Reforming the Medical Expense Income Tax Deduction to Better Reflect “Crip Time”

Diane Kemker, J.D., LL.M.1Adjunct Professor of Law, Pepperdine Caruso School of Law, Loyola Law School (Los Angeles). A.B., Harvard College; J.D., UCLA School of Law; LL.M. (taxation), University of San Francisco School of Law. I wish to thank organizers and participants of events where earlier versions of this paper have been presented: AALS Disabled Law Professors and Allies Section Program, AALS 2024; LATCRIT 2023 Biennial Conference, Cornell University; ClassCrits Conference, Loyola Law School, Los Angeles (February 9–10, 2024). All errors are, of course, my own.

Introduction

Extraordinary medical expenses—whether due to a one-time occurrence or a chronic condition—happen on their own time. These expenses, their causes, and their consequences (medical, personal, financial, or all of these) can rarely be neatly cabined into a single calendar year. Treatment requiring an expensive prescription medication or complex surgery not covered by insurance may address a condition that arose over years. That condition may have interfered with a taxpayer’s ability to work in prior years, the current year, and perhaps for years to come, even for the rest of the taxpayer’s earning life. The medical condition of a taxpayer’s family member can do the same. The disruptions caused by these events may be so radical as to transport the person, as it were, into “crip time,”2The term “crip,” though perhaps jarring to some, is used by radical disability theorists themselves, and I use it as they do, in a re-appropriative move analogous to that of Queer Theory. See, e.g., Robert McRuer, Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability (2006); Robert McRuer, Crip Times: Disability, Globalization, and Resistance (2018); Crip Temporalities (Ellen Samuels & Elizabeth Freeman eds., 2021); Alison Kafer, Feminist, Queer, Crip (2013); Ellen Samuels, Six Ways of Looking at Crip Time, 37 Disability Stud. Q. (2017); Tamar LeRoy, What Is Crip Time?, Accessibility.com (Nov. 30, 2021) [https://perma.cc/73QW-84Q3]; Josefine Wälivaara, Out of Time: Crip Time and Fantastic Resistance, 25 Sci. Fiction Res. Ass’n. Rev. 238 (Summer 2022). See also Elizabeth Freeman, Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories (2010). an experience of time radically different than the norm. Or it may not. But regardless, the Internal Revenue Code as it currently operates does not even fairly reflect the economic reality, and it deprives many taxpayers who have large medical expenses of the full tax value of those expenditures. It discriminates even more acutely against those who have such expenses over many years, and it discriminates irrationally, on the basis of those expenses’ timing.

We all live in normative time. Or rather, we all live under it—under a regime structured by it—seemingly inescapably. Philosophers dating back at least to Immanuel Kant have reflected on the nature of time, as a necessary condition of apperception, seeking to account for how and why all our human experiences necessarily take place in time. But it has taken the work of some radical disability theorists, practitioners of self-described “crip theory,” to identify the concept of normative time, by distinguishing it from what some of them call “crip time.” It is normative time that regulates our industrialized world, and our academic world. It puts us on daily, weekly, monthly schedules, creates class times with strictly regulated starting and ending times, same for semesters, academic years, time to degree, time to tenure. . . . The tax year, too, is a paradigmatic example of “normative time”—fixed, regular, intersubjective, arbitrary, frequently unfair, justified, perhaps, by convenience—but whose?

In fact, normative time, in some cases, not only defines disability, but creates it—when disability just is the inability to comply with normative time, being “slow,” failing to develop or complete tasks fast enough, or on the right schedule, or in the right order. It is normative time that excites both the longing and the resistance of disability theorist and professor Ellen Samuels when she writes, in Six Ways of Looking at Crip Time:

I want to be aligned, synchronous, part of the regular order of the world.

Like the leaves just now turning as the year spins toward its end, I want sometimes to be part of nature, to live within its time. But I don’t. My life has turned another way.

I live in crip time, now.3Ellen Samuels, Six Ways of Looking at Crip Time, 37 Disability Stud. Q. (2017) (n.p.).

When (and why) might departures from normative time be justified? The essence of this proposal is rejecting the so-called “ineluctab[ility] of the integrity of the taxable year”4Stephen A. Lind et al., Fundamentals of Federal Income Taxation 645 (20th ed. 2021) (internal footnotes omitted).—its normative dimension— in the service of greater substantive fairness and as a first effort to bring the provocative idea of “crip temporality” (also called “crip time”) into the tax Code. The first part of this proposal argues that this change can be justified on grounds of equity and economic reality before turning to justifications more deeply grounded in disability theory.

Although the Internal Revenue Code, at 26 U.S.C. § 213, permits a deduction for medical expenses that exceed 7.5% of a taxpayer’s adjusted gross income (AGI), it limits that deduction to the taxable year (meaning, for individual taxpayers, almost always the calendar year) in which the expenses were incurred. This fails to take proper account of the economic reality of such expenses, and it also ignores the lived reality of the taxpayer who has incurred them. The large current standard deduction means that most taxpayers, including disabled taxpayers, will not itemize, so that those medical expense deductions—and the reality that stands behind them—will disappear forever. When medical expense deductions disappear this way, they are being treated in effect no differently than the discretionary consumption expenses made non-deductible by 26 U.S.C. § 262. The current framework not only deprives taxpayers who incur these expenses of the full economic value of the deduction, it puts these individual human taxpayers on a worse footing than a business owner who incurs “net operating losses,” permitted under 26 U.S.C. § 172 to be carried forward and deducted, indefinitely. The Internal Revenue Code quite reasonably recognizes that business losses may be greater than gains in a particular year and permits the taxpayer to take greater tax advantage of those losses by applying them against future earnings.

Why not do this for medical expenses, too? This Article argues that the Code should do no less for the human taxpayers who incur large medical expenses (analogous to “losses”) in a given year than it does for business losses. This approach would allow taxpayers to take fuller tax advantage of expenditures that negatively impact their earning power over multiple years, regardless of whether they exceed 7.5% of AGI or the standard deduction in the year incurred.

This change can be justified, without recourse to any abstract philosophical theory, as a simple matter of horizontal equity. Conventional approaches to tax law and policy already invoke horizontal equity in seeking to align tax treatment with economic reality and treat similarly-situated taxpayers similarly. This is important and valuable, as far as it goes. But if we also bring critical disability theory (aka “crip theory”) to bear, we get something more: not only an additional justification for this change (and others like it), but a new angle of vision on the Code itself. Critical disability theory can challenge our assumptions about matters as disparate as “productivity,” autonomy, personhood, and citizenship; and can show how these assumptions may be shaped by ableism and unexamined beliefs about disability. A study of “crip time” can illuminate the role played by “normative time” in our expectations about a meaningful and valuable life. We can then bring these insights into our study and critique of the Internal Revenue Code, a large and complex body of federal law that nearly every American engages with almost every day, knowingly or not.

At first glance, the Internal Revenue Code’s tax year, and an analysis of how we might apply §172’s carryforward/carryback mechanism to extraordinary medical expenses under § 213, may seem like a strange place for a highly theoretical, even philosophical, intervention based on the nature of time. Kant and Foucault might not seem obviously relevant to an argument about income tax deductions. What I hope to show, however, is that the épistémè of normative time plays an absolutely essential, though largely invisible, role in the Internal Revenue Code, as it does in our understanding of disability more generally.

More than twenty years ago, historian Douglas Baynton remarked that “disability is everywhere in history once you begin looking for it.”5Douglas C. Baynton, Disability and the Justification of Inequality in American History, in The New Disability History: American Perspectives 51 (Paul K. Longmore & Lauri Umansky eds., 2001). The same goes for the law: disability is everywhere here, too. I was inspired to bring disability theory into tax analysis when I was introduced to “crip time,” specifically, simply because time looms so large in tax law. I do not identify as a member of the disability community, but I deeply respect and attempt to honor the principle of disability activism that demands “Nothing about us without us.” So, in what follows, I aim to amplify the voices of disabled scholars and disability theorists, especially those whose contributions, often with no explicit connection to tax law or even law more generally, have been so fruitful in my thinking.

I. The Tax Code Framework

A. The Deductibility of Medical Expenses (§ 213(a))

In essence, the calculation of personal income tax involves totaling gross income, taking appropriate deductions, and multiplying what remains by the appropriate tax rate. The deductibility of any particular expense depends entirely on what the Internal Revenue Code says. In the oft-quoted case New Colonial Ice Co., Inc. v. Helvering, “Whether and to what extent deductions shall be allowed depends upon legislative grace; and only as there is clear provision therefor can any particular deduction be allowed.”6New Colonial Ice Co., Inc. v. Helvering, 292 U.S. 435, 440 (1934). Less widely acknowledged is that Justice Willis Van Devanter was quoting, without citation, Judge Augustus Noble Hand (cousin of Judge Learned Hand), who wrote, “The question whether deductions from income may be claimed depends on legislative grace.” Merle-Smith v. C.I.R., 42 F.2d 837, 842 (2d Cir. 1930) (Hand, J., concurring).

While the tax Code permits deduction of all expenses incurred in the “ordinary and necessary” course of business,726 I.R.C. § 162(a). “no deduction shall be allowed for personal, living, or family expenses.”826 I.R.C. § 262(a). Regardless of one’s standard of living, two taxpayers with the same adjusted gross income will owe the same tax, even if one of them has consumed their income in profligacy and high living while the other pinched pennies. Until 1942, medical expenses, incurred by the taxpayer on their own behalf or for their dependents, were treated as nondeductible “personal, living, or family expenses.”9Stringham v. C.I.R., 12 T.C. 580, 583 (U.S.T.C. 1949) (“Section 23(x) [now Section 213] was originally introduced into the Internal Revenue Code as section 127(a) of the Revenue Act of 1942. Prior to that time Congress had never seen fit to extend the benefits of such a deduction and had long regarded such expenditures as ‘personal, living, or family expenses,’ which were expressly not deductible by virtue of section 24(a) [now Section 262(a)].”). During World War II, Congress enacted § 23(x) (now § 213), which permitted the deduction of “medical expenses above a certain normal level,” with a dollar cap.10William Vickrey, Insurance Under the Federal Income Tax, 52 Yale L. J. 554, 556 n.10 (1943) (“Pub. L. No. 753, 77th Cong., 2d Sess. (Oct. 21, 1942) (hereafter cited as Pub. L. No. 753) inserts subsection 23(x) in the Internal Revenue Code to provide for the deduction of the excess of medical expenses over 5 per cent of net income, with a limit on the amount of the deduction of ,500 for a joint or head of family return and ,250 for other returns.”).

The Stringham case, decided in 1949, is one of the first in which the Tax Court clarified the line between deductible medical expenses and non-deductible family or personal expenses.11The very first case to require that analysis was Wendell v. C.I.R., 12 T.C. 161 (1949), decided several months before Stringham, disallowing the deduction of the salary paid to a practical nurse hired by George Wendell, Sr., to care for George Wendell, Jr., after George’s wife (the baby’s mother) died in childbirth. Prior cases interpreting or applying § 23(x) raised different issues. Genevieve Stringham was born in Shaker Heights, Ohio, in 1939, the middle child of Keever Stringham and his (unnamed) wife.12Stringham, 12 T.C. at 580. Genevieve was a sickly baby who became a sickly child. Hospitalized in her first year of life for ten days with pneumonia, she went on to have frequent colds, adenoiditis, chronic bronchitis and sinusitis, asthma, anemia, and at least once, a positive tuberculin test.13Id. In November of 1944, after another bout of “deep bronchitis bordering on pneumonia,”14Id. the family made what must have been a very difficult decision: to enroll their five-year-old child in a boarding school in Arizona, whose climate was recommended by her doctor.15Id. Her mother traveled there with her by train, remained in Tucson for a month, and returned to Ohio. As the Tax Court phlegmatically reports, “No member of the family thereafter visited Genevieve during the remainder of that school year,”16Id. at 582. some six months. Genevieve came home to Ohio on May 30, 1945, but returned to the Arizona Sunshine School for the 1945–1946 academic year.17Id.

At a time when the median U.S. household income was about $2,400,18U.S. Dep’t of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Income of Nonfarm Families and Individuals: 1946, Current Population Reports, Consumer Income, Series P-60, No. 1 Rev., at 8 (Jan. 28, 1948) [https://perma.cc/QUX5-RQ6A]. Keever Stringham, a thirty-one-year-old electrical engineer who had been working since the age of sixteen, claimed a medical expense deduction of nearly $2,000 on his 1944 tax return.19Stringham, 12 T.C. at 582. Tuition, room and board accounted for $1,381 of this amount. He also claimed some of the child’s travel expenses. (His wife filed separately, although she was not employed outside the home.)20Id. at 586. The Service disallowed it, but ultimately, the Tax Court permitted him to deduct that part of the expenditure that was not tuition (educational expenses are not deductible), and that exceeded the then-statutory floor of 5% of his adjusted gross income, and up to the statutory maximum of $1,250—a total of about $1,000.21Id. (“These amounts, in addition to the other medical expenses allowed by respondent, are deductible by petitioner in so far as the total amount exceeds 5 per cent of his adjusted gross income and, as it appears that his wife filed a separate return in 1944, to the extent of the statutory limitation of ,250.”).

Stringham helpfully introduces us to a family experiencing the extreme financial, medical, and psychological hardship of a sick child who does not get better for nearly a year, and who made the heart-wrenching decision to take their kindergartener to a place two thousand miles away (before air travel), and leave her there with strangers, to spend Christmas and many following months alone as the youngest child at the school.22Id. at 581. By the time the case was decided, we can only hope that Genevieve was a healthy ten-year-old, once again living with her family. The opinion never says. It does mention, however, that its holding about the deductibility of those 1944 expenses “is in no way determinative of [her father’s] right to claim similar deductions in subsequent years.”23Id. (It is unknown whether he did so.) The Stringhams’ tax and financial situation, it seems, remained as precarious as Genevieve’s health.

Since 1949, the precise percentages deemed nondeductible have risen and fallen, and the cap has also been raised, lowered, and ultimately eliminated. Today, the “floor” is 7.5%, and there is no cap.2426 I.R.C. § 213(a). Section 213(a) now provides:

(a) Allowance of deduction

There shall be allowed as a deduction the expenses paid during the taxable year, not compensated for by insurance or otherwise, for medical care of the taxpayer, his spouse [yes, it still says ‘his’!], or a dependent . . . to the extent that such expenses exceed 7.5 percent of adjusted gross income.25Id.

Three key features of § 213 are worth highlighting: deductibility extends to expenditures on behalf of other family members besides the taxpayer; only expenses exceeding 7.5% of a taxpayer’s AGI are deductible at all; and these expenses may only be deducted in the year in which they are paid.

A deductibility “floor” for medical expenses (which has been as low as 3%26Internal Revenue Code of 1954, Pub. L. No. 83-591, 68A Stat. 3 (1954). and as high as 10% of AGI27Affordable Care Act, Pub. L. No. 111-148, § 9013, 124 Stat. 119 (2010) [https://perma.cc/2FF8-RARF].) means that Congress views spending up to 7.5% of a taxpayer’s AGI on medical expenses as “normal,” or at least, not extraordinary. Expenditures up to that point are treated no differently than discretionary consumption expenses, or what we might call “lifestyle choices.” We can recognize even at this early stage of analysis that for many taxpayers, spending thousands of dollars a year on medical care, including prescription drugs, is nothing like a discretionary lifestyle choice. Whether the expense is for lifesaving or life-sustaining treatment; needed to enhance the taxpayer’s quality of life (or that of a family member); essential to ameliorate pain or suffering; or— as is often the case—necessary for the taxpayer to continue to work and support themselves and their families, it is nothing like purchasing a designer handbag, leasing a fancier car, or buying champagne in a nightclub. Not only is the expense generally non-discretionary in its nature, so too, typically, is its timing. The expense is incurred when it is needed, not wanted. This issue of timing will become a crucial part of the analysis.

B. The Effect of the Standard Deduction (§ 63(c))

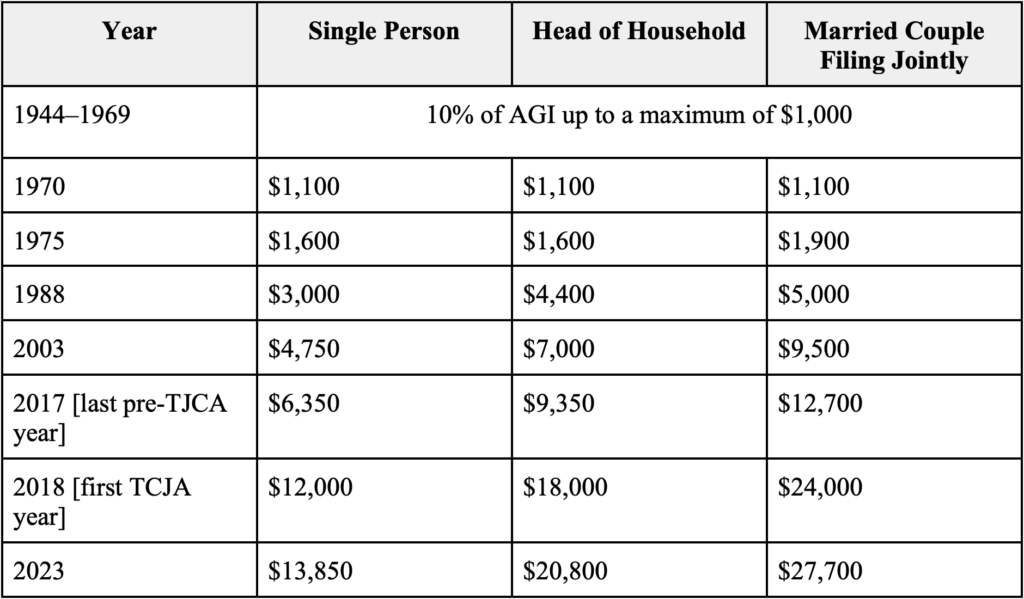

For the first decades of the income tax, there was no “standard” deduction; taxpayers were required to itemize to deduct any eligible expenses.28Internal Revenue Service, Personal Exemptions and Individual Income Tax Rates, 1913-2002, 217 [https://perma.cc/AA4J-BDAY]. The table below illustrates how the standard deduction has increased since its introduction in 1944, jumping significantly in 2018 in response to the Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA). As the standard deduction has increased, more taxpayers are likely to take the standard deduction rather than keeping careful records in the hope of deducting their aggregate medical expenses.

Table 1. A Brief History of the Standard Deduction29Id.; Internal Revenue Service, SOI Tax Stats – Historical Table 23, https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-historical-table-23 [https://perma.cc/4YD6-GQZF] (last updated Aug. 26, 2024); 26 I.R.C. § 63; Internal Revenue Service, Publication 505 (2024), Tax Withholding and Estimated Tax, https://www.irs.gov/publications/p505#:~:text=For%202023%2C%20the%20standard%20deduction,Head%20of%20Household%E2%80%94%2420%2C800 [https://perma.cc/MC5D-72DX].

Given the current size of the standard deduction and the complexity of itemizing deductions (keeping records and receipts all year long), it is perhaps unsurprising that the standard deduction is very “popular”: more than 90% of the more than 150 million personal tax returns filed in 2020, the most recent year for which the IRS has published data, took the standard deduction.30Tax Policy Center, How Did the TCJA Change the Standard Deduction and Itemized Deductions?, The Tax Policy Briefing Book, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/what-standard-deduction#:~:text=As%20under%20prior%20law%2C%20the,about%2070%20percent%20in%202017 [https://perma.cc/P2H4-PMLB]. (Prior to the TCJA increase, that figure was just below 70%.31Id. ) Although the standard deduction is subject to change when the TCJA “sunsets” at the end of 2025,32Id. because it is perceived as a “tax break,” it seems unlikely that it will go down.

C. Putting It Together

In order for it to make tax sense to itemize, a taxpayer must have deductible medical (or other) expenses greater than the standard deduction (see Table 1, supra). For all but the highest-earning taxpayers, the standard deduction will far exceed § 213’s 7.5% “floor” on medical expense deductions. A single taxpayer would have to have an AGI of almost $185,000, and a married filer would need an AGI of almost $370,000—enough to put that couple in the top 5% of earners in any state (and almost enough to be in the top 1% in West Virginia or Mississippi)33See Mike Winters, Here’s How Much Money You Need to Earn to Be in the Top 1% in Every U.S. State, CNBC Make It (Jan. 24, 2023) [https://perma.cc/8227-FJCE]. —for 7.5% to exceed the standard deduction, and make it rational for all statutorily-eligible medical expenses actually to be deducted.

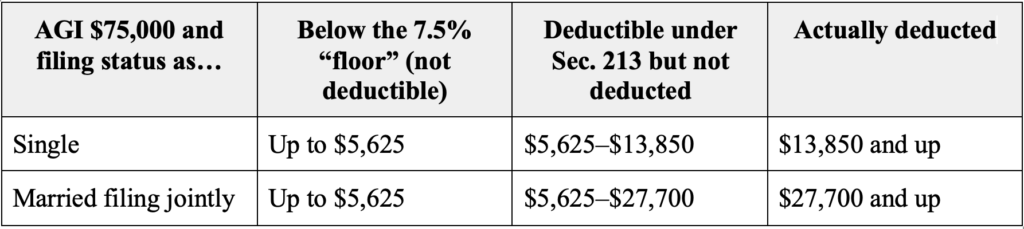

To come at it from the other side, for a taxpayer with a median AGI of $75,000,34Gloria Guzman and Melissa Kollar, Income in the United States: 2022 (2023), https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2023/demo/p60-279.html#:~:text=Real%20median%20household%20income%20was,and%20Table%20A%2D1) [https://perma.cc/XR23-TJPE]. medical expenses in excess of $5,625, 7.5% of AGI, would be deductible under the statute. But it will not make economic sense for a taxpayer with medical (and other deductible) expenses between $5,625 and almost $14,000 to forego the standard deduction and itemize (and take the medical deduction), because the taxpayer would get a larger reduction in their tax bill (and save a lot of time in record-keeping) by taking the standard deduction.35This reflects a simplifying assumption that the taxpayer does not have other deductions sufficient to warrant itemizing.

For a married taxpayer filing jointly, the discrepancy is even larger. Although married couples with $75,000 AGI are statutorily-eligible to deduct medical expenses exceeding $5,625, to exceed the standard deduction, that couple or family would need to have more than $27,700 in medical expenses, about 37% of their income.

In fact, because of transaction costs, including both record-keeping and a taxpayer’s assessment of the likelihood of being audited after itemizing or having medical deductions disallowed, a taxpayer would probably need to have deductions in even greater excess of the standard deduction before it would make sense to claim them.

Table 2. Effect of Standard Deduction on § 213 Deduction

Uninsured medical expenses incurred for oneself or one’s dependents are among the most significant expenses a taxpayer may incur in their life. In fact, nearly two-thirds of all bankruptcies in the United States are the result of medical debt.36Terri Turner, 49+ US Medical Bankruptcy Statistics for 2023, RetireGuide (Oct. 20, 2023), https://www.retireguide.com/retirement-planning/risks/medical-bankruptcy-statistics/ [https://perma.cc/8N26-B6VY]. Medical care is itself expensive, and frequently has a negative impact on earnings. Whether the taxpayer themselves is ill and takes time off from paid work (or reduces their work), or does so to care for a sick spouse or child, a year including large uninsured medical expenses is likely to be a difficult and costly one for the taxpayer and their household.

II. The Inequitable and Arbitrary Consequences of Current Tax Treatment

A. Medical Expense “Erasure”

As noted above, the 7.5% floor built into § 213 treats medical expenses up to that floor as if they were ordinary consumption-related expenditures (and takes no account of the marginal burden of that percentage expenditure on those lower on the income scale). This produces significant inequity, observable by considering just a few pairwise comparisons between otherwise similarly-situated taxpayers.

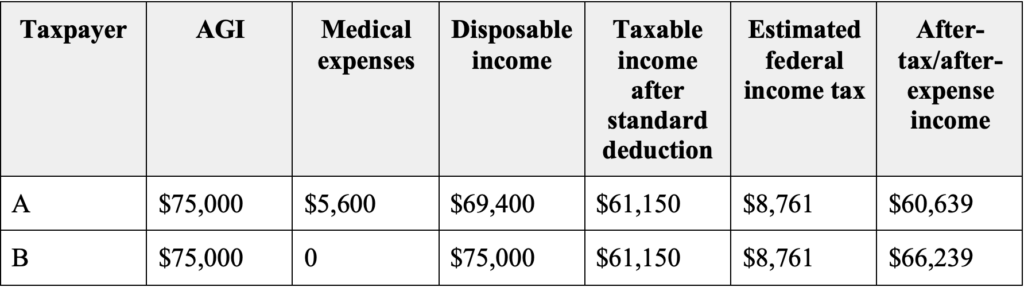

Consider two taxpayers each with an AGI of $75,000. Taxpayer A incurs pre-tax medical expenses of $5,600; Taxpayer B does not. Taxpayer A’s disposable income is reduced to $69,400, before taxes, while Taxpayer B takes home $75,000. Both will owe the same amount of income tax, and both will take the standard deduction—but Taxpayer B has an additional $5,600 in pre-tax income to satisfy their tax obligations, save, invest, or use for consumption. (See Table 3, infra.) Taxpayer B also did not experience the illness, pain, suffering, fear, or distress that gave rise to those expenses.

Table 3. Comparison of Taxpayers With and Without Medical Expenses Below 7.5%

The Code assumes that any given taxpayer will be like Taxpayer A in some years, but like Taxpayer B in most others. Put another way, Taxpayer B is the normative taxpayer around whom the Code is designed. But some taxpayers are Taxpayer A every year. The National Disability Institute has estimated that “a household containing an adult with a disability that limits their ability to work requires, on average, 28 percent more income (or an additional $17,690 a year) to obtain the same standard of living as a similar household without a member with a disability.”37Nanette Goodman et al., The Extra Costs of Living with a Disability in the U.S. — Resetting the Policy Table 1 (2020), https://www.nationaldisabilityinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/extra-costs-living-with-disability-brief.pdf [https://perma.cc/YN3R-5H7P]. Though such an estimate generalizes across a wide variety of situations, it gives at least an approximate sense of the impact of disability on taxpayers’ relative abilities to pay.

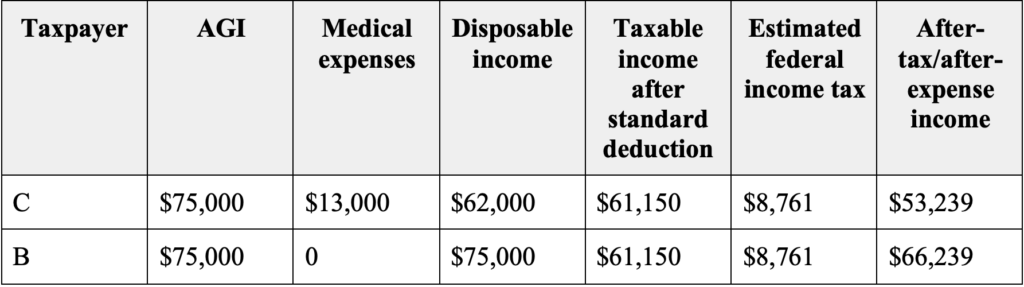

The large standard deduction does not ameliorate this as medical expenses grow larger. Consider again two single taxpayers with that same AGI of $75,000, but in this tax year, Taxpayer C incurs $13,000 in medical expenses—above the 7.5% threshold, but still under the standard deduction. Taxpayer B does not. Again, both will take the standard deduction, and thus owe taxes on $61,150. But Taxpayer C will only have $62,000 to pay those taxes and all other living expenses, while Taxpayer B will have $75,000 to do so. (See Table 4, infra.) While the standard deduction is a tax break for many taxpayers by lopping off more of their taxable income, it discriminates against taxpayers with reduced ability to pay due to significant medical expenses still below the standard deduction.

Table 4. Comparison of Taxpayers With and Without Medical Expenses Below The Standard Deduction

B. Timing Issues

Consider next a taxpayer whose medical situation (or that of a family member) results in them not working at all, or reduces their earnings below the minimum taxable AGI, so that they owe no federal income taxes for that year. This situation is already a crisis for most families, as they consume savings or go into debt—often expensive credit-card debt—to maintain the family and pay the expenses. Even though the medical expenses far exceed the 7.5% floor and the standard deduction, they cannot benefit from the § 213 deduction because there is nothing (or not enough) to deduct them from. And there never will be. This significant financial setback is thus reflected by nothing but one year “off” from paying taxes. If the taxpayer is fortunate enough to have their earnings rebound in the next year, there is still no way to obtain any tax relief based on those prior expenditures. One year off from taxes is not inconsequential, of course, but it hardly takes full account of the economic reality of the situation.

There is a further anomaly here, produced by annual accounting. Heart attacks, cancer and its treatment, a disabling accident or injury, an act of violence with disabling consequences, the organic progression of a congenital condition, the need to care for a seriously ill spouse or child—these events are no respecters of the calendar. And yet, the tax Code discriminates between taxpayers based upon something as arbitrary as the timing of these events.

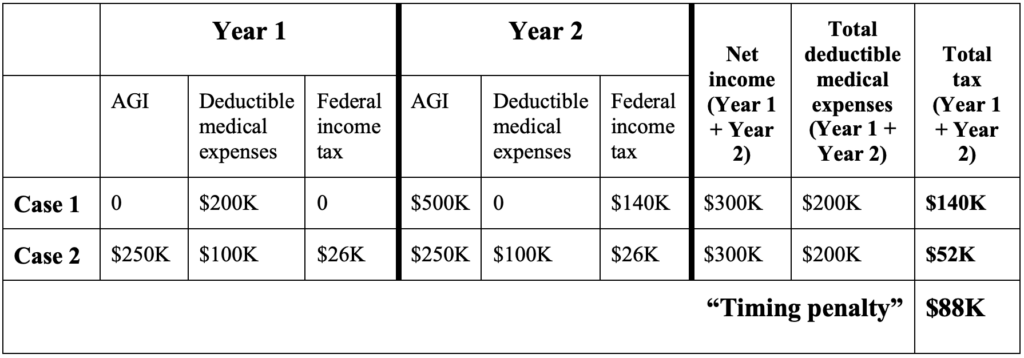

Consider now a taxpayer who has no or very little earnings in Year 1 but incurs medical expenses in that year. If earnings recover in Year 2, the taxpayer pays no tax in Year 1, but is fully taxed at the appropriate marginal rate in Year 2 (case 1). But if the taxpayer works for half of Year 1, when a medical event occurs that precludes resuming work until the second half of Year 2, the taxpayer is taxed in both years, but potentially at a significantly lower marginal rate (case 2). This difference in marginal rates creates significantly less aggregate tax liability in the second scenario, despite total earnings and expenses remaining the same over the two-year period and the same non-earning interval. (For a period as short as two years, the time-value of money can generally be disregarded.)

Table 5. The Timing Penalty

III. “Bending the Tax Clock” for Medical Expenses

The medical expense deduction, with its 7.5% floor and its tax year limitation, coupled with the large standard deduction, generates significant inequity and unfairness. These Code provisions do a poor job of reflecting the economic reality of large-scale medical expenses, and, in effect, mischaracterize them as discretionary consumption expenses. We can and should do better.

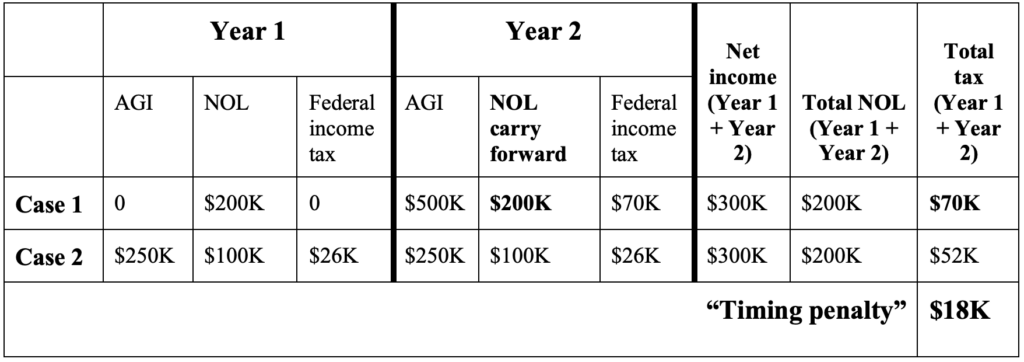

A. Net Operating Losses (§ 172)

To understand how, we can turn to a different part of the Code. Section 172 sets out the tax treatment of what are called “net operating losses” (NOLs).3826 I.R.C. § 172; see also Internal Revenue Serv., Publication 536, Net Operating Losses (NOLs) for Individuals, Estates, and Trusts (2023) [hereinafter Publication 536], https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p536.pdf [https://perma.cc/YK5A-NV92]. As a leading federal income tax law casebook explains, “[T]he objective generally is to identify [a] loss that is traceable to business operations. Thus, in the case of an individual the net operating loss for a year is essentially the excess of one’s trade or business deductions over gross income, including non-business income reduced by certain non-business deductions. . . .”39Lind et al., supra note 4 at 674–75. That net operating loss is deductible, and can be carried forward into future years if it cannot all be “used” in the year incurred. Thus, “Section 172 can properly be regarded as something of a forward-looking income averaging device. While it does nothing to level off income when all the years are profitable years, it does at least permit a loss year to have a leveling effect on later profit years.”40Id. An example may be helpful.

Table 6. § 172

As § 172(b)(2) sets out,

The entire amount of the net operating loss for any taxable year (. . . the ‘loss year’) shall be carried to the earliest of the taxable years to which . . . such loss may be carried. The portion of such loss which shall be carried to each of the other taxable years shall be the excess, if any, of the amount of such loss over the sum of the taxable income for each of the prior taxable years to which such loss may be carried.4126 I.R.C. § 172(b) (emphasis added).

There is no floor, and there is no time limit. Thus, § 172 provides us a model of “a forward-looking income averaging device”42Lind, supra note 4 at 675. that uses “the carryover concept as a kind of departure from strict annual accounting.”43Id. And what’s more, taxpayers taking the NOL deduction are also permitted the standard deduction. The NOL deduction is in addition to, not an alternative to, taking the standard deduction.44Publication 536, supra note 38 at 2, 3, 6. Section 172 is one of several Code sections that demonstrate that the “much-touted integrity of the tax year” is not so very “ineluctable”45Lind, supra note 4 at 645 (“How Ineluctable Is the Integrity of the Tax Year?”). after all: because annual accounting is universally obligatory, carryforward and carryback approaches have been adopted when they better reflect economic reality, fairness, and proper incentives.

Favoring equity and economic reality is the express purpose of this Code section.

The purpose of the net operating loss deduction is to relieve inequities caused by the determination of the income tax based on an annual accounting period. The net operating loss deduction effectively averages a taxpayer’s income and losses over a period of years, thereby reducing the tax disparity that would otherwise exist between businesses with stable incomes and businesses with fluctuating incomes.46How to Calculate Net Operating Loss for Corporations, Bloomberg Tax (Jan. 26, 2024) (emphasis added), https://pro.bloombergtax.com/brief/net-operating-losses/ [https://perma.cc/C75P-9CJZ].

Section 172 does a few things, some of them obvious and some less so. First (particularly when carryback was still permitted), it reflects a commitment to permitting businesses to derive the maximum tax benefit from their expenditures, without regard to revenues or taxable income in the year the expenditure was incurred. Second, it aims to avoid the distortion in business planning that might result if businesses felt that they had to wait to make a large investment until they had enough revenue to offset it, for tax reasons. This is regarded as an undesirable way for the tax law to affect business decision-making, and this provision aims to undo that. Businesses should make those expenditures (even risky ones, that may not pay off) when it makes the best business sense to do so, and what makes business sense is neither reducible to nor exhausted by what makes tax sense.

Just as § 172 helps ensure that business expenses incurred in one year are accurately reflected in overall tax liability both before and after the expenditure, these same justifications apply to large medical expenses. Medical care decisions, including choices of drugs or surgical procedures, often consider both medical and lifestyle realities. The “right” time to schedule a major medical procedure or to begin a course of treatment with an expensive drug should not be affected by its tax consequences. There is no reason for the Code to punish those who make these choices at the “wrong” time in the tax year, or favor those whose timing, wholly fortuitously, is better. If it is appropriate for the Code to encourage a businessperson to take risk in business expenditures by giving her a forward-looking tax benefit if she ends up needing it, surely, the taxpayer incurring large medical expenses is no less deserving of protection.

As currently structured, § 213 produces a “tax disparity . . . between [taxpayers] with stable incomes [and medical expenses] and [taxpayers] with fluctuating incomes [and medical expenses].”47Id. Just as the NOL deduction rules reduce that disparity through the carryover provisions, a medical expense carryover would do the same.

B. The Proposal

Rather than bend disabled bodies and minds to meet the clock, crip time bends the clock to meet disabled bodies and minds.48Kafer, supra note 1 at 27.

Based on the foregoing, I recommend a limited medical expense carryforward provision. This would allow taxpayers to accumulate medical expenses; carry them forward; and deduct them in the first year in which, cumulatively, they exceed the standard deduction (with or without a § 172-style 80% limitation). Should unused expenses remain, the carryforward approach can be continued. A slightly less modest version could include a two-year carryback provision like the one formerly available under § 172, now found at § 172(b)(1)(B) and (C).4926 I.R.C. § 172(b)(1)(B)&(C). Although this adds a degree of complexity to returns, requiring post hoc amendment, it also ameliorates more of the impact of the “loss year” (the high medical expense year).

A carryforward approach (with or without carryback) provides the taxpayer incurring these large medical expenses a dramatic tax benefit. Today, thousands (if not millions) of dollars of medical expenses go undeducted. Whether the taxpayer is taxed as if they had incurred discretionary consumption expenses or escapes taxation because expenses exceed income in the year incurred, the current scheme distorts economic reality. Under this proposal, expenditures whose full tax advantage cannot be utilized in the year incurred, but would be helpful, later, are treated appropriately.

The other benefit of a medical expense carryforward is that it would reflect the taxpayer’s limited ability to “time” their large medical expenses. While a business has some ability to choose when to purchase a new machine or to restock inventory and can take the taxable year into account in doing so, a large medical expense is also often (though not always) unplanned or even an emergency. Thus, the chances that it will carry over into a taxpayer’s ability to earn a living in a subsequent taxable year, rather than “matching” more precisely, is comparatively great.

Even when there is a measure of discretion in the taxpayer’s medical choice (choosing, for example, a more- or less-expensive drug or surgical procedure), cushioning taxpayers from some of the most severe economic consequences of their care certainly makes as much sense as doing the same for a toy store owner who bought too many Pet Rocks or Beanie Babies.50The application of § 172 and NOLs to a toy store merchandise purchase is developed in Lind, supra note 4 at 674–75.

A more radical approach would mirror § 172 even more closely. Recall that a taxpayer eligible for the NOL deduction under §172, including its carryforward provisions, may take this deduction in addition to the standard deduction (the “standard-deduction-plus” model). A prior form included carryback options as well. The most radical approach would thus permit taxpayers with large medical expenses to deduct them in full, with carryforward and carryback as well, in addition to the standard deduction. This would most fully recognize the non-discretionary nature of these expenses, their impact on ability to pay, and would begin to address the foregone-income dimension of disability by reducing taxable income in multiple impacted years, past and future.51Goodman et al., supra note 37 at 2, 11. This is actually how the Code currently treats some disabled taxpayers, though not for such large expenses. Under 26 U.S.C. § 63(f), “Aged or Blind Additional Amounts,” a taxpayer who is blind is entitled to an additional standard deduction of $1,850.5226 I.R.C. § 63(f). A taxpayer may also take this deduction for a blind spouse,5326 I.R.C. § 63(f); Internal Revenue Serv., Tax Topic No. 551, Standard Deduction (2024) [hereinafter Tax Topic No. 551], https://www.irs.gov/taxtopics/tc551 [https://perma.cc/QV93-426S]. There is a further additional standard deduction that may be taken by any taxpayer who is sixty-five by January 1 of the next tax year (that is, taxpayers who turn sixty-five on January 1 of Year 2 may take this deduction in Year 1), and also for a spouse. Whether this is properly understood as a “disability” deduction need not be resolved at this point. in addition to the standard deduction. This long-standing feature of the Code was first added in 1948 and it has persisted despite granting relief for only one type of disability.54Corinne Kirchner & Laura Smith, Legally-Blind Tax Filers, 1983: A Profile, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/83legbltf.pdf [https://perma.cc/7RFD-NXA6]. But these sums are too small to be financially meaningful. A few thousand dollars is only a marginal enhancement of the standard deduction, while medical expenses above the 7.5% floor are frequently nearly as large as the standard deduction itself. Permitting taxpayers to take both the standard deduction and a full medical expense deduction would be a much more radical intervention. It would relieve many taxpayers of any income tax liability at all if their medical expenses plus the standard deduction exceeded their income. It would permit greater overall deductibility because medical expenses over the 7.5% AGI floor would be deducted without regard to the standard deduction. For the same reason, the potential impact on total tax collections is also potentially quite significant.55 Nat’l Academies, Institute of Medicine, Committee on the Consequences of Uninsurance, Hidden Costs, Values Lost: Uninsurance in America 46 (2003), https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/10719/chapter/5#45 [https://perma.cc/9W3S-EPZW] (“The best available estimate of the value of uncompensated health care services provided to persons who lack health insurance for some or all of a year is roughly $35 billion annually, about 2.8 percent of total national spending for personal health care services.”).

The approach recommended here, in either its more modest or more radical form, does not exhaust the possibilities. In 2020, in the context of ameliorating the additional costs of living with a disability, the National Disability Institute (NDI) queried,

- [S]hould individuals with disabilities who meet the ADA definition of disability have a lower [AGI floor for deductibility under § 213] due to the amount of extra costs?

- Should taxpayers with disabilities be allowed to take a deduction for medical or other disability-related expenses in addition to the new higher standard deduction even if they do not itemize?56Goodman et al., supra note 37 at 9.

These tax-related proposals were not fully fleshed-out by the NDI, and unfortunately, they are not very helpful. Giving some taxpayers a different version of § 213, with an eligibility floor of 5% or even 3%, as it was in 1974, would be of almost no effect, given how high the standard deduction is. In addition, importing the ADA— itself an extremely complicated body of law— into the tax Code may only complicate matters.57For example, the ADA protects those “regarded as” having a disability as disabled, for employment anti-discrimination purposes, an amendment that came into being to protect non-symptomatic HIV+ persons from losing their jobs. This proposal may not reach expenses for children, whose disabilities are generally defined by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act,5820 U.S.C. § 1400. not just the ADA.59That is, giving special tax treatment to someone “who meets the ADA definition of disability” may not capture the same group that includes dependents covered by the IDEA definition. See, e.g., Perry Zirkel, An Updated Comprehensive Comparison of the IDEA and Section 504/ADA, 342 Ed. Law Rep. 886 (2017); Jessica Haeffner, Disability Law –– Ninth Circuit Holds Public Schools’ Compliance with IDEA Does Not Automatically Establish Compliance with ADA, 48 Suffolk U. L. Rev. 553 (2015); K.M. ex rel. Bright v. Tustin USD, 725 F.3d 1088 (9th Cir. 2013). The NDI’s second proposal aligns with what I describe as the “radical” approach, but expands it even further, to an as-yet-undefined notion of “disability-related expenses,” with more dramatic fiscal consequences.

The proposal made here charts a middle course between the status quo, which unfairly erases huge medical expenses, and the most radical approaches, which are probably not viable either politically or fiscally. It does so by using a familiar device already in the Code to create more substantive fairness and horizontal equity.

IV. A “Crip Theory” Case for Carryforward/Carryback of Medical Expenses

Thus far, the argument has not depended explicitly on any particular definition of “disability,” or any concepts drawn from disability theory per se. This is intentional. I believe I have made a compelling case for a medical expense carryforward on pure equity grounds. However, this proposal, both substantively and methodologically, can also be grounded in critical disability theory (CDT) (sometimes also called “crip theory,”) and specifically, the innovative, critical treatment of time known as “crip temporality” (or “crip temporalities,” plural). My analysis of § 213 and the recommendations for modifying it also emanate from that larger project, a more sweeping analysis of disability, “crip time,” and normative temporality in the tax Code, and emerge from insights derived from that theoretical approach as well.

The essence of my proposal here involves rejecting what is sometimes called the “ineluctab[ility] of the integrity of the taxable year.” The taxable year is a paradigm case of “normative time.” Normative time structures how we think about the human lifespan, as progress from a period of helpless infancy, through a childhood of developmental “milestones,” through puberty, into young adulthood, maturity, and senescence. Adulthood is the period of maximum strength and capacity, perhaps occasionally interrupted by illness and injury from which one recovers and is entirely restored. Normative time intersects with gender; for most women, reproductive viability winds down sometime around age fifty, but not for men. For all people, aging brings reduced capacity for physical work, along with escalating infirmity and debility. Death follows.

Western industrialized society also largely structures work and education in terms of normative time: the work or school day, “business hours,” the work week, “school nights,” weekends, and vacations. Semesters are numbered and years of school are correspondingly named (1st grade through 12th grade; freshman, sophomore, junior, senior). Legal education and law practice reinscribe this pattern (1L, 2L, 3L; first-year associate, second-year associate, and so on). The background condition of normative time is the mechanical measurement of time itself, through regular unvarying increments: minutes, hours, days, months, years.

None of this is necessary, natural, or neutral. The work of British researcher Poppy Budworth “explores normative time as a disciplinary force in people’s everyday lives.”60Poppy Budworth, Exploded, Broken, Endured: Resisting and Reorienting Normative Time through Feminist Crip Theory, Kings Coll. London: Feminist Persp. Blog (May 11, 2023), https://www.kcl.ac.uk/exploded-broken-endured-resisting-and-reorienting-normative-time-through-feminist-crip-theory [https://perma.cc/TR4H-L6KV]. As Budworth explains, “Linear, expectation-based temporalities are guided by non-disabled and heteronormative principles which reproduce exclusion and difference. As such, normative conceptualisations of time have the potential to disable and marginalise.”61Id. She elaborates, “From exam formats, working patterns, pedestrian crossings at traffic lights, to lifecourse ‘milestones’ such as getting married and having children, conceptualisations of time are dominated by heteronormative and able-bodied/minded narratives.”62Id. Persons who cannot adapt themselves to normative time will struggle in an environment that demands that persons fit themselves to it, and brands those who cannot do so as “disabled.” If compliance with the demands of normative time is not healthy or generative or possible for a person, what then? Children who do not reach “developmental milestones” on time, or who cannot complete schoolwork as quickly as expected, are often understood as disabled on this basis alone. (This is of course not the only way of understanding disability and does not apply to all disabilities.) In some cases, a mismatch with normative time is one aspect of a disability; in other cases, challenges of complying with normative time may be a social consequence but not otherwise an inherent feature of the disability.

Taken together, these mostly unnoticed aspects of normative time are part of our current épistémè. Michel Foucault introduced this concept in his 1966 book, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences.63Michel Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (R.D. Laing ed., Pantheon Books 1970) (1966). Rather than offering a concise definition, however, Foucault defines it inductively both here and in his 1969 book, The Archaeology of Knowledge.64Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge (A.M. Sheridan Smith trans., Pantheon Books 1972) (1969). An épistémè is “the total set of relations that unite, at a given period, the discursive practices that give rise to epistemological figures, sciences, and possibly formalized systems.”65Paulo Pirozelli, The Grounds of Knowledge: A Comparison Between Kuhn’s Paradigms and Foucault’s Epistemes, 62 Kriterion 277, 280 (2021) (referencing Foucault, supra note 63 at 191). We might paraphrase this as meaning that an épistémè brings together what can be said and thought coherently and intelligibly, thus what is and is not a form of knowledge, recognized in a particular place and time.

The idea of the épistémè historicizes the idea of what it is possible to know, what statements can be recognized as knowledge in a particular place and time, rather than treating this as something universal and timeless. Foucault builds on the Kantian notion of a priori categories of understanding and forms of sensibility (of which time is one),66Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason 74 (Norman Kemp Smith trans., St. Martin’s Press 1965) (1781). but argues that these are not fixed and eternal. While initially Foucault asserted that “In any given culture and at any given moment, there is always only one épistémè that defines the conditions of possibility of all knowledge,”67Foucault, The Order of Things, supra note 63 at 168. in his later writings, he allowed also for the possibility of contesting épistémès, reflecting the relationship between power and knowledge in a particular place and time.68The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality 55 (Graham Burchell, Colin Gordon & Peter Miller eds.) (1991).

A dispute inside our épistémè with its notions of normative time is one that relies on the same assumptions rather than challenging or contesting it. An example would be a dispute about who is entitled to extended time for exams or assignments in the educational setting, or about exactly how much “extra” time they should be given. Such disputes rarely question the fundamental assumption (the norm) that performance under time limitation is an appropriate way to measure learning, or the norm of fairness that assumes that all students must take uniform exams. Similarly, larger-scale arguments about whether “reasonable accommodations” or Equal Protection is the appropriate framework for addressing disability discrimination through law is happening inside a shared épistémè. Both sides are operating within a shared set of assumptions about normative time, and what to do about (some) disabled persons’ apparent inability to comply with it, namely, to provide accommodations through various legal devices. Neither side of these disputes is engaged in any critique of normative time itself, as applied to all learners or workers, or to ideas about what education is, or what valuable or productive work is.

Radical crip theory mobilizes that level of critique. It challenges the role of normative time in the dominant épistémè itself. We can see an analogy in feminist and race-critical epistemologies compared to the anti-discrimination approaches that preceded them. In the 1970s, as part of the development of feminism and gender studies more generally, Robin West and other philosophers began to explore how women’s distinctive forms of knowing and knowledge were marginalized or excluded from allegedly or apparently neutral analyses of the very conditions of knowledge itself.69See, e.g., Feminist Epistemologies (Linda Alcoff & Elizabeth Potter eds., 1993). For some feminists, this was the result of essential gender or sex differences between men and women; for others, it was a product of systemic sexism and oppression on the basis of sex/gender. For intersectional Black feminists, this had a racial dimension as well. As Ntozake Shange famously expressed it, “but bein alive & bein a woman & being colored is a metaphysical dilemma.”70Ntozake Shange, for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf 47 (1975). What Shange states poetically is a tension felt by those both inside the épistémè of their time, simply by virtue of “bein’ alive” in it, while also being subordinated and marginalized within that scheme, not only politically or socially, but metaphysically or epistemologically, unable to express or find acknowledgement of one’s own ways of being and knowing.

Critical race feminism helped uncover the non-neutrality of the subject position of the White man, the position from which knowledge (including legal knowledge) had invisibly emanated.71See, e.g., Kimberlé Crenshaw, Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics, 1989 Univ. Chi. Legal F. 139 (1989), https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1052&context=uclf [https://perma.cc/ZDZ4-Z7AC]; Angela Harris, Race and Essentialism in Feminist Legal Theory, 42 Stan. L. Rev. 581 (1990). It simultaneously demonstrated how apparently neutral understandings of the person or citizen in fact embedded race and sex/gender (and specifically, typically, White race and male sex/gender), and how feminism so often meant White feminism.72Id.

Similarly, critical disability theory first adds the idea that disability itself is an intersectional and political identity and status that analyses of inequality and discrimination must take into account. Race- and gender-based norms also implicitly include and rely upon ideas of able-bodiedness/able-mindedness that exclude, marginalize, and devalue many people. At this level, disability theory simply adds another identity category of which the law variably takes account. On this approach, “ableism” is just another “-ism” (such as racism or sexism), that must be purged in the liberal-legal quest for equality or neutrality.

The more radical notion of “crip time” does something much more profound, by problematizing the notion of normative time itself, in theorizing it, and interrogating it as a site or technology of harm. It does not simply add (yet another) “category” on the basis of which individuals might experience discrimination, marginalization, or subordination. It calls into question much more fundamental structures of how we understand being a human being who lives in time. The dominant post-industrial épistémè in which we operate blurs the distinction between existing in time, as we all must do, and operating under the extremely rigid constraints of uniform intersubjective temporality. The temporality of our épistémè values speed and stigmatizes slowness and lateness. It understands productivity in assembly-line quantitative terms. It disregards the rhythms of nature and the seasons, by providing everything from year-round tomatoes to air-conditioning and indoor ice-skating rinks. We make our own seasons.

The arbitrariness and unfairness of a great deal of race- and sex/gender-based discrimination is now much clearer than in times past, even when those structures are tenacious and resistant to change. The ways in which normative time itself operates to rationalize, naturalize, obscure, and erase disability discrimination and to create and marginalize a class of disabled people are much less well understood. This reform proposal, despite its technical nature, is an opportunity to surface not only certain deep injustices perpetuated against some of our fellow citizens and taxpayers but also the role played by normative time in our thinking about the law generally, and tax law specifically. The role played by time in tax law makes is a surprisingly fruitful site for this excavation.