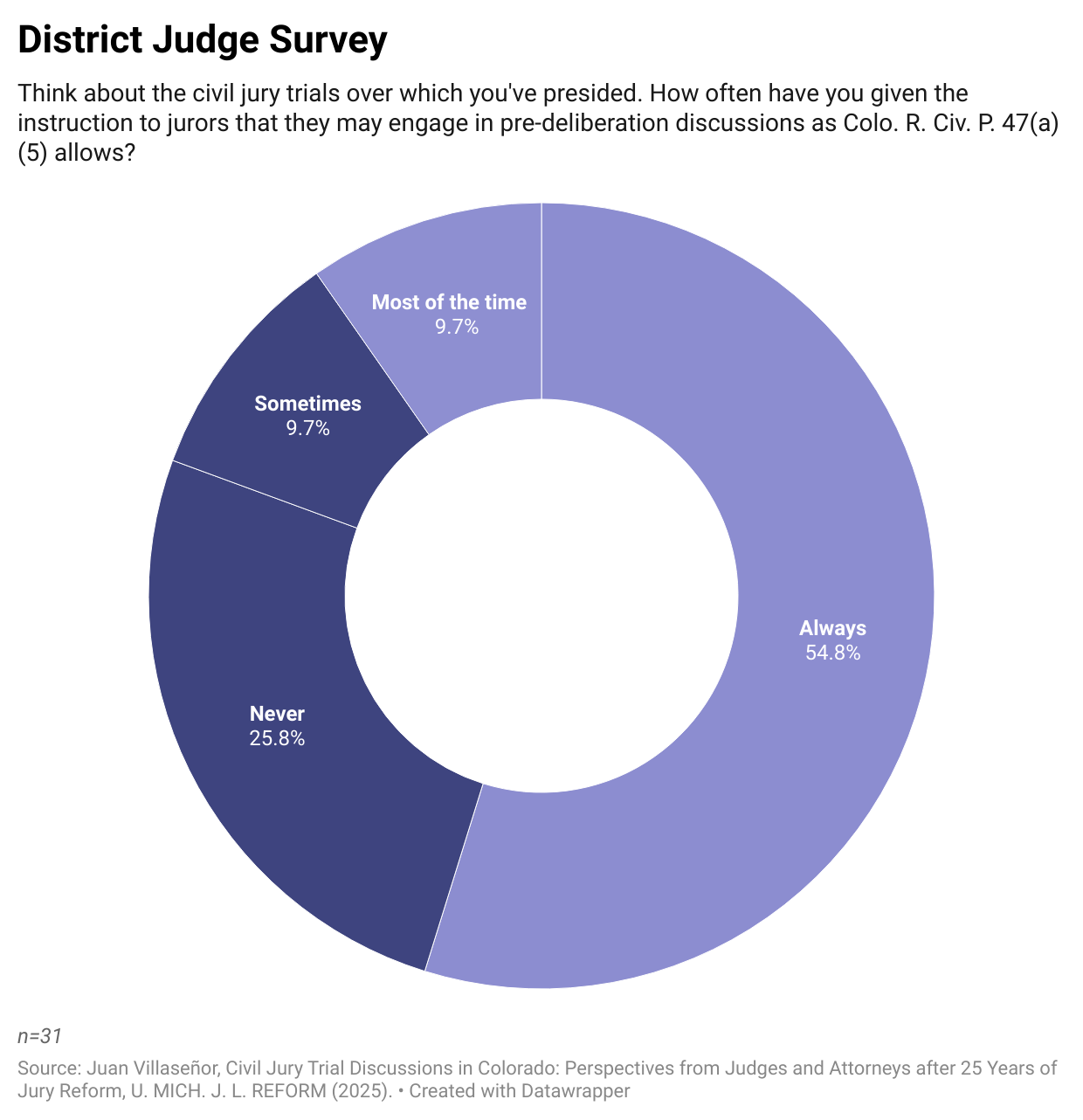

Survey. The results show that 20 respondents (n=31), or 64.5%, allow pre-deliberation “most of the time” or “always.” On the other hand, 11 (or 35.5%) “never” or “sometimes” allow the practice. In 83.9% (26) of the respondent judges’ experience, neither side—plaintiff or defendant—objects to allowing (or disallowing) pre-deliberation discussions, while 4 respondents said that both sides have objected, and 1 respondent said it was exclusively the plaintiff who objected.

Figure 1.

The survey attempted to ascertain the reasons why parties object to mid-trial discussions, asking the judge to provide the grounds for objections they have witnessed. 30 judges responded with a narrative answer. 22 responses indicated that the judge has not faced the issue (N/A), a party has never objected to the practice, or the judge did not remember what happened. Another judge stated that they were unaware of the practice because they “came from a criminal background” and no party had raised the issue. That answer suggests that pre-deliberation discussions were not allowed in that judge’s trials. The other responses indicated concerns about the primacy effect or concerns regarding an alternate juror engaging in pre-deliberation discussions and influencing the remaining jurors. Representative comments for not allowing the discussions were:

“The danger that jurors might make up their minds before hearing all the evidence.”

“The alternate juror could influence the thinking of the whole group prior to being excused from deliberation such that his or her influence impacts a verdict; Do not want the Defense to be at a disadvantage if discussion happens before Defense’s case is presented.”

Judges were asked their opinions regarding the statement “Attorneys trying a civil case in district court should consider juror pre-deliberation discussions as part of their overall trial strategy.”85Kerr found that pre-deliberation discussions suggested the existence of a recency effect when they were allowed. See Kerr, supra note 43, at 420. Such a finding suggests that trial attorneys—whether they represent a plaintiff or a defendant—should seriously consider and think about how pre-deliberation discussions may affect the verdict and should time the presentation of their evidence accordingly.

27 judges responded. Not surprisingly, several respondents (7 or 25.9%) neither agreed nor disagreed with the statement, likely reflecting the fact that judges are not advocates and their function is not to strategize like a lawyer trying a case. Still, 13, or 48.1%, “somewhat” or “strongly” agreed with the statement, which suggests that judges consider the practice an important component of a civil jury trial that is deserving of the attorneys’ attention and consideration.

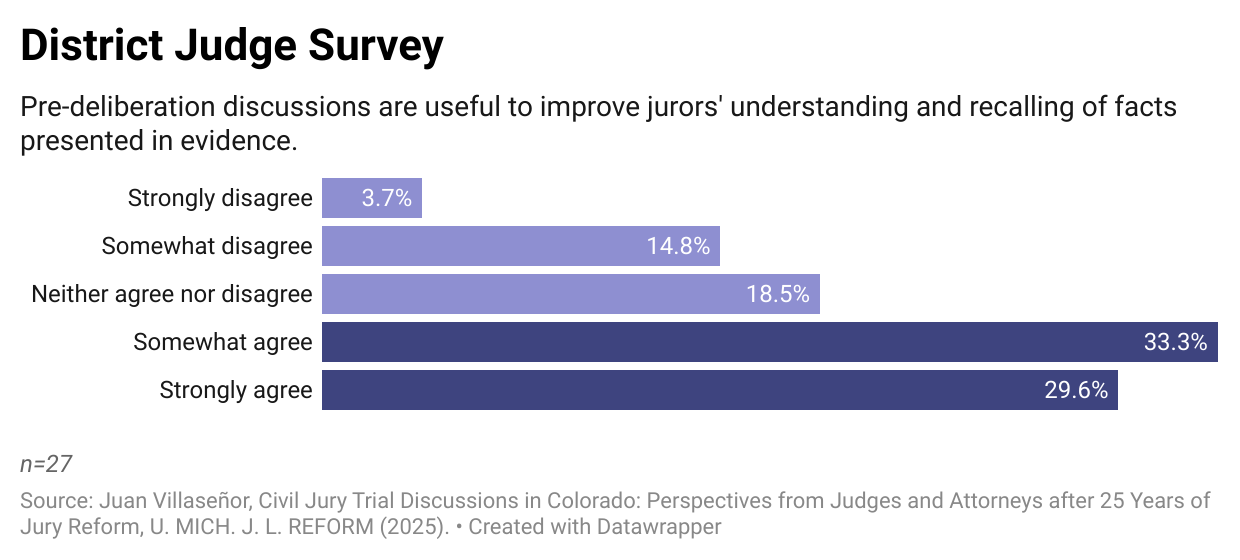

Judges were also asked their view on the following: “Pre-deliberation discussions are useful to improve jurors’ understanding and recalling of facts presented in evidence.”86See Kourlis & Leopold, supra note 5, at 22 (juror respondents found discussions “helped them better understand the evidence and resolve confusion about the evidence”); Hans et al., supra note 19, at 377 (eighty-one percent of juror respondents agreed that their trial discussions improved their understanding of the evidence); Diamond et al., supra note 40, at 47 (finding that in five particular trials, “when jurors seek information or have differences of view about facts at trial, the exchange that follows while the trial is in progress results in an accurate picture of the evidence”). But cf. Kerr, supra note 43, at 422 (finding no significant effects regarding jurors’ ability to remember the evidence between those who discussed the evidence and those who did not).

17 out of 27 respondents (62.9%) agreed with the statement, while 5 (18.5%) disagreed. 5 were agnostic on the issue. On the statement, “Pre-deliberation discussions allow the jury to reach a verdict more quickly than without them,”87The survey to jurors described in Kourlis & Leopold asked them whether pre-deliberation discussions made their “formal deliberations better or more effective.” Kourlis & Leopold, supra note 5, at 24. It did not ask whether the deliberation were shorter because jurors, presumably, had already discussed the evidence before beginning their formal deliberation. Based on my anecdotal experience and that of my colleagues, a belief exists that allowing such trial discussions allows the jury to reach a decision earlier than without them. The findings suggest that other judges also find it to be true. And while Diamond et al. found that the jurors who were allowed to discuss the evidence “completed their deliberations more swiftly than” the jurors who were not, “the differences were not statistically significant.” Diamond et al., supra note 42, at 75.

17 or 62.9% of respondents (n=27) “somewhat” or “strongly” agreed with the statement, while 5 (18.5%) “somewhat” or “strongly” disagreed, and 5 (18.5%) neither agreed nor disagreed.

Figure 2.

“Pre-deliberation discussions lessen the potential prejudice jurors experience from hearing inadmissible evidence because jurors would be able to discuss a judge’s limiting instruction.”88As noted in the Diamond study, one of the substantive topics of discussion during the jurors’ mid-trial conversations dealt with the instructions that the judge had given them during the trial. Diamond et al., supra note 42, at 35–37. Judges, and attorneys who request instructions from the court to a jury, hope that the jurors follow those instructions. It would beneficial if the jurors discussed such instructions during breaks to ensure that all the members of the panel understood them. And, the judge should repeat the admonitions discussed in supra Section II.C regarding the allowable parameters of mid-trial discussions by jurors.

15 respondents neither agreed nor disagreed with the statement. A slight number of respondents “somewhat” or “strongly” agreed with the statement (7 or 25.9%), while 5 (18.5%) had the opposite view.

Lastly, the survey asked respondent judges for their views on the statement, “Pre-deliberation discussions help jurors better understand expert witness testimony involving scientific, technical, or specialized knowledge.”89Diamond found that “jurors reported significantly greater ease in understanding the expert testimony when they had the opportunity to discuss the evidence during trial.” Diamond et al., supra note 42, at 71. Diamond also reported that jurors, in discussing the substance of the case during trial, discussed, among other things, the expert testimony they heard and whether that testimony conflicted with another expert’s. Id. at 36. These findings are contradicted by the Kerr study, which ironically found that mock jurors in his experiment may have been more confused about expert testimony because in the cases that did not allow mid-trial discussions, those jurors reported a better understanding of “complex statistical evidence.” Kerr, supra note 43, at 422. An important thing to keep in mind regarding this finding is that the results capture the mock jurors’ self-perceptions of their understanding of the evidence.

18 judges responded. As shown in Figure 3, 11 judges somewhat or strongly agreed with the statement (61.1%),90This result is similar to the result obtained by Kourlis & Leopold, who reported that sixty-seven percent of judges who responded to their survey strongly agreed that mid-trial discussions improved juror understanding of the evidence in general. Kourlis & Leopold, supra note 5, at 24.

while 3 (16.7%) held the opposite views. 4 did not have an opinion either way on the statement.

Figure 3.

Interviews. Two of the judges interviewed were from a jurisdiction along the Front Range, while one was from the Metropolitan Denver area.91See Appendix B for definitions of these geographical terms.

Front Range judge one is a relatively new judge, who had presided, at the time of the interview, over five civil jury trials. Front Range judge two has been a judge for approximately six years, but has presided over twenty to twenty-five civil jury trials, given his docket assignment. The Denver Metro judge has been a judge for twelve years and has presided over between seventy to one hundred civil jury trials. The Denver Metro judge stated that he “always” allows juries to engage in pre-deliberation discussion in his cases. Front Range judge one, however, has prohibited the practice in all but one of his five trials. While Front Range judge two has allowed the practice in every case, he questioned whether he should have permitted pre-deliberation discussions in one case. He believed that, based on his interview with the jurors after trial, the jurors formed verdict preferences before hearing all the evidence, contrary to his admonitions to the jury during trial. The judge elaborated that the case dealt with breach-of-contract claims. In retrospect, the judge noted, he would not have allowed the jurors to discuss the evidence during trial in that case and would have made the findings required under Rule 47(a)(5). By all appearances, it was a unique situation that did not change this judicial officer’s otherwise strong support for the practice.

One of the questions I asked during the interviews was whether the judges thought that pre-deliberation discussions were effective in helping jurors understand expert witness testimony involving scientific, technical, or specialized knowledge. The three judges answered enthusiastically in the affirmative. Front Range judge one believed that jurors ask better questions to witnesses because of their mid-trial discussions and that they “stay engaged,” which then allows them to better understand the evidence presented.92Colorado allows jurors to ask questions of witnesses, whether they are lay or expert. The rule applies in both civil and criminal jury trials. See Colo. R. Civ. P. 47(u) and Colo. R. Crim. P. 24(g).

Front Range judge two, who has only allowed the practice once, expressed similar sentiments in his response. The Denver Metro judge, who had recently concluded a civil jury trial, specifically brought up this issue to the jurors after the trial. The judge reported that jurors were very enthusiastic about their pre-deliberation discussions and that the discussions allowed them to better understand expert testimony.

Similarly, the three judges agreed that allowing pre-deliberation discussions made deliberations “more efficient.” Front Range judge two explained that, in his view, those discussions potentially allow the jurors to “wrestle” with factual disputes as the evidence is presented and by the time they begin their formal deliberations, they have sorted those out. That generally comports with my anecdotal experience speaking with jurors after trial, who express similar sentiments.

I was very curious about the Kerr study’s recency effect findings, which suggest that evidence presented later in a trial has “relatively greater impact on the jury’s verdict than evidence presented early in the trial.”93Kerr, supra note 43, at 422.

Naturally, this appears to be counter-intuitive because, one of the arguments against juror pre-deliberation discussions was based on concerns over a primacy effect. (Indeed, one of the narrative answers to the judges’ survey reproduced above indicates that very concern from counsel and it is why the judge prohibited mid-trial discussions.) The Denver Metro judge, in fact, expressed the view that pre-deliberation discussions would “harm” the defense because its case-in-chief comes after the plaintiff’s. Still, this judge remained steadfastly enthusiastic in his support for the practice.

All three judges were surprised at the Kerr study findings on this count. Front Range judge one, after learning about the Kerr study, became more willing to allow pre-deliberation discussions in civil trials, stating that he would be “willing to break a tie in favor” of allowing them, if there were an objection against them. Front Range judge two continued to support the practice, too, after learning of the Kerr study.

Summary. The thirty-four district judges who responded to the voluntary survey provide a good perspective of how Rule 47(a)(5) is used in Colorado district courts. While the intent of the rule was to create a presumption in favor of allowing pre-deliberation discussions in every civil jury trial in district court, 64.5% of the judges who responded allow them “always” or “most of the time.” A substantial minority (35.5%), however, “never” or “sometimes” allows the practice.

As with the Diamond study, the judges who do allow the practice are strong supporters of it. The narrative responses of the surveys indicate that the judges sustain an objection to the practice principally on the ground that such discussions suffer from a primacy effect—that the jurors will reach verdict preferences prematurely and in plaintiff’s favor.94See supra note 20 and accompanying text.

In my view, sustaining an objection to mid-trial discussions on those grounds does not provide good cause because it is a rare phenomenon that may be properly addressed with detailed instructions to the jury as to the purpose behind pre-deliberation discussions and what topics they may discuss versus what topics they may not.95See, e.g., supra note 39 and accompanying text.

The survey revealed that a majority of respondent judges believe juror mid-trial discussions help jurors better recall the evidence but few believed that such discussions would be helpful when the judge gives them a limiting instruction about inadmissible evidence they just heard. Extant research confirms, however, that jurors do discuss the judge’s instructions and admonitions to them.96Judges should, therefore, repeat the admonitions in Rule 47(a)(5) during every recess that jurors “may discuss the evidence among themselves in the jury room when all jurors are present,” and that they “must avoid discussing any potential outcome of the case and must avoid reaching any conclusion until they have heard all the evidence, final instructions by the court and closing arguments by counsel.” Colo. R. Civ. P. 47(a)(5). It would be advisable to further explain the rule to the jurors by making remarks like those set forth supra II.C.

Overall, the survey responses and the interviews indicated that juror pre-deliberation discussions are so woven into the fabric of a civil district court trial that they have become seamless. Still, the generation of judges under whom the practice came to be in the late 1990s and early 2000s have likely retired.97Under the Colorado Constitution, all judges must retire by the time the reach the age of 72. Colo. Const. art. VI § 23.

And with those retirements, the institutional knowledge surrounding the purpose of adopting juror pre-deliberation discussions and Rule 47(a)(5) likely went with them.

B. Results of the Attorneys’ Survey

The survey attempted to gauge how often counsel have discussed with their clients the issue of juror pre-deliberation discussions and whether counsel have objected to allowing them in civil trials. A minority (12%) of respondents (n=80) stated that they discuss the issue “half of the time,” “most of the time,” or “always.” Most respondents (87% percent), however, “never” or “sometimes” discuss the issue of jurors discussing the case during the trial with their clients. A substantial majority of the respondents, 60 out of 80 (75%), said they have “never” objected.98That could be the case for multiple reasons: the issue has never come up, the respondents support the practice and do not have reason to object, or the judge did (or did not) allow the practice and did not welcome objections to the same.

12 (15% percent) have objected to the practice “sometimes,” and 8 (10% percent) have objected “most of the time” or “always.”

Along the same lines, one of the questions asked respondents to state the grounds for objecting—if they have done so—to allowing jurors to engage in pre-deliberation discussions. The question requested a narrative response; 76 attorneys recorded responses, which varied and discussed multiple issues. 36 responses stated “not applicable,” with 1 of those explaining that “no one has ever requested juror pre-deliberation discussions.” 13 responses stated that the attorney has “never” objected to the practice, suggesting that they favor such discussions by jurors or are indifferent to the practice. 3 additional responses suggested that the attorney is unaware of the existence of Rule 47(a)(5) because they stated that the practice is not allowed in Colorado.99One of those responses stated that judges in Colorado instruct jurors not to discuss the case before they begin formal deliberations. While that is true in criminal trials, it is not the presumptive practice in civil jury trials in district court. It is possible, however, that the respondent’s experience could have been confined to county court, where the practice is not allowed. See supra note 37.

9 other responses expressed a concern about allowing pre-deliberation discussions over the primacy effect, noting the attorney’s concern that jurors may express verdict preferences during the plaintiff’s case-in-chief and influence other jurors during their mid-trial discussions. One of those responses stated: “I didn’t want the jury deciding the case when all they had was plaintiff’s evidence.”

10 responses indicated disfavor for the practice because of the presence of an alternate juror during the trial and allowing that juror to engage in such discussions: if such discussions are allowed, the alternate will participate in them but that juror may not be allowed to formally deliberate at the end of the case.100Rule 47(b) allows an alternate juror to participate in formal deliberations with consent of the parties and the court: “If the court and the parties agree, alternate jurors may deliberate and participate fully with the principal jurors in considering and returning a verdict.” Colo. R. Civ. P. 47(b). The rule, however, only applies in civil jury trials in district courts.

Indeed, one respondent allowed pre-deliberation discussions on the condition that opposing counsel agreed to allow the alternate juror to participate in formal deliberations. Otherwise, that attorney would not have allowed pre-deliberation discussions and prevented the alternate being involved in the decision-making process of that case.101The respondent phrased the response with the pronoun “we,” suggesting that the attorney either had co-counsel or consulted with the client about the matter, or both.

An attorney who had not objected substantiated the concern regarding the alternate juror, noting that in a “recent trial,” the alternate apparently dominated pre-deliberation discussions and contributed to the jurors making up their minds before the jury saw all the evidence, received the instructions on the law, and heard the attorneys’ closing argument.102Given the tenor of the response, it appears that the attorney was able to speak with the alternate juror or with the jurors after the case concluded and was able to glean that information from those conversations.

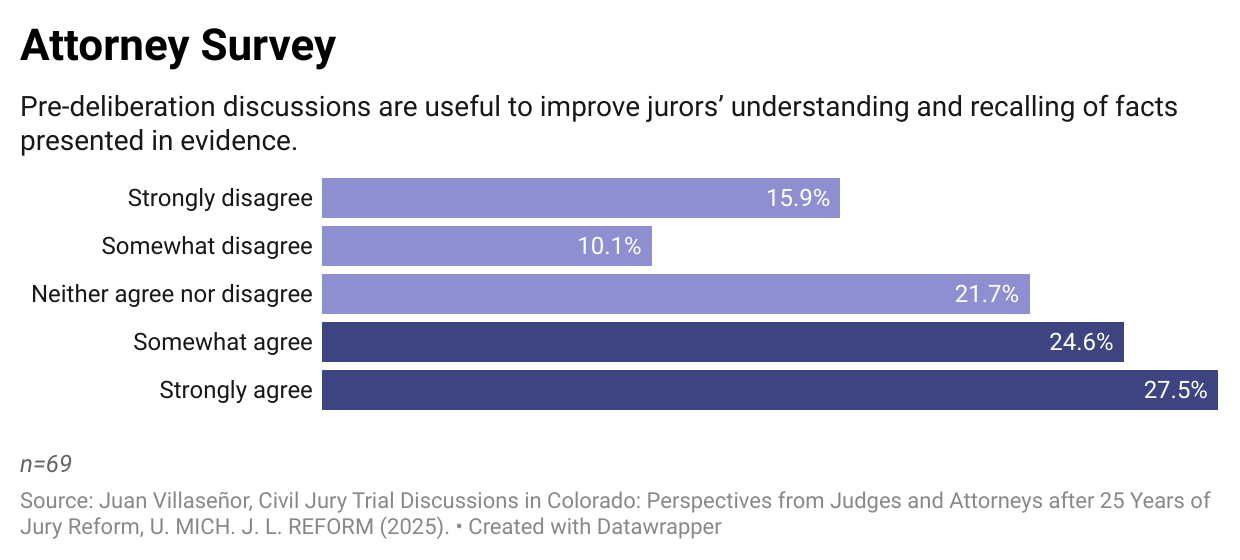

Figure 4 below shows attorney responses to the statement “Pre-deliberation discussions are useful to improve jurors’ understanding and recalling of facts presented in evidence.” 69 attorneys responded to the question. 36 (or 52.1%) somewhat or strongly agreed with the statement, while eighteen (or 26.1%) had the opposite views. 15 respondents (21.7% percent) neither agreed nor disagreed with the statement.

Figure 4.

The statement, “Pre-deliberation discussions allow the jury to reach a verdict more quickly than without them,” garnered similar responses as the previous statement. 38 out of 58 respondents (65.5%) somewhat or strongly agreed with the statement, while 12 had no preference one way or the other. A small minority, 13.9%, somewhat or strongly disagreed with the statement.

The statement, “Pre-deliberation discussions lessen the potential prejudice juror experience from hearing inadmissible evidence because jurors would be able to discuss a judge’s limiting instruction,” received similar responses to those of the judges’ survey. The majority of respondents neither agreed nor disagreed with the statement (28 out of n= 69 or 40.6%), while 23 (33.3%) were on the disagreeing side of the choices and 18 (26.1%) somewhat or strongly agreed with the statement.

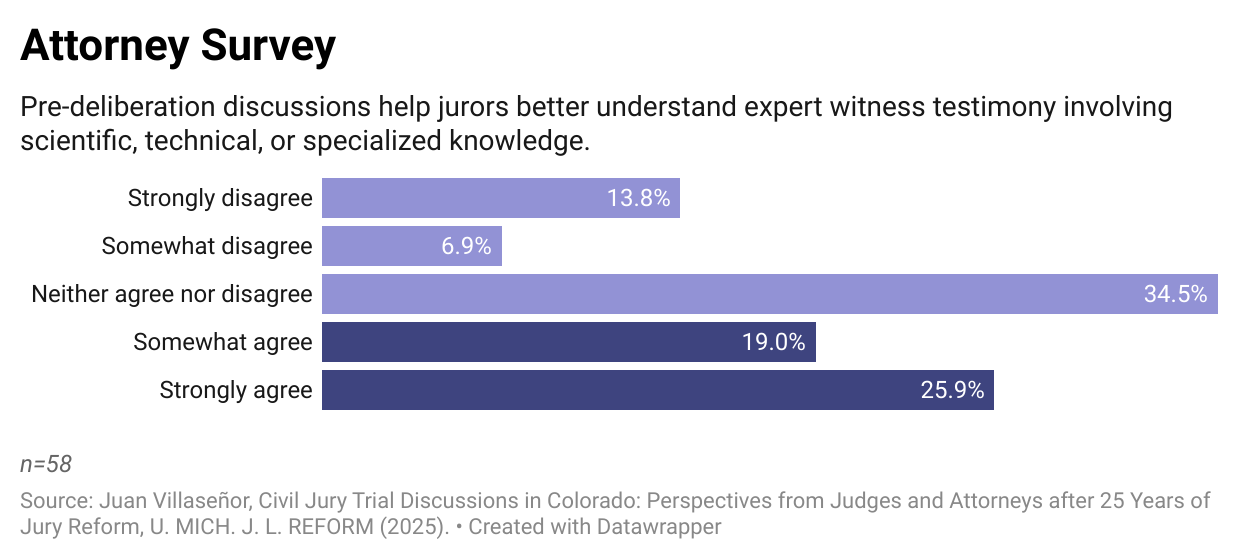

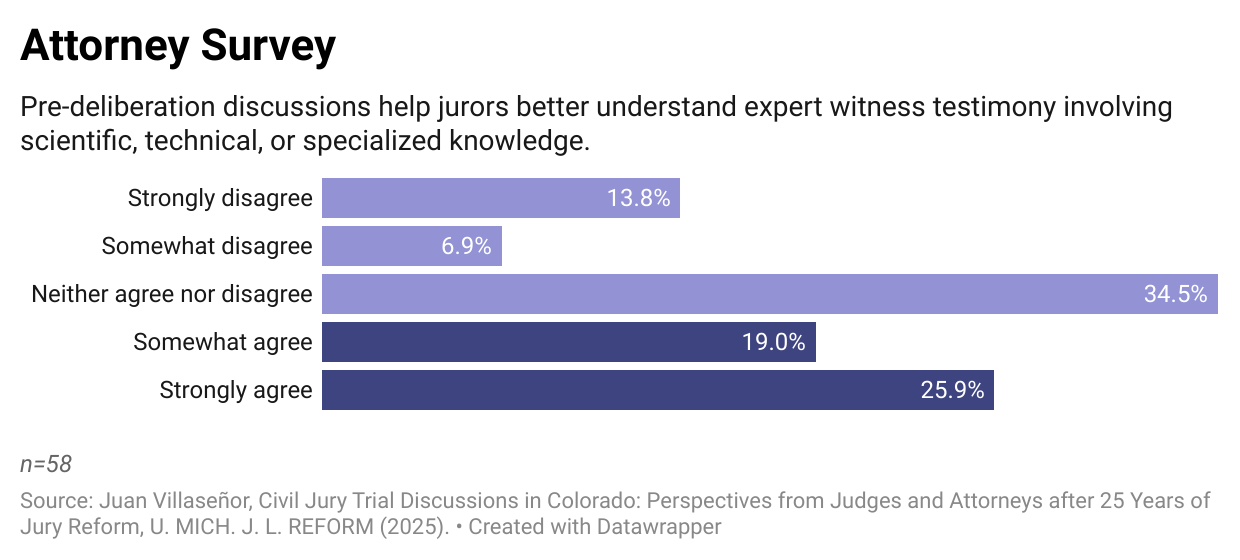

Lastly, the survey asked attorneys to express their opinion on the following statement: “Pre-deliberation discussions help jurors better understand expert witness testimony involving scientific, technical, or specialized knowledge.” Figure 5 below shows the results. 59 attorneys answered this question. 26 (44.8%) somewhat or strongly agreed with the statement, while 12 (20.7%) strongly or somewhat disagreed with the statement. A plurality (20 respondents, 34.5%) neither agreed nor disagreed with the statement.

Figure 5.

Summary. The 89 attorney responses, while representing mainly a plaintiff’s-side point of view, still provide a helpful perspective on how attorneys who practice in Colorado district court view juror pre-deliberation discussions.103The Duke University IRB approved this research project to conduct interviews of attorneys who responded to the survey. Duke Univ. IRB Protocol 2022-0513. Ultimately, I decided not to conduct interviews of attorneys due to ethical concerns. While the interviewees would be randomly selected and would remain anonymous per the protocol, I determined that through the interview they could receive (or interpret) information gleaned there that they could use to their advantage should they every appear in my court in a civil case. The opposing counsel, presumably, would not be privy to that information because I did not interview him or her. Thus, in the end, I elected not to conduct such interviews. Notwithstanding that fact, I believe that conducting interviews would have been helpful to the research project and would have aided in understanding the reasons behind attorneys’ practices and preferences regarding juror pre-deliberation discussions. Of course, none of the issues I just outlined applied to my interviews of district judges, who are my professional colleagues, holding the same office as I do.

It appears that concerns about the primacy effect, in which the plaintiff enjoys perceived “advantages” because he or she “presents the case first”104Hans et al., supra note 19, at 368. Further, the Diamond et al. found that, far from benefitting the plaintiff, primacy-effect related effects by jurors favored the defense in the trials that she studied. Diamond et al., supra note 42, at 49, 52. See also supra notes 61–65 and accompanying text.

continue to exist despite academic research contradicting that seemingly widely held belief. Surprisingly, no attorney considered whether a recency effect should be a concern and the majority of respondents do not broach the subject of pre-deliberation discussions with their clients at all. There are valid reasons for not doing so—it may be too much “inside baseball” for the client or the attorney may make a strategic decision on his or her own about that issue. It appears that because at least two attorneys are unaware of the existence of juror pre-deliberation discussions in district court trials, continuing legal education on this topic should be a priority for the bar.

A novel concern, which prior academic research has not identified, raised by several attorneys and some judges in their narrative responses, is the presence of an alternate juror during the jury’s pre-deliberation discussions and the effects that that juror may have on the rest of the group after they are dismissed and the jury begins formal deliberations.105See discussion supra Section IV.A, notes 100–102 and accompanying text. In general, an argument that pre-deliberation discussions should not be allowed because the parties chose to have an alternate juror is not very persuasive, absent additional grounds and good cause to prohibit the practice. Indeed, Rule 47(a)(5) does not carve out an exception to allowing mid-trial discussions because an alternate or alternates may be seated. Further, attorneys generally ask the court to sit alternate jurors, Colo. R. Civ. P. 47(b), and those jurors undergo the same selection process as do other jurors. See Johnson v. Schonlaw, 426 P.3d 345, 350 (Colo. 2018) (the alternate juror is “vetted and chosen in the same manner as the other jurors.”). Attorneys have the opportunity to question the alternate or alternates during voir dire and they know who will be seated in that role. Still, the research question of the effect, if any, that an alternate juror may have on the other members of the jury because of pre-deliberation discussions is worthy of further academic exploration. It cannot be understated how important it is to question the potential alternate juror to ensure that he or she will follow the court’s instructions on the law and will abide by the restrictions of pre-deliberation discussions. Additional issues to be explore could include, for example, the juror’s personality: Is he a leader or a follower? Will the alternate dominate discussions or be a team player? These are but two examples of areas that should be explored by counsel. If counsel have a general concern about an alternate engaging in mid-trial discussions with the other jurors, they may request to the court additional peremptory challenges, which would increase the number of the presumptive panel and may allow a party the ability to strike an alternate juror, with a view to seat a different alternate on the jury. Indeed, at least in Colorado, the district court has discretion to allow additional peremptory challenges. Colo. R. Civ. P. 47(h). (“Additional peremptory challenges in such number as the court may see fit may be allowed to parties appearing in the action either under Rule 14 or Rule 24 if the trial court in its discretion determines that the ends of justice so require.”).

This issue does not appear to have been addressed by Hans, Diamond, or Kerr in their respective studies. It is certainly a valid concern, and it is one that counsel should bring to the judge’s attention at the final pretrial conference. Moreover, this is an issue that should be studied either in a laboratory setting or in the context of actual trials as was done by Hans and Diamond.

V. Conclusion

Approximately twenty-five years have gone by since Colorado first introduced a pilot program to allow juries in civil district court trials to engage in pre-deliberation discussions. The practice, which was part of multiple jury reforms in Colorado in the late 1990s, was novel at the time. Colorado remains among a handful of jurisdictions that implemented substantive jury reform in the 1990s.

By and large, as the results of the surveys for this project show, the practice enjoys wide support. District judges and attorneys continue to support it. In many ways, the practice follows common sense, as Judge Schwarzer aptly noted in an article in the years leading up to the implementation of jury trial reforms by Arizona, Colorado, and other states:

In a complex and lengthy case . . . it defies reason to expect jurors, who may be confused, troubled, and perhaps overwhelmed by the unaccustomed responsibility, not to share their concerns and look to their colleagues for help and mutual support.106Hon. William W. Schwarzer, Reforming Jury Trials, 132 F.R.D. 575, 593–94 (1991).

It is surprising that pre-deliberation discussions remain a minority practice in American jurisdictions. With twenty-five plus years of positive experiences, more jurisdictions should seriously consider adopting the practice. They may do so through pilot projects, much like it happened in Arizona and Colorado. The benefits outweigh any potential risks.

Nevertheless, in Colorado (and likely other jurisdictions where the practice is allowed), more education is needed so that both judges and attorneys better understand the practice. Many still voice concerns about it—like the primacy effect—that are not borne out by academic research. But few are aware that recent research has found the opposite—the recency effect—and that it may affect verdicts. It is incumbent on the bench and bar to keep abreast of developments in this important area of the law to ensure that the practice is employed effectively and fairly.

It is essential that judges understand the research on this issue. A judicial officer’s principal job consists of ensuring that all parties have a fair trial. The judge, thus, must provide sufficient guidance to jurors to ensure that they follow the instructions on the law, including the instruction on how to engage in mid-trial discussions, to ensure that the jury keeps an open mind throughout the trial, and to wait on deliberating on final issues until they have received all the evidence, the arguments of counsel, and the court’s instructions on the law.

In general, the recent research regarding the recency effect highlights the importance of a rebuttal case at the end of the defendant’s case-in-chief and of a rebuttal closing argument by the plaintiff. The structure of a trial is set in stone: Plaintiff presents evidence first, since they generally have the burden of proof, defendant goes next after plaintiff rests, and then the plaintiff may present a rebuttal case. Opening statements and closing arguments by counsel proceed in the same fashion.

Considering the extant research, counsel must give serious thought to a rebuttal case and what part of the defense case to rebut. In general, rebuttal evidence should be significant to the claims at issue or to challenge any defenses. Counsel must avoid presenting rebuttal evidence that is trivial or immaterial. The same is true for a defendant’s case-in-chief. What evidence to present toward the end of their case-in-chief should be given significant thought and consideration. Presenting insignificant evidence at the end of any party’s case-in-chief should naturally be avoided because it could backfire. The same observations would apply to closing argument, and to a rebuttal closing argument by plaintiff. Choosing the arguments and evidence to highlight in a rebuttal is thus very important. Again, counsel should be judicious and not repetitive and clear as to what evidence and argument to highlight for the jury.

Appendix A. Survey & Interview Methodology

A(1): Survey Methodology

The Duke University Institutional Review Board (IRB) granted an exemption to this research project.107Duke Univ. IRB Protocol 2022-0513.

The participant population consisted of (a) attorneys licensed to practice law in Colorado who have a trial-level litigation practice in the state court system, and (b) Colorado district court judges who preside in courts of general jurisdiction. According to the Colorado Office of Attorney Regulation Counsel (OARC), as of April 5, 2022, there were 28,060 attorneys with active licenses.108Colo. Off. of Atty. Reg. Couns., 2021 Annual Report 1 (2022), https://coloradosupremecourt.com/PDF/AboutUs/Annual%20Reports/2021%20Annual%20Report.pdf, [https://perma.cc/7WHG-UYXK]. The OARC “works with the Advisory Committee and five other permanent Supreme Court committees in regulating the practice of law in Colorado. Attorney Regulation Counsel oversees attorney admissions, registration, mandatory continuing legal and judicial education, diversion and discipline, inventory matters, regulation of unauthorized practice of law, and administrative support for the Client Protection Fund.” Id. at 8.

The OARC does not track whether an attorney practices in any specific area of law.109See id. at Appendix C (providing data on type of law office attorneys work in but not the specific type of legal work performed).

It would be a reasonable estimate that a fraction of those 28,000 attorneys are litigators who have a civil trial practice in Colorado state courts. There are approximately 200 district court judges in active service in Colorado.110Colo. Jud. Branch, Office of the State Ct. Admin, Annual Statistical Report Fiscal Year 2021 17 (2023), https://www.coloradojudicial.gov/sites/default/files/2023-07/FY2021_Annual-Statistical-Report.pdf [https://perma.cc/XJ9Z-MC4R].

Participants were recruited in two principal ways. To recruit attorney participants, I requested assistance from the several specialty bar associations that have the largest number of attorney members who would likely practice in Colorado’s trial courts: the Colorado Trial Lawyers’ Association (CTLA), the Colorado Defense Lawyers’ Association (CDLA), the Colorado Women’s Bar Association (CWBA), and the Colorado Hispanic Bar Association (CHBA). The CTLA represents the interests of the civil plaintiff’s bar,111“Established in 1953, CTLA is the largest specialty bar association in the state. With over 1,300 members across Colorado, the association provides continuing legal education and training to trial attorneys in addition to networking opportunities, resources and professional development activities. CTLA also actively promotes individual rights through amicus briefs and the legislature.” CTLA, About CTLA, https://ts.ctlanet.org/?pg=AboutUs [https://perma.cc/7FPN-77JN] (last visited March 5, 2023).

while the CDLA represents the interests of the civil defense bar.112“CDLA is a statewide organization that is nearly 800 members strong, is dedicated to the defense of civil actions and the promotion of fairness and integrity in the civil justice system. The organization is comprised of attorneys who defend the interests of business and individuals in civil litigation.” CDLA, About CDLA, https://www.codla.org/about.php [https://perma.cc/W67S-ADWT] (last visited March 5, 2023).

The CWBA’s mission is “to promote women in the legal profession and the interests of women generally.”113CWBA, About Us, https://www.cwba.org/about-the-cwba [https://perma.cc/ZU4S-6M99] (last visited March 5, 2023].

The CHBA’s mission “is to serve Colorado and promote justice by advancing Hispanic interests and issues in the legal profession and seeking equal protection for the Hispanic Community before the law.”114CHBA, Mission & History, https://chba.net/mission-and-history [https://perma.cc/5E3N-KQ7U] (last visited March 5, 2023). For purposes of disclosure, I am a member of the CHBA.

I requested that those specialty bar associations send an email to their respective memberships requesting participation in the voluntary attorney survey. They graciously agreed. The email requesting the attorney’s participation was sent from the respective organization’s listserv to each attorney member. The body of the email contained a link to Qualtrics where the respondent could complete the survey. Those who accessed the survey via the Qualtrics link gave their informed consent to participate after reading a description of the research project and indicating the same by stating that they consented to begin the study.

Recruiting district judges was easier. As a district judge, I sent an email invitation to a listserv comprised of all active district judges in Colorado. The body of the email contained a link to Qualtrics where respondents could complete the survey. Those who accessed the survey via the Qualtrics link gave their informed consent to participate after reading a description of the research project and indicating the same by stating that they consented to begin the study.

Participants, whether attorneys or judges, were asked to complete their respective survey, which should have taken between ten and fifteen minutes. As part of the survey, participants were asked to provide some demographic information, such as the jurisdiction where they work, their years of experience, age, and gender. No participants were compensated for participating in the survey and participation in either survey was completely voluntary, with none of the questions (except the consent one) requiring a response.

Diamond’s observations about the weaknesses in the Hannaford study—that post-trial reports through a survey “are subject to failure of perception of memory”115Diamond et al., supra note 42, at 16.

—apply to the findings here too. None of the questions asked respondents about a specific case or cases, opting instead to have respondents rely on their memory and prior, general experience with trials. To anticipate for that potential inaccuracy, the surveys thus asked for estimated responses as described below.

A(2): Interview Methodology

Interviews were conducted with three district judges who responded to the survey. At the outset of the interview, I obtained their oral consent to conduct the interview. The interviews were not recorded and were conducted either over the phone or in person at the judge’s office. I took notes during the interviews to record the interviewees’ responses. My interview protocol, which was approved by the Duke University IRB, had thirteen questions.

Appendix B. Judge Survey Demographics

34 out of 196 (17.3%) district judges responded to the survey.116Not every respondent answered every question. While that is not ideal, the survey was voluntary and it did not require an answer to every question as noted in the body. The number of respondents will be noted as appropriate.

16 self-identified as men, 11 as women, 1 preferred not to identify with any gender identity, and the remaining did not answer the question at all. In terms of race or ethnicity, 16 said they were white or Caucasian, while 4 chose “other” or preferred not to say. 14 did not answer the question.

Judge participants were mostly between the ages of forty-five and sixty-four years old. 6 were sixty-five years old or older and 1 was the between the ages of thirty-five and forty-four.

The survey asked judges to generally identify the jurisdiction where they preside.117Colorado is a very large state: It is the eighth largest state in terms of surface area, with 104,094 square miles. U.S. Census Bureau, State Area Measurements and Internal Point Coordinates, https://www.census.gov/geographies/reference-files/2010/geo/state-area.html [https://perma.cc/6DLV-Z6Z7].

They had four choices: Front Range,118The Front Range is generally referred to as the area along Interstate 25, which runs south-to-north in Colorado, that encompasses Pueblo, Colorado Springs, Monument, Boulder, Greeley, and Fort Collins. It excludes any communities in the Denver metropolitan area.

Denver metropolitan area,119The area includes Denver County, Adams County, Jefferson County, Arapahoe County, and Douglas County.

Rural,120This area encompasses the counties on the Eastern Plains, east of Interstate 25, to the Kansas border.

and the Western Slope.121This area encompasses all mountain communities west of Interstate 25 and Grand Junction at the western end of the state.

The vast majority of respondent judges were from the Denver metropolitan area and from the Front Range (14 and 12, respectively). Two identified the Western Slope as their jurisdiction and one was from a Rural jurisdiction.

To glean the respondent judges’ level of experience, the survey asked how long they had been a district judge (n=28) and how many civil jury trials they had presided over (n=34). 15 district judges had between one and ten years of experience, while 12 had between eleven and twenty years, and 1 had twenty-one years of experience or more.

There respondents had a wide array of experience presiding over jury trials. 35% percent of the respondents had presided over 31 or more civil jury trials, and 27% had presided over 51 or more trials. Nearly two-thirds of the respondents had relatively less experience: together, they had presided anywhere between 1 and 30 trials.

Appendix C. Attorney Survey Demographics

89 attorneys responded to the survey.122As with the judges’ survey, not every respondent answered every question. Again, this survey was voluntary and, aside from the question requiring consent to participate in the survey, it did not require an answer to every question. Admittedly, it is a very low response rate, given that the two principal organizations that forwarded an invitation to their members—CTLA and CDLA—have, combined, over 2,100 members. The CHBA and CWBA also have a robust membership and are some of the largest specialty bar associations in Colorado. The results from this survey should, therefore, be interpreted with caution. See supra note 111 and 112.

The sample was lopsided toward attorneys who principally represent plaintiffs (55 out of 83, or 66.3%), versus 16 who represent defendants and 12 who represent both plaintiffs and defendants. The results should, therefore, be interpreted with caution and keeping that potential viewpoint in mind. A majority of the respondents identified as male (48 of n=70), while 22 identified as female. The age distribution among the respondents was diverse. There were 30 attorneys between the ages of forty-five to sixty-four and attorneys between the ages of twenty-five to forty-four totaled twenty-six. 13 attorneys were over the age of sixty-five.